Courts in India, especially the Supreme Court and High Courts, have a vital role to play, not only in adjudicating disputes but also in protecting the rights of citizens. India is one of the few countries where the right to approach the highest court for enforcement of fundamental rights is in itself a fundamental right.

It is not as if there were no remedies similar to writs prior to the framing of the Constitution. Remedy in the nature of habeas corpus was available under criminal law, and any officer could be compelled to do his duty enjoined under the Specific Relief Act, similar to a writ of mandamus. These were, however, statutory rights, and as noted by Dr B.R. Ambedkar in his Constituent Assembly speech on December 9, 1948, they could be taken away at any time. Therefore, the Constitution has vested very wide powers upon the superior courts under Articles 32 and 226.

Under the Constitution, there is separation of powers among the three wings. The judiciary is, however, vested with the power to ensure that any action, legislative or executive, falls within the ambit of the Constitution, and if the rights of a citizen are taken away, then that citizen can approach the court for enforcement of his rights.

In the recent past, views have been expressed that the superior courts have not diligently discharged their Constitutional functions. The courts have two main functions: i) adjudicatory function; and ii) guardian of the people. As far as the first is concerned, other than long delays, one could say that the courts have effectively discharged their functions. However, with respect to protecting human rights, I do feel that some courts have fallen short of what is expected of them.

Looking back at the last couple of years, many High Courts have done a commendable job in discharging their function as the guardian of the people. Justice Govind Mathur as chief justice of the Allahabad High Court led from the front and took a number of decisions that highlighted the role of the High Court as a protector of rights and enhanced its image and stature.

Whenever actions of the state violated the fundamental rights of the citizens, the Allahabad High Court rose to the occasion and did not hesitate to take the bull by the horns. One of these decisions is the case involving the Uttar Pradesh government putting up posters with details of protesters of the Citizenship Amendment Act for damaging public property. The court took suo moto cognisance and held it to be an “unwarranted interference in privacy of the people”.

Many High Courts have worked tirelessly even during the pandemic. Significant decisions, too many to be enumerated, were rendered by the Bombay, Madras and Karnataka High Courts, where the chief justices led from the front to protect the rights of the citizens.

The Delhi High Court granted bail to persons arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for their participation in the anti-CAA protests. It firmly dealt with issues related to Covid-19, including shortage of oxygen in Delhi. The Kerala High Court granted anticipatory bail to a filmmaker in a sedition case filed against her for her remarks criticising the government’s action in Lakshadweep. The Patna High Court came down heavily on the state government for its reluctance to put in public domain the number of Covid-19 deaths.

The Tripura High Court effectively monitored the distribution of vaccines. The Jammu and Kashmir High Court directed the government to explain what steps it was taking to vaccinate disabled people. The Manipur High Court directed the state to ensure adequate ICU beds and other medical facilities in remote areas. The High Courts would have done an even better job if the retirement age of High Court Judges was the same as that of Supreme Court judges and there was no mad scramble to reach the highest court.

However, as far as the apex court is concerned, it has been a mixed bag. There have been orders upholding the rights of citizens like in Arnab Goswami’s case and Vinod Dua’s case, but in some equally important cases, either the petitioner was asked to go to the High Court or orders were not passed for a long time.

In cases relating to Jammu and Kashmir—be it the challenge to the abrogation of Article 370, or the challenge to the detention of political leaders—the Supreme Court by not deciding the issues did not enhance its stature. These were extremely important matters, which should have been decided expeditiously. If the Supreme Court could decide important issues like Maratha reservation and some not-so-urgent cases like Prashant Bhushan’s contempt case, I see no reason why extremely important issues relating to Jammu and Kashmir could not be decided.

Habeas corpus petitions are always treated as extremely urgent and normally get precedence over all other matters. Almost all habeas corpus petitions from Jammu and Kashmir were disposed of as infructuous after the government released the leaders. I feel that just as Justices S. Rangarajan and Rajendra Nath Aggarwal of the Delhi High Court decided a petition even after release of the detenu in the Bharti Nayar case (1972), the apex court, too, should have decided whether the detention of these political leaders was legal or not. Every citizen who is detained even for a day has the right to know whether his detention was lawful.

The manner in which the apex court dealt with cases of detention of persons under laws like the UAPA was also not proper. The bail applications were either rejected or kept pending for a long time. Even if the bail applications were rightly rejected, it was the duty of the court to ensure that the trial was concluded at the earliest. This was not done. Resultantly, some citizens have been incarcerated for many years and the trials are nowhere near beginning, what to talk of conclusion.

Another area where in my view the apex court could have done better was in cases relating to the rights of citizens who had been forced to migrate from cities when the first lockdown was announced in March 2020. In the beginning, the courts may have been right to not interfere, because the executive assured the court that it was taking care of the migrants. However, when soon it was apparent that the statements being made on behalf of the Union, that all is well, were not correct, the court should have played a much more active role in ensuring that these poor citizens were not denied their fundamental rights. On the other hand, many High Courts took up the cause of the migrant workers and did a creditable job in protecting their rights during the first lockdown. Even during the second wave of the pandemic, various High Courts actively monitored the situation related to shortage of essential supplies, virtually forcing the Supreme Court to intervene.

It is the duty of the apex court and the High Courts to intervene when it is brought to their notice that fundamental rights of citizens have been violated. A little bit of friction between the judiciary and the executive or the legislature is always welcome, because that shows that the courts are actually doing their job.

But all is not lost and there is more than a glimmer of hope. In the recent past, there have been some notable actions taken by the Supreme Court, which reinforce our faith in the courts. One of these is the non-judicial but extremely fair and independent action of the Chief Justice of India in the matter of selection of the CBI director. Another is the manner in which the Supreme Court dealt with matters relating to the second wave of the pandemic. It clearly spelt out that it meant business and was not cowed down by the aggressive stance of the government. What gives me great hope is the strong message sent out by the CJI in his recent P.D. Desai Memorial Lecture, where he voiced his strong support for the ‘rule of law’ and the importance of dissent in democracy.

In any court, there are bound to be differences of opinion among judges, which is always welcome. It would be a sad day if all the judges always took the same view, liberal or conservative. There has to be a balance between both the views and I see no problem in this because as judges we take an oath to uphold the Constitution and the laws. The only Gita, the only Quran, the only Guru Granth Sahib, the only Bible and the only Zend-Avesta for judges is the Constitution of India. Judges cannot have any religious, political or social agenda, and they must remain true to their oath and diligently perform their duty of upholding the Constitution without fear or favour, affection or ill will.

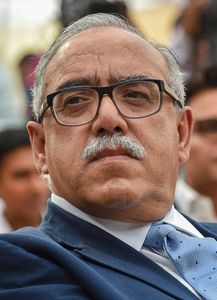

Justice Gupta is a former Supreme Court judge.