It may have been Hurricane Melissa, which exploded into a Category 5 storm on October 27, that inadvertently saved 18 undocumented immigrants from the Guantánamo Bay detention centre. As the storm swept across the Caribbean, the American National Weather Service issued warnings that it could reach Cuba, prompting officials to evacuate the group quietly. They were flown by a special aircraft to Guatemala and El Salvador, their names and nationalities withheld. The operation, conducted in secrecy, also allowed the Trump administration to wriggle out of a legal crisis. It came just days before a federal court hearing that could redefine the legal boundaries of offshore migrant detention.

Guantánamo Bay has returned to the headlines as the Trump administration has started using it to detain undocumented migrants. President Donald Trump signed a memorandum in January this year, instructing the expansion of the Migrant Operations Centre at Guantánamo to full capacity. The memorandum directed the secretaries of defence and homeland security to detain high-priority criminal aliens. Trump claimed that the base could hold up to 30,000 people, presenting it as part of his promise to carry out the largest deportation in American history.

The move drew immediate condemnation from human rights organisations. They argued that it exploited the base’s peculiar legal status—technically outside US territory but under American control—which allowed migrants to be held in a jurisdictional gap with limited access to legal counsel and courts. The American Civil Liberties Union launched a legal challenge, arguing that the practice was unconstitutional and violated international law.

Central to the debate is whether migrants detained at Guantánamo have the same legal rights as those held on US soil. In Gutierrez v. Noem (2025), two Nicaraguans who had been held in immigration detention at Guantánamo argued that they do have the same rights. Judge Sparkle L. Sooknanan of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia is considering class action status, which would allow the ACLU to represent all migrants held at the base. The ACLU says the government’s use of Guantánamo is a deliberate attempt to bypass domestic due process protections. “The government is effectively disappearing these people into a legal black hole,” said Lee Gelernt, deputy director, ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project. “The lawsuit is not claiming they cannot be detained in US facilities, but only that they cannot be sent to Guantánamo.” On December 5, Judge Sooknanan denied the Trump administration’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, allowing the legal challenge to proceed.

Since February, the Trump administration has detained roughly 710 migrants at Guantánamo, far below the tens of thousands envisioned initially, reflecting both logistical constraints and growing legal scrutiny. The first detainees—ten men allegedly connected to Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua gang—were flown in from Texas on February 5. At its peak, the migrant detention operation held 178 Venezuelans, on February 19. But most were repatriated or relocated quickly. Currently, there are no migrant detainees. Officials insist the detentions comply with longstanding US maritime and migration policy, which since the 1990s has allowed the holding of migrants intercepted at sea. The ACLU, however, argues that these migrants were detained on American soil, rather than intercepted at sea.

LONG BEFORE it became synonymous with barbed wires, orange jumpsuits and legal ambiguity, Guantánamo Bay was a quiet American outpost amid the turquoise waters and green hills of southeastern Cuba. Guantánamo’s modern history began in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, sparked by US intervention in Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain. Tensions were already high when the explosion of an American warship in the Havana Harbour propelled the US into war. Fighting spread across the Caribbean and the Pacific, from Cuba and Puerto Rico to Guam and the Philippines. By the end, Spain lost its remaining overseas empire and Cuba came under temporary American occupation.

The US Marines who landed at Guantánamo Bay quickly recognised its military value. It offered a deep, sheltered harbour near sea routes linking the Atlantic with the Caribbean and, later, the Panama Canal. Following Spain’s defeat, the Treaty of Paris (1898) formalised Cuba’s independence, but the US was allowed to intervene in Cuban affairs to “preserve order and independence”. It also permitted the US to buy or lease Cuban land for naval stations, allowing the establishment of the American base at Guantánamo.

While recognising Cuban sovereignty, the agreement gave the US complete jurisdiction and control over the territory. The Guantánamo Bay Naval Station is now the oldest American military installation on foreign soil, serving as a refuelling and repair hub. For decades it was the winter training base for the Atlantic Fleet.

In 1934, under president Franklin D. Roosevelt, the US repealed some of the most interventionist clauses of the earlier agreement with Cuba, but left the Guantánamo lease intact. The new treaty stipulated that it would remain in force until both nations agreed to modify or terminate it, ensuring its near-permanent status. The US agreed to pay an annual rent of $2,000 to Cuba, later increased to $4,085.

For much of the 20th century, relations between the base and surrounding Cuban communities were relatively stable. This changed with Fidel Castro’s revolution. In 1958, fighters under Fidel’s brother Raúl briefly captured 29 American sailors near the base, foreshadowing tensions to come. Since Fidel Castro’s revolution, Cuba has refused to cash the rent cheques, arguing that the US presence is an illegal occupation. By 1961, the US had withdrawn its embassy, and in 1964 Cuba cut Guantánamo’s water supply, forcing the base to become entirely self-sufficient.

From then on, Guantánamo has operated as an island within an island. It generates its own electricity from fossil fuels, solar panels and wind turbines and produces water through a desalination plant. A fortnightly barge from Jacksonville, Florida, delivers food and goods, while twice-weekly flights bring fresh produce. Over time, Guantánamo has become a self-contained American community of several thousand people, with schools, churches, a post office, sports fields and fast-food outlets, including McDonald’s—the only one on Cuban soil.

Throughout the Cold War, even as Cuba and the United States stood opposed to each other, everyday life carried on in oddly ordinary ways on Guantánamo: families barbecued, children played baseball and American and Cuban soldiers sometimes traded music or exchanged brief waves across the fence. The base formed its own isolated ecosystem in the tropical heat, best known for its banana rats and its iguanas, strictly protected under US environmental rules. These quirks heightened the sense of absurdity: a fortified outpost where wildlife regulations were rigorously upheld while international legal norms often felt conspicuously absent.

In the early 1990s, as the Cold War drew to a close, Guantánamo took on an unexpected humanitarian role as Haitians and Cubans fled their countries by sea. Following a military coup in Haiti in September 1991, thousands attempted the dangerous crossing to escape political instability. By the end of that year, more than 6,000 Haitians were housