Sanjay Mitra, the defence secretary, is navigating the minefields spawned by the standoff between the United States and Russia, as well as the buffeting winds of the Rafale controversy. It is a big load he carries as India negotiates with the US for a waiver on sanctions imposed on countries which buy sophisticated arms from the Kremlin. India is buying S-400 missiles from Russia, which can knock out US-made F-35 fighter jets. Mitra is preparing for the first ever two-plus-two dialogue, where defence and external affairs ministers of India and the US will work for higher strategic embrace.

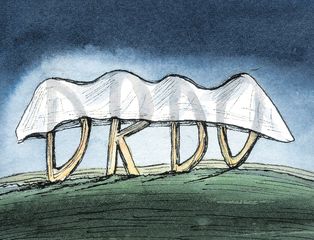

But, now, Mitra has another big burden. He has been given additional charge of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) after Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not give a second extension to S. Christopher. The latter had been given the job in 2014, replacing the UPA appointed Avinash Chander. Even though Christopher was on a year’s extension, the government could not make up its mind on the long-term leadership of the country’s top defence research organisation. While a panel of names has been put up by key bureaucrats like Nripendra Misra, principal secretary to prime minister, and P.K. Sinha, cabinet secretary, the political leadership is yet to take a call.

The government has also been reluctant to entrust the job to any internal candidates in DRDO, like scientific adviser to defence minister Sathish Reddy, Brahmos chief Sudhir Mishra or DRDO’s electronics and communication systems head J. Manjula. If chosen, Manjula would be the first woman to head any one of the trinity of strategic research organisations—atomic energy, space and defence research.

The delay has led to speculation that the government may bring an outsider to head the country’s defence laboratories which have developed critical products like Tejas fighter planes and Arjun battle tanks.

Modi who prides himself on being decisive, in comparison to his predecessor Manmohan Singh, has, however, been late in filling some key vacancies in the government, allowing short periods of adhocracy, especially in tribunals. On some occasions he seems to follow the dictum of another predecessor, P.V. Narasimha Rao, who had famously said: “Not taking a decision is also a decision.” Modi had downgraded the importance of the head of research by taking away the role of adviser to defence minister, which had been enjoyed by several heads of DRDO, most famous of whom was A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. There were occasions when Kalam’s advice mattered more to prime ministers than those of generals.

DRDO itself is facing a crisis of redefining its own charter and character after the Modi government opened up defence production for the private sector. There are strong lobbies which are arguing that some of the research work being done by the DRDO can now be done by private organisations. Also, private manufacturers can take copyright of products developed in foreign countries and approved by the armed forces, thereby reducing the footprint of the DRDO.

Another sword hanging over the organisation is the report of Vivek Rae Committee on defence procurement, which recommends the creation of a new procurement body for armed forces, eliminating the veto power of DRDO for indigenous development. Rae’s report had created angst in DRDO that it favoured the model adopted by France for defence procurement. But, strong resistance from Army, Navy and Air Force has delayed adoption of the Rae report. If the selection process produces a man or woman of Kalam’s calibre, the delay would be justified.

sachi@theweek.in