INDIA’S DEMOGRAPHICS have always been a mindboggling number soup. Almost everything to do with people here is on an unimaginable scale. Whether it is the general election, the mid-day meal scheme, or even the ongoing lockdown, the exercises end up being the largest in the world.

India is now beginning to bring its citizens back from across the world, and the sheer scale of the operation is jaw-dropping. There are 1.4 crore Indian nationals abroad, in every continent and almost every country, and many of them now want to return home. Over five lakh NRIs have registered for evacuation from the Gulf region alone.

The global spread of Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdowns resulted in lakhs of Indians getting stranded abroad. Among them were those who lost their jobs, and tourists and students whose money was fast running out.

But India, having sealed itself from the outside world, was just coming to grips with the situation within its borders. The displacement of migrant labourers itself was an overwhelming problem. All that the country could tell its nationals abroad was to hold on a little longer, and approach the local missions for help. The advice, however, only agitated the stranded, as they read reports of foreigners being evacuated from India. “Why couldn’t we have been put onto the flights which were going to India to evacuate foreigners?” asked a group of stranded Indians in Malaysia. “If it had to be a paid return, we would have returned weeks ago.”

What has gone unreported, though, is the planning of massive backend operations to accommodate the returnees. Tying up with state governments to arrange quarantine facilities for the lakhs of returnees, managing the domestic leg of the return, and acquiring enough testing kits to ensure that the returnees do not affect the infection curve—all this took time. Logistics planning is complex at the best of times, and it certainly is not business as usual right now.

When India evacuated the first set of nationals from Wuhan in February, it took only 48 hours to establish a standard operating procedure and have the Army and the Indo-Tibetan Border Police set up a quarantine facility. Today, as many of the first responders are themselves ill, the ITBP is using its facility for its own personnel.

The ministry of external affairs is the nodal ministry for the evacuations. It has expanded its team in the Covid-19 management cell, and has posted senior officers to coordinate developments in every state.

Another big task was to establish screening of evacuees. The UAE, the only nation that has told other countries to take back their citizens, is offering to test all passengers. From other countries, however, only “asymptomatic travellers” will be allowed to return to India. This is a huge risk, since asymptomatic persons can also spread Covid-19. But, given the constraints, this remains the best option.

When the government finally announced that it would start bringing back people, the stranded finally saw hope. The homecoming, however, is not turning out to be the sweet Bollywood dream many had expected.

India had launched massive exercises to repatriate nationals earlier. The three big evacuations were in 1991, when Iraq invaded Kuwait; in 2011-12, during the Syria-Libya crisis; and in 2014-15, during the Iraq-Libya crisis. The 1991 evacuation won Air India the Guinness record for the maximum number of evacuations—1.9 lakh. The 2014-15 evacuation was the first time a Union minister (V.K. Singh, minister of state for external affairs then) camped on site to oversee operations.

“They all had their challenges,” recalled Shashank, former foreign secretary who was in charge of arranging documents for the evacuees during the Kuwait crisis. “But this time, the situation is totally different. It is an open-ended evacuation, from across the world, unlike the limited-point evacuations of the past. The evacuees aren’t necessarily returning to a safer place; the virus is everywhere. In that sense, people can exercise more choice on whether they want to return or not.”

The positive side, according to K.P. Fabian, who was joint secretary of the Gulf division in the external affairs ministry, is that the Kuwait evacuation was carried out before the time of emails and smartphones.

Civil Aviation Minister Hardeep Puri said the government’s finances were under strain. The aviation sector is gasping, even with the recent injection of subsidies. Taxpayer money cannot be spent on free rides home. So, for the first time, evacuees are being told to pay their fare, and adhere to a 14-day institutional quarantine.

“We have tried the most competitive prices commercially, tying up with hotels to quarantine people,” said an official. Yet, the proposed bill has come as a rude shock for the stranded. “We are asked to keep aside around 070,000 for the return and quarantine. If we had that much money, wouldn’t it be better to stay back for now?” asked B. Satyadeep, a software engineer from Odisha who lost his job in Kuala Lumpur.

The government’s decision on fares has made many people weigh their options. Sources said many people who had registered for evacuation were dropping out. “The government needs to work with Indian communities abroad and host governments to ensure that many of the people can remain there,” said Shashank. “Their stay could be subsidised till they get new jobs.”

This effort is already afoot, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla holding talks with their counterparts abroad. India is working hard on its Gulf diplomacy, sending gifts and consignments of medicines, ensuring uninterrupted food supply during Ramadan, and tapping the goodwill that Modi has personally earned over the past five years. India has even sent a rapid response team to help Kuwait. But it has not helped that the countries are themselves strained by the pandemic, and that there is growing discontent among them over India’s alleged Islamophobia.

