His heart skipped a beat when he saw a young, masked gunman in military fatigues walking out from behind the stand of tamarind trees. He later told me that it was not out of fear or anxiety. He just realised that the crucial moment had finally arrived.

“Who is Telam Boraiya?” asked the young man.

“That would be me,” replied Boraiya, 71, the Bijapur district president of Gondwana Samaj, a prominent tribal organisation in Chhattisgarh. He was sitting on a charpoy surrounded by a growing throng of villagers, at the Tummel settlement in Sukma district.

It was April 8, five days after Maoists ambushed a joint team of the 210th Commando Battalion for Resolute Action (CoBRA) and the Bastariya Battalion of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and the District Reserve Group and the Special Task Force of the Chhattisgarh Police, and killed 22 jawans. Tummel is barely 10km from the ambush site that lies between Jonaguda and Tekulguda villages in Sukma district.

“Come with me, the commanders want to talk to you,” the young man said. Boraiya agreed, but he insisted that Sukhmati Hapka, the 38-year-old vice president of the Bijapur Gondwana Samaj, go with him.

The duo was taken on a motorcycle to a spot about a kilometre away, where six senior Maoists, headed by a lady commander in her early 50s, waited. They were later told that she was Manila, secretary of the Pamed area committee of the CPI (Maoist). “Her appearance was not so daunting, despite the uniform and the gun,” said Boraiya. “But her presence was quite intimidating.”

Boraiya and Hapka had a difficult task—to negotiate the release of Rakeshwar Singh Manhas, a member of the ill-fated CoBRA battalion, who was being held captive by the Maoists.

Meanwhile, a crowd was building in the clearing surrounded by the tamarind trees; villagers were pouring in—on feet, on bicycles and even on tractors. The afternoon sun was harsh. Despite the shade, the atmosphere was hot and oppressive. The tension only added to the discomfort.

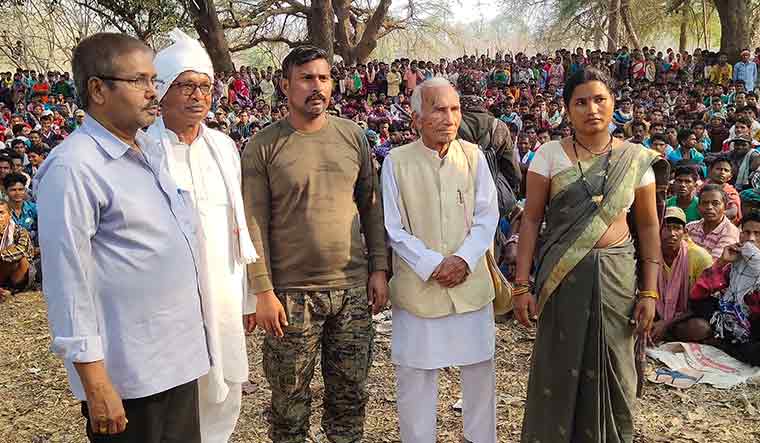

On the charpoy that Boraiya and Hapka just vacated sat Dharampal Saini, 91, Padma Shri awardee, Jagdalpur-based social worker and founder of the Mata Rukmini Ashram; he was accompanied by his associate Gururudra Kare. He had been told that he would be taken to meet the Maoist commanders once Boraiya and Hapka returned. After about 45 minutes, Boraiya and Hapka were brought back, but no summons came for Saini.

A while later, Manila and two dozen armed Maoists appeared. Saini, a promoter of girls’ education, noted with interest that almost half of them were women, some as young as 16 or 17 in his estimate.

Manila and some of the senior Maoists approached Saini and put some questions to him. First of all, they wanted to know his political affiliation. “I made it clear that I was an apolitical social worker, and I started my career under the guidance of the late Vinoba Bhave,” said Saini. “The Maoists looked satisfied.”

Manila told Saini that just as social workers like him appealed to the Maoists for securing the release of the commando, they should make similar efforts to protect innocent villagers from being harassed by the police and the administration. “She also asked me to ensure that the commando was sent back home at the earliest and they wanted to see his photograph with his family,” said Saini.

