Half a century ago, a plot to kidnap Indian high commissioner Samar Sen in Dhaka was foiled by the timely intervention of his security personnel. A leaked Wikileaks cable describes what happened on that fateful morning on November 26, 1975, when six young men, disguised as visitors, pulled out revolvers and moved towards Sen as he stepped out of his car in front of the Indian High Commission in Dhanmondi, an upscale neighbourhood. Security guards rushed in, exchanged fire and secured Sen, beating back the assailants.

Following the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in August 1975, the first wave of anti-India sentiment began to emerge in Bangladesh. The coups and counter-coups that finally brought General Ziaur Rahman to power gave fresh ammunition to a section of the post-liberation leadership—consisting largely of leftist groups and radical freedom fighters—to vent against pro-India policies and the country’s alleged influence on Bangladesh’s foreign policy and politics. This sentiment resulted in Zia’s consolidation of power, opening space for all parties, including Islamist outfits such as the Jamaat-e-Islami and secular parties like the Bangladesh Awami League, while realigning Dhaka’s foreign policy to improve diplomatic ties with the Islamic world as well as Islamabad.

For the ordinary Bangladeshi, resentment towards India continued to grow, driven by high prices of Indian goods, excessive use of water from rivers flowing into Bangladesh and a trade imbalance in India’s favour. New Delhi, in turn, was upset with the persecution of religious minorities in Bangladesh and insurgent groups on its borders finding safe havens on Bangladeshi soil.

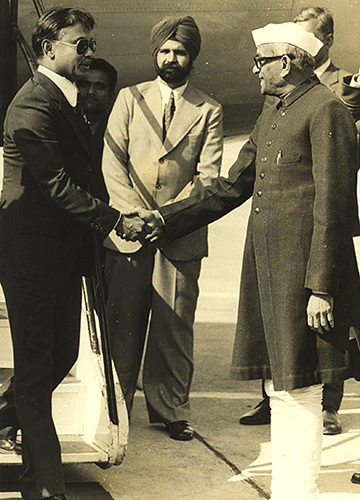

It took deft statecraft by prime minister Morarji Desai and Zia to turn hostility into constructive engagement. Zia had barely shed his military uniform when he visited New Delhi in December 1977, setting the stage for a friendship that brought some cheer to people on both sides. A joint communiqué noted that the historic Farakka Treaty on the sharing of Ganga water, signed in November, was made possible “because of the spirit of mutual accommodation and understanding shown by the leaders of the two countries”. It also listed a string of efforts to improve relations, including the creation of a joint commission on irrigation water allocation, boundary disputes, proposals for the exchange of small enclaves and even the sale of cement, urea fertiliser and other products to India. Beyond business, Zia’s public gesture of visiting the samadhi of Mahatma Gandhi at Rajghat and the Dargah-e-Sharif of Hazrat Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti at Ajmer struck a chord.

Equal warmth was displayed during Desai’s visit to Dhaka in 1979, when he underlined good neighbourly policies as the way forward for the two countries bound together by geography, tradition and culture. Interestingly, it was during this phase of de-escalation that India facilitated the return of Sheikh Hasina, living in exile after her father’s assassination, to Dhaka after she was elected president of the Bangladesh Awami League.

“Over time, successive regimes have used the anti-India sentiment for political gains, yet chose engagement over isolation,” says Asif Bin Ali, a doctoral fellow at the Georgia State University. “The lessons have been foundational. While Bangladesh’s internal politics can be adversarial towards India, its governance cannot be, because economic and regional stability are intertwined with functional ties with Delhi.”

In the last 50 years, Bangladesh’s relationship with India has suffered three distinct phases of animosity running through regime changes: Zia’s takeover, Begum Khaleda Zia’s government and the incumbent interim government run by Muhammad Yunus. The outcomes of the first two ranged from pragmatic cooperation to deepening ties. The outcome of the third will stand the test of time and reflect the vision of its leaders as Bangladesh races towards parliamentary elections on February 12.

After Zia’s assassination in 1981, the Delhi–Dhaka relationship remained largely dormant until Sheikh Hasina signed the Ganga water treaty in 1996 with prime minister H.D. Deve Gowda. A red carpet was rolled out for Gowda during his first visit to Dhaka, celebrating the “soft diplomacy” of his foreign minister, Inder Kumar Gujral, extending beyond the Ganga. Hasina signed the peace treaty on the Chittagong Hill Tracts in 1997 to curb insurgent activity and ease long-standing tensions.

