In January, Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley left for the United States just before the crucial budget session. Despite concerns about his health and the uncertainty over who would present the Union Budget, sources maintained that Jaitley had gone for a “regular medical checkup”. However, there are unconfirmed reports that he has been diagnosed with a form of soft tissue sarcoma, and has been undergoing treatment in New York.

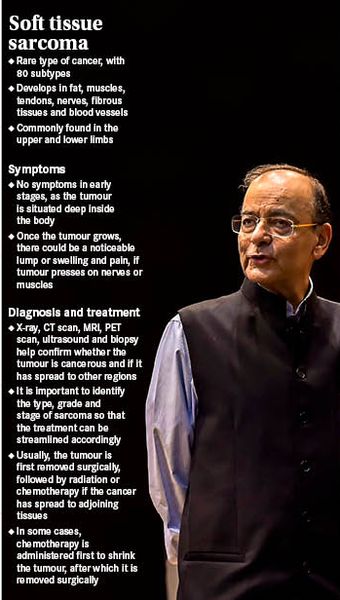

The speculation has resulted in a focus on rare cancers of the soft tissue. Soft tissue sarcomas occur in fat, muscles, tendons, nerves, fibrous tissues and blood vessels. A tumour in the soft tissues is not uncommon, but the suffix ‘sarcoma’ is used when a tumour is found to be cancerous.

“Soft tissue sarcomas are rare, and the incidence of the disease is around one to two per cent globally. In India, at a centre such as ours [Tata Memorial Hospital], the figure stands at about 2 per cent only because we are a referral centre,” says Dr Bharat Rekhi, professor, department of pathology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai.

These complex tumours grow over a period of time, and are often deep-seated in the body. Hence, they end up getting ignored. “These are lumps situated deep inside the body, and so, they often get diagnosed at a late stage, making them very difficult to treat,” says Rekhi, also ex-convener of Tata hospital’s bone and soft tissues disease management group.

Though soft tissue sarcomas can be found in any part of the body, they are usually found in the body’s peripheral (upper and lower limb) region. They can also be found in the central (abdominal and chest) region. “The peripheral ones, which are more common worldwide, are easy to diagnose and treat than those found in the central one,” says Dr Vijay Anand Reddy P., director, Apollo Cancer Institute, Hyderabad. He is also the president of the Association of Radiation Oncologists of India.

In case of soft tissue sarcomas, the diagnosis is very important, says Rekhi. A pathologist has to grade, stage and identify the type of sarcoma—there are 80 different kinds, like liposarcoma (fat cells) and angiosarcoma (blood and lymph vessels)—which will determine the kind of treatment to be given. “Understanding the type is important because that determines how the tumour will behave. Each person is different and the treatment has to be tailored to every individual. A multidisciplinary approach is needed,” says Rekhi.

If detected on time, the tumours can be removed through surgery and the cure rate is high. Along with the tumour, says Reddy, 1-2cm of normal tissue around it is also removed. After surgery, if the cancer cells are found along the edges of the excised tissue, it is defined as having “negative margins”, and more treatment such as radiation might be needed.

At the Tata Memorial Hospital, Rekhi says they often get cases where surgeries have been botched up—incomplete or unnecessary surgeries. “Sometimes, for instance, the right way would have been to first administer chemotherapy and shrink the tumour, before removing it surgically,” he says. Only a few centres in the country are able to handle these complex cases, and hence it is important for experts on the subject to collaborate on these cases.

In cases where the tumour has been detected late and the cancer has spread to other parts, the cancer can only be managed, and not cured, says Reddy.

The trouble with soft tissue sarcomas is that early detection, say, through imaging or a pap smear like in breast or cervical cancers, is not possible. “Unless patients present themselves to the doctor with unusual symptoms and lumps, the cancer cannot be detected,” says Reddy.

Experts working on sarcomas—soft tissues and bones—say that newer treatments are in the pipeline and collaborative efforts are on to treat these rare but challenging tumours. For instance, for osteosarcoma, the most common cancer that develops in the bone, a new treatment protocol has been developed by experts at the Tata hospital. Dr Jyoti Bajpai, associate professor, medical oncology, says that she and her colleagues have developed the OGS-12 protocol—a regimen comprising three drugs, where toxicity is predictable, and so more manageable, unlike the standard high-dose regimen, where it is unpredictable. Also, it does not require the patient to be admitted to the hospital. “This is an indigenously developed treatment, and has shown results that are equivalent to the standard treatment,” says Bajpai. Though immunotherapy, the buzzword in cancer treatment currently, has not shown much promise in bone and soft tissue sarcomas, it has recently been approved for muscle cell sarcoma, she says.