Manhas was brought in by around 3pm under armed escort; his hands were loosely bound with a rope. He was taken directly to the jan adalat (people’s court) organised by the Maoists. “He looked patient and composed, despite spending five days in captivity,” said Saini. By then, nearly a thousand villagers had assembled. As they sat in anticipation, Manhas was brought forward and his ropes were untied, the final act before his formal release.

The silent planning

The efforts to launch the mediation for Manhas’s release began on April 5. The day before, rescue teams had saved 31 injured soldiers and retrieved 22 bodies from the ambush site. As Manhas was not among them, he was reported “missing”.

Ganesh Mishra, a Bijapur-based journalist, got a call from the Maoists on April 5. They told him that they had Manhas and were willing to release him. Mishra and a few other journalists who received similar messages conveyed it to Sundarraj P., inspector general of police, Bastar Range. The formal offer was made through a press statement issued on April 6 by Vikalp, the spokesperson for the Dandakaranya special zonal committee of the CPI (Maoist). It said the Maoists were willing to release Manhas to government mediators.

After some local journalists raised doubts, the Maoists released a picture of Manhas, seated in a temporary shelter. Around the same time, Manhas’s friends and relatives blocked the Jammu-Akhnoor Highway on April 7 as they felt that the Union government was not doing enough to secure his release.

Tribal activist Soni Sori and members of the NGO Jail Bandi Rihai Samiti, too, had tried to intervene. They ventured into the forest, hoping to establish contact with the Maoists. But the attempt failed, and they returned on April 7 after leaving a letter for the Maoists with local villagers.

On the same day, Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel convened a meeting of Home Minister Tamradhwaj Sahu and senior officials in Raipur in an attempt to resolve the crisis.

Two surprise mediators

Senior police officers had contacted Saini on April 5 itself, seeking his help to mediate. Over a career spanning several decades, Saini has always confined himself to providing education for tribal children, especially girls. “I was somewhat surprised when the police sought my help. But as it involved saving a life, I agreed to cooperate,” said Saini. But he needed details. Whom was he supposed to meet and where?

On April 7, Saini was told that he would be taken to the Tarrem camp of the security forces at night and could proceed into the jungles the next day. He agreed, knowing that he would have to ride pillion for at least 30km on treacherous roads running through dense forests on a harsh summer day.

About 200km away in Awapalli, Bijapur district, Boraiya was also caught by surprise when the sub-divisional police officer approached him on the afternoon of April 7. Boraiya, too, agreed to mediate and, like Saini, asked for specifics. Kamlochan Kashyap, the Bijapur superintendent of police, briefed him over phone. “I was told that I would be taken to the Tarrem camp, about 30km from Awapalli, that night itself,” said Boraiya. “But as it was late, I suggested we leave at dawn. And, it was agreed.”

Both Saini and Boraiya were allowed to take along an associate each. While Saini chose Kare, Boraiya took Hapka with him. The four were to be taken to the rendezvous by a team of seven local journalists. The journalists—Mishra, K. Shankar, Ranjan Das, Mukesh Chandrakar, Yukesh Chandrakar, Chetan Kapewar and Ravi Punje—gathered at Basaguda, 12km from the Tarrem camp on the night of April 7. Mishra informed the Maoists about the plan and the names of the mediators and got their green signal to lead the party into the forest the next morning.

Trip to Tummel

The team of 11 left the Tarrem camp on six motorcycles on the morning of April 8. They were not given their final destination. Their instructions were to meet Maoist couriers at Jonaguda.

After the team left the Tarrem camp, a local youth entered the picture, someone whose mission and identity would cause a lot of confusion later. Kunjam Sukka was said to be a local guide, who accompanied the team to the site of the jan adalat. There was, however, speculation that he was a Maoist sympathiser or might even be a member of the pro-Maoist People’s Militia, who was detained by the police at the Tarrem camp after the April 3 ambush and was “released” in exchange for Manhas.

Later at the jan adalat, Sukka narrated how the police tortured him, but it was not clear to those present whether that was before or after the ambush on April 3. The mediators and the journalists were, however, unanimous that Manhas’s release was unconditional.