The pragmatic relationship between the two countries continued into the 1990s, but India resisted the temptation to pick favourites. While it enjoyed close ties with Hasina, it continued engaging the opposition. “Our outreach was to every section of society. We remained friendly with whoever was in opposition,” says a former Indian official posted in Bangladesh.

Ironically, it was Hasina’s tilt towards India that triggered the second anti-India wave and brought the Bangladesh Nationalist Party to power in 2001. Yet, India’s pragmatic approach paid dividends. Despite tensions between the two countries, the first high-profile visit to Dhaka was by Brajesh Mishra, then national security adviser to prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who arrived with an explicit message that New Delhi would engage Bangladesh regardless of who occupied power.

Bridging the distrust, however, was not easy. Anti-India elements argued that Delhi would always favour the Awami League. “Commerce was high on the agenda and negotiations began on export items,” says an official, “but the talks collapsed over rules of origin as Bangladesh sought to export goods not even manufactured locally, routing Chinese products into India.” The breakdown of trust between Dhaka and Delhi created a second opening for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, say security experts, to expand its footprint. Bangladesh then entered a dark phase under the BNP-Jamaat coalition, further restricting Delhi’s room for manoeuvre.

Delhi’s options are again limited with the interim government holding power in Dhaka since August 2024. “Since it is an interim government, there is no time for major initiatives,” says a senior diplomat. “At the same time, substantive engagement should begin with successive governments.”

The challenge, again, is the systematic rise of anti-India sentiment. While the exclusion of the Awami League and Hasina’s exile in India is seen as the primary reason for prolonged unease in the relationship, often bordering on suspicion and anger, there is more to it than meets the eye. Attacks on the Indian High Commission, media houses and cultural institutions ahead of the elections demonstrate New Delhi’s narrowing options.

“The direction of anger towards the Awami League and India has become a characteristic feature of post-2024 politics, often the two becoming synonymous, serving the purpose of both Islamists and their patrons,” says Smruti Pattanaik, research fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. “Such insinuations against India and the Awami League free the interim regime of responsibility and accountability for the large-scale arson that followed.”

Disengagement, meanwhile, has its own dangers. While there may be little substantive content in Bangladesh-Pakistan relations, there is significant mischief potential. Historically, Pakistan has exploited anti-India sentiment through Islamist networks and insurgent proxies. That risk, Indian officials believe, has not disappeared.

Therefore, while the catalysts pushing the Delhi-Dhaka relationship to the edge may be different this time, the answer may still lie in revisiting Delhi’s old Bangladesh playbook. New Delhi needs to engage the Bangladeshi political spectrum for precisely the reasons it finds it difficult to do so. Students who led the 2024 protests are now organised under the National Citizen Party. The Jamaat’s street muscle and mass mobilisation capacity have been demonstrated repeatedly. Finally, the BNP’s primary seat in the opposition makes it a contender for the Awami League’s space when elections are held. “Given Bangladesh’s grim history of political transitions marked by violence, broad engagement will leave the door open for sharing common concerns,” says Ali.

Once a new government is elected in Dhaka and rapprochement becomes a priority, India has a range of instruments to build popular goodwill in Bangladesh. “India could lift restrictions on visa issuance as well as transhipment rights through Indian seaports. Both countries could also revive negotiations towards a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement,” says Constantino Xavier, senior fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, New Delhi. “To counter negative perceptions, India might also announce a new package of lines of credit and grants to support health and education projects. India can also announce a unilateral extension of all rights under the Ganga water treaty, set to expire in 2026.” Xavier believes the most symbolic measure would be India acceding to Bangladeshi demands on the Teesta water and renewing the 2011 package vetoed by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee.

Internal politics has always influenced cross-border ties. With West Bengal holding assembly polls in 2026, the BJP’s performance could pave the way for new economic connectivity and bilateral water and energy initiatives. Politics aside, it is imperative for Delhi and Dhaka to engage on economic issues.

Each year, lakhs of people cross the India-Bangladesh border, including students, patients, traders, pilgrims, tourists and families living across the divide. Delhi and Dhaka cannot afford further delay. For nearly two years, the world’s first and eighth most populous countries have seen no significant dialogue between policy researchers, academics or industrialists. “Think tanks, universities and economic actors need to do a better job of sustaining track-two dialogues, not just when all is well but especially when the Indian government is facing difficulties with neighbouring countries,” says Xavier. “Dhaka, too, has been missing in action.”