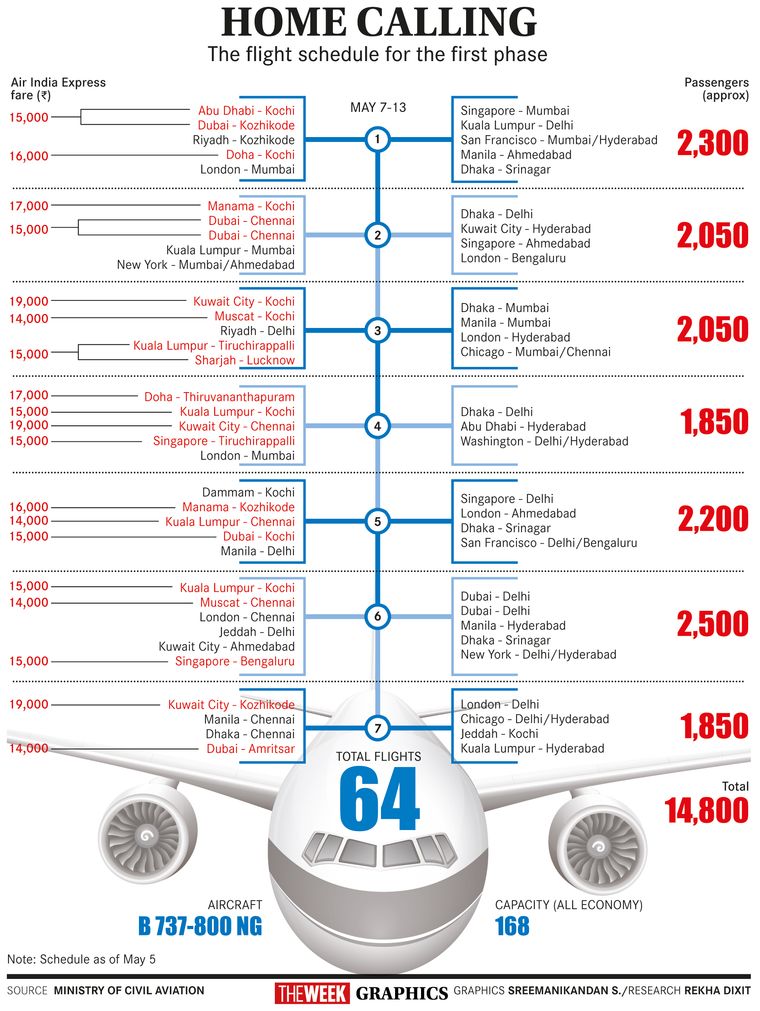

With social distancing norms reducing the already limited capacity of each flight, the government is sorting the candidates according to a list of the most “compelling reasons” for evacuation. The list gives priority to those facing deportation, those who have lost jobs, short-term visa holders, those who are ill or pregnant, the elderly, those who have had a death in the family, and tourists and students. The measures to protect the crew and passengers have compounded the expenses.

The first set of 64 flights is heading to 12 countries to bring back 14,800 Indians. Government sources say NRIs, overseas citizens of India, green card holders and foreign nationals could be accommodated on onward flights, if host nations are willing to accept them. Puri, however, said the first flights were flying out empty. As the lockdown is eased, systems could be smoothed out and onward flights could be utilised, too.

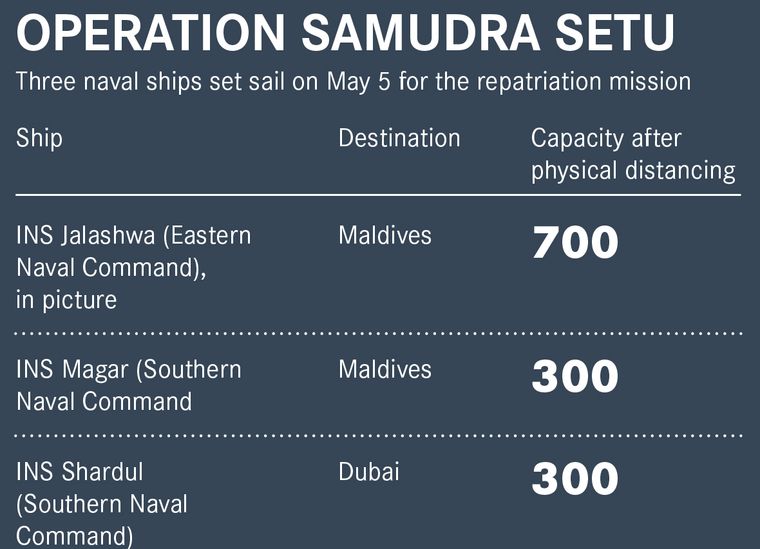

Apart from the Air India flights, the Indian Navy is also dispatching its ships under Operation Samudra Setu—INS Jalashwa and INS Magar to the Maldives, and INS Shardul to the Persian Gulf. The mode of payment for naval evacuation is still unclear, but it is certain that the voyage will not be fun. Cyclonic activity has already started in the Indian Ocean and the waters are choppy. Sources said onboard medical facilities were basic. The Air Force is on standby, too.

In later phases, Indians have to be brought home overland from Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan. Since a large chunk of the reverse migration comprises people who have lost jobs, the government is identifying their skills to prepare a database and absorb them into flagship projects. But it is easier said than done, given the economic gloom and job losses in India. According to Fabian, even though the states are responsible for the rehabilitation of workers, they need funding from the Centre.

One day, India might look back at this evacuation mission as yet another record-breaking achievement. For now, though, it cannot rest on its past laurels. So, armed with masks and gloves, the country is preparing to welcome its returning citizens.

WITH NAMRATA BIJI AHUJA AND PRADIP R. SAGAR