Sundarraj confirmed to THE WEEK that no Maoists or villagers were arrested after the ambush and, therefore, there was no question of releasing anyone. “Some local people helped the security forces during the rescue operations and a few of them stayed back at the camp and returned to their villages later. Sukka might be one of them,” he said.

The 11-member team reached Tummel by 8:30am, led by Maoist couriers who joined them on motorcycles at Jonaguda. The negotiators were met by mid-level Maoist operatives who welcomed them with cups of milk tea. They were then asked to wait.

Saini and Boraiya had discussed and agreed that they would stick to the limited agenda of securing Manhas’s release. They were not going to discuss anything further with the Maoists. Saini said most of the people assembled for the jan adalat were young. “I saw young men dressed in modern apparel like jeans, shorts, trousers and shirts. I managed to speak to a few young girls who were sitting close by and I was happy to note that they were all pursuing studies,” he said. Saini also observed that while most houses he saw were made of mud and were thatched, those were well maintained, colourful and equipped with solar lights.

Mishra, 37, said this was the first time that such a jan adalat was held to release a “high-profile hostage”. He had attended a few such events in the past when local cops were released. “I certainly was not afraid. After all, the Maoists themselves had made an offer to us to come with the mediators to secure the jawan’s release,” he said.

As they kept waiting for Manhas, the team was served a lunch of rice, tomato chutney and a curry of fish, fresh from a nearby pond; all cooked by villagers at the instance of the Maoists. Being a vegetarian, Saini stuck to rice and chutney. Once they finished lunch, Boraiya and Hapka were taken to meet Manila and her associates.

The discussion

Acutely aware of the life-saving mission they were on, Boraiya and Hapka started answering Manila’s questions. She was flanked by two female and three male commanders, and she spoke with an accent of a non-tribal, probably of south Indian origin. The questions came fast: What exactly was Boraiya’s social position? How did they come about to be part of the delegation? Which political party were they affiliated to?

Boraiya was candid and told Manila about how senior police officers spoke to him about Manhas and convinced him that initiative from community leaders was necessary to secure his release. “I told her that I agreed to mediate also because I had seen the videos of the captive’s family, including a fervent appeal by his little daughter,” he said. “I said that if something untoward happened, it would be very tragic and painful.”

Manila told Boraiya that she, too, had seen the videos and was aware of the family’s pain. She said she knew that Manhas was from Jammu and had joined CoBRA in Bastar only four months ago and, as such, had not caused any harm to the locals. She said he was found unconscious by her cadre several hours after the ambush. They gave him food and water and also medical aid. She assured them that he was fine and would be released soon.

After this, Manila started talking about the alleged excesses of the police and how locals were being arrested without warrants. She said they were often beaten, women subjected to physical and sexual violence, and their meagre belongings looted. She wanted community leaders like Boraiya and Hapka to take up the issue with the police and the administration. On a lighter note, she added that if the police did not care about the people, why should the Maoists care about the police.

Boraiya assured her that as community leaders they were always ready to help people who faced injustice. He also promised to take up the matter with authorities if the people approached them. “I told her that the local people probably did not consider me as someone to be approached for such matters,” he said. “But if they do, my associates and I will certainly help.”

Discussions—mostly in Hindi, interspersed occasionally with the native Gondi—continued for almost 45 minutes. “Finally, we were asked to go back and wait with others. We were told that Manhas would be released soon, but only after he gave a testimony before the jan adalat about how the Maoists treated him in captivity,” said Boraiya.

In the people’s court

Manhas was brought to the jan adalat an hour later. As the waiting journalists started shooting videos and photographs, Boraiya objected to the Manhas’s hands being tied. But Manila told him that it was part of the jan adalat process and was not intended to harm or disrespect Manhas.

The Maoists then formally started the jan adalat by informing the people present about the way Manhas was taken into captivity and asked them whether he should be set free. A small section of the crowd objected, saying the security forces often harassed, arrested and even killed innocent villagers. Some of them presented testimonies of such alleged excesses.

