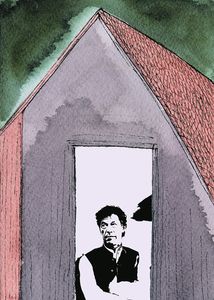

Imran Khan shunned the palatial prime minister’s house in Islamabad with its 524 servants, and moved into a three bedroom house. He has retained just two servants. The cricket star, who was once a luxury icon, has now sworn to an austere life. He has also instructed that when he travels within the country, he would like to stay in government guest houses, and avoid the palatial mansions of the state governors or the retreat built for the country’s rulers in the hill station of Murree. Khan also wants to convert the prime minister’s house into a hospital or a research centre. This is in tune with his aim of creating a “new Pakistan”, where corruption would be banished.

Khan’s decision has led to calls in India that the rulers should abandon lavish lifestyles. There are examples of the former Tripura chief minister Nripen Chakraborty, who donated most of his salary to the CPI(M) and lived with just one suitcase. There are also memories of A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who lived in the world’s lagest presidential palace, and yet paid for the stay and food of his relatives when they visited him at the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

The only president who expressed a desire not to live in the Rashtrapati Bhavan was Neelam Sanjiva Reddy in 1977. He wanted to stay in a four room bungalow allotted to ministers, but prime minister Morarji Desai and home minister Charan Singh convinced Reddy that because of ceremonial and protocol purposes, the president should live in the palace with 300 rooms.

But, senior officials dealing with high dignitaries have used persuasive arguments to convince the holders of high offices that simple living can be costly, too. When Vice President Venkaiah Naidu said he preferred to travel by commercial flights, the security mandarins pointed out that it would be equally costly because the security detail of 24 guards will have to travel on the same plane.

Like the prime minister of Pakistan, his Indian counterpart, too, faces several security threats. After the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984, the government decided that the prime minister would live in a designated housing complex and the special protection group (SPG) was created. Initially, three bungalows spread over 15 acres were used by the prime minister. Now, six bungalows on Lok Kalyan Marg, spread over 30 acres, have been taken over, with the additional bungalows being used for security purposes. Senior officials in the cabinet secretariat said there was no question of scaling down the size in view of security urgencies.

But, there is a need to cut down expenses on the residences of prime ministers and chief ministers. The Rashtrapati Bhavan has seen big expenditure on facilities for its officers and staff, and several Raj Bhavans have several hundreds of employees serving one master. The new residential complex for the chief minister in Hyderabad cost Rs100 crore. Uttarkhand Chief Minister Trivendra Singh Rawat announced that he would only use four rooms in the 20 room chief ministerial residence. Tamil Nadu’s chief ministers M. Karunanidhi and J. Jayalalithaa used their personal residences while in office, but both their houses were expanded and maintained at state expense.

In some states, huge bungalows are given to ex-chief ministers. While the Supreme Court ordered ex-CMs of Uttar Pradesh to vacate their homes, Madhya Pradesh continues to humour its former rulers. In the Centre, only former presidents, vice presidents and prime ministers get the facility of government bungalows. Imran’s example will be a hard act to follow in India, given the compulsions of security, ceremony and protocol, as well as precedents set during imperial and democratic eras.

sachi@theweek.in