In 2016, when the Aadhaar Act was passed, the government hailed it as a revolution—one identity number to unlock everything from welfare subsidies to mobile connections. But the celebration quickly gave way to courtroom drama. Petitions flooded the Supreme Court, questioning the scheme’s impact on privacy and personal liberty. For two years, Aadhaar was less a policy in action than a policy on trial. Finally, in 2018, the court upheld its core but struck down several key provisions. What was meant to be a showcase of state capacity ended up as a legal marathon, leaving citizens and the government unsure of its boundaries.

Aadhaar’s story is not an outlier; the farm laws of 2020 followed a similar arc. Pushed through Parliament in record speed, they aimed to overhaul India’s agricultural economy, but ended up sparking street protests and legal challenges. Questions about federal powers, farmers’ rights, and market regulation remained unresolved as the government, under immense pressure, repealed the laws barely a year later. Once again, a grand legislative vision collapsed under the combined weight of political anger and constitutional vulnerability.

Such episodes expose a deep flaw—laws are often created on shaky legal ground in India. Drafted in haste and pushed through Parliament with minimal scrutiny, they unravel when challenged in court. The cost is heavy. Governments lose credibility, citizens lose clarity and courts lose years that could be spent on other pressing matters.

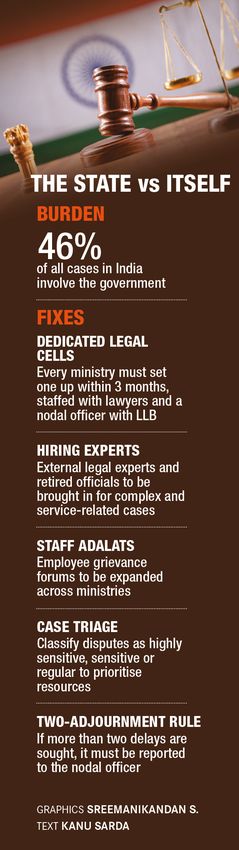

The numbers show just how deep the problem runs. Nearly half of all litigation in India involves the government itself. And much of this is not about sweeping constitutional questions, but about avoidable disputes—pension claims, service transfers, tax appeals and contradictory circulars issued by different ministries. The state is not just the biggest lawmaker, it is also the country’s biggest litigant.

Now, the government wants to break this cycle. As part of its National Litigation Policy Plan, it is considering a new filter—the litigation risk assessment. The idea is simple but radical: before a law even leaves the drafting table, it must undergo a kind of legal stress test. Just as a factory project needs environmental clearance before breaking ground, every proposed law or major policy would be screened for constitutional risks, drafting ambiguities and rights conflicts. If Aadhaar had been through such a process, its privacy concerns might have been flagged early, sparing years of legal wrangling. If the farm laws had been tested, their vulnerabilities could have been addressed before they reached the floor of Parliament.

The reform does not stop at new laws. The government is also overhauling how it fights the mountain of existing cases. Ministries will no longer be allowed to treat litigation as a clerical afterthought. Every department will have dedicated legal cells, staffed by trained lawyers and headed by senior officers. For complex constitutional or commercial disputes, ministries can hire external experts rather than leaving everything to standing counsel. Routine service disputes, which form the bulk of government cases, are to be handled more proactively through grievance redressal forums. The department of posts has already shown what is possible with its “staff adalats”, where employee complaints are settled before they snowball into lawsuits. Other ministries are now expected to follow the lead.

Take the case of a retired postal worker in Delhi. All he wanted was the dignity of a timely pension. Instead, he found himself waiting—month after month, year after year, for arrears that never arrived. His file had already inched its way towards the Central Administrative Tribunal, another long legal battle looming over his twilight years.

Then, a staff adalat brought big relief. What could have dragged on for years in court was settled in weeks. His dues were released, and with them, the quiet relief of knowing he would not have to fight anymore.

Even the culture of delay, long associated with government litigation, is being targeted. Judges often complain of state lawyers appearing unprepared, seeking adjournment after adjournment. Under the new policy, if a ministry seeks more than two consecutive adjournments, the reason must be reported to a nodal officer.

The government’s litigation management directive spells out how this would work. Ministries drafting new legislation would be required to map the legal landscape around it, review relevant case law, and assess where disputes might arise. Each proposal would be graded in terms of litigation risk—high, medium, or low, along with an estimation of possible costs if challenges materialise. Ministries would also have to draw up a mitigation plan, suggesting clearer drafting, tighter definitions, or grievance mechanisms to pre-empt disputes. India would be joining the UK, where ministers must certify that laws comply with the Human Rights Act, or the US, where the department of justice reviews draft legislation for constitutional soundness.

Senior advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan called it a long overdue reform. “Most of the avoidable litigation we see is not about high principle but about sloppy drafting and conflicting notifications,” he said. “If ministries are forced to run their proposals through a structured legal filter, it will save the courts years of needless burden. But the danger is that it should not become a cosmetic exercise, where risks are papered over rather than addressed.”

A senior law ministry official told THE WEEK that the government had been clogging courts not out of necessity but negligence. “Cases were filed mindlessly, appeals became a reflex. If [the reform] is followed in spirit, the state can move from being India’s biggest litigant to a model of legal discipline.”

If done in earnest, these reforms could change the way India makes and fights its laws. New statutes would be sharper, sturdier and far less likely to unravel in court. Citizens and businesses would gain the certainty they crave. The exchequer would save crores by avoiding pointless appeals and penalties.

Whether these reforms succeed will depend on political will and bureaucratic discipline. But the intent marks a shift. Instead of relying on courts to clean up after hurried lawmaking, the government is trying to build foresight into the process.

The bigger challenge lies in practice. Parliament has grown used to rushing bills through, often with little debate or committee scrutiny, leaving courts to do the hard constitutional filtering. Aadhaar and the farm laws are reminders of the price of such haste.