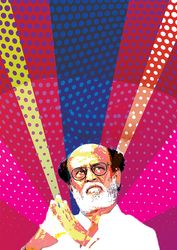

One has heard of adolescents plucking the petals of a daisy muttering, “she/he loves me… she/he loves me not”, but the spectacle of an ageing cine star of yore doing the same as he puts his toes into political waters only to pull them out has gone on for so long as to have lost all credibility. For the nth time, Rajinikanth has indicated that he is going to take the plunge as the new year begins. It has not stirred the excitement that followed his first announcement of throwing his hat into the political ring. Is this another feint? Is this for real? Does it really matter? The latter, I think, is the real question.

My north Indian friends are generally bewildered at Tamil Nadu politics. What, they wonder, has the cinema to do with politics? That is the question most germane to Rajini’s latest intimation of entering the political fray, the launch pad being the Tamil Nadu assembly polls due in May 2020.

Counter-intuitively, the fact is that being a film star has little to do with success in politics, whether north or south. North Indian stars like Amitabh Bachchan, Rajesh Khanna, Shatrughan Sinha and Sunil Dutt are evidence for this; strangely, it is Tami Nadu that provides the most telling proof. For some of the greatest stars of the silver screen in Tamil Nadu have come a cropper in politics even if their initial entry generated a measure of frisson—Sivaji Ganesan, Vijayakanth, Kamal Haasan. Contrariwise, C.N. Annadurai (“Anna”) and M. Karunanidhi and, later, MGR were radical social reformers who used cinema as a medium for the propagation of their social and political views.

All three started their careers in repertory theatre on the stage and only slowly turned to cinema. They complemented each other. Anna was the scriptwriter; Karunanidhi, the dialogue master; MGR, the brilliant actor. They used cinema as an innovative new medium for political messaging, just as social media is now being used for political purposes. And, just as social media arrived at the time an alternative idea of India was to be propagated, the Dravidian movement used cinema to demand a new social order to challenge Brahmin dominance, and the religious superstitions, rites and rituals on which this pre-eminence was based. They added “self-respect” weddings, widow remarriage, opposition to untouchability and abolition of zamindari system to their platform and highlighted the ancient Tamil language and Tamil culture, with Anna, in particular promoting a Tamil that was “close to the formal language and void of Sanskrit influence”.

Thus Nalla Thambi (Good Brother) and Velaikari (Servant Maid), plays scripted by Anna, were turned into box-office hits in 1948 and 1949, sharply attacking oppression by the rich of the poor and denigrating idol worship. Parashakti in 1952 built on this with its pungent critique of Brahmins and Hindu religious customs. Around this time, the Dravidian message started breaking its urban confines and spreading to rural Tamil Nadu largely because the supply of electricity to rural areas facilitated the spread of cinema theatres to rural towns.

Other hit films followed, with MGR lending his rich thespian talents to taking the rebellious, revolutionary message to the masses through such films as Nadodi Mannan (Vagabond King, 1958) and Adimai Penn (Slave Girl, 1969) to, in MGR’s words, “fight against evil and support the good”. J. Jayalalithaa, with over 140 films, many opposite MGR, was in the political anteroom absorbing and subtly altering this messaging.

This is a very abbreviated account of how the Dravidian movement forged a nexus between their politics and the cinema. Compared with them, Rajini has only twiddled a cigarette in his fingers to establish a cult fan following.

Aiyar is a former Union minister and social commentator.