The Maoist commanders said Manhas personally never harmed anyone and, therefore, it was not correct to punish him. A majority agreed, sealing his release. Manhas was then asked to speak about how he was treated in captivity, to which he replied that he was given medical aid and food, and was not harassed in any manner. He also explained how he got separated from his team during the ambush and passed out because of dehydration, following which he was taken captive by the Maoists. He said he did not know where he was kept as he was moved repeatedly and was always blindfolded. He also expressed gratitude to the mediators and the journalists for facilitating his release.

Saini had by then conveyed the news of the release to Manhas’s family in Jammu over telephone. “A while later, as I found myself close to him, I told him that I spoke to his family and that they were delighted to hear the news. A slight smile spoke of the happiness he felt,” said Saini.

Journey back to safety

As journalists proposed waiting a little longer at the spot for more elaborate interviews, the seasoned Saini realised that Manhas’s safety was now their responsibility and it was important to return to the Tarrem camp at the earliest. At his insistence, the Maoists made an appeal to the crowd to provide the team safe passage back to the camp.

Saini then directed the team to leave the spot immediately. Manhas rode pillion with Shankar and could be heard asking him to go fast. As the six motorcycles started the journey back, Saini noticed a look of relief on Manhas’s face for a fleeting moment, a break from the composure he had maintained for hours.

The extremely tired, but exceedingly happy team reached the Tarrem camp at around 6:30pm, and Manhas was formally handed over to Komal Singh, deputy inspector general of the CRPF. After a thorough medical examination, he spoke to his family members and to Union Home Minister Amit Shah. He was treated at the Basaguda field hospital and later at a hospital in Jagdalpur. “Manhas continues to be under observation,” said Sundarraj. “He is likely to be granted leave once he is found fit for travel.”

Manhas is expected to return to Jammu on April 16 and will be accompanied by a few members of the rescue team. Sources told THE WEEK that Boraiya, Mishra and Mukesh Chandrakar are likely to accompany him to Jammu.

Baghel felicitated Manhas, Saini, Boraiya, Kare, Hapka, Mishra and Mukesh Chandrakar in Raipur on April 12. “No praise could be enough for the work that the mediator team has done,” said the chief minister. “Not just the people of Chhattisgarh, but the entire country had its eyes on the developments. The members of the team acted as responsible citizens and undertook their task with courage.”

Guru of Bastar

Dharampal Saini was THE WEEK’s Man of the Year in 2012.

Born in 1930 in the princely state of Dhar, now part of Madhya Pradesh, Saini was the second of four children. His father was the head of the horticultural department in Dhar. At school, Saini’s commerce teacher introduced him to the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. He soon began working with Gandhian institutions like the Bhil Seva Sangh, which worked for the uplift of the Bhil tribe of western Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat.

Saini was 46 and a confirmed bachelor when he set out to Bastar. Essentially a jungle bigger than Belgium, Bastar was then severely underdeveloped, rich in mineral resources and plagued by the Maoist threat. Saini had the blessings of his mentor, the venerable Gandhian Vinoba Bhave, to set up an ashram in Dimrapal, a village near the district headquarters of Jagdalpur.

Saini opened a primary boarding school for girls in December 1976, with two teachers and two support staff. The modest initiative grew, and by the time Saini won the THE WEEK’s Man of the Year award, his ashram had 37 residential schools—21 of them for girls—spread across Bastar. Nearly 20,000 girls had been educated.

“Bastar has come a long way,” Saini told THE WEEK’s special correspondent Deepak Tiwari in 2012. “Earlier, hardly any government employees wanted to come here and the posts were always vacant. Those posts are now filled by the natives of Bastar, because of education.”

All of five feet and four inches, Saini does not cut an imposing figure. But he commands great respect among the people of Bastar. Affectionately called tauji, Saini always wears khadi clothes, stays in a two-room kuccha house, filled with books and bags of seeds for the next sowing season. “It will take the next two generations to completely eradicate this [Naxal] menace,” Saini said. “I am hopeful that Naxalism will end. There is no reason why it should not, with the spread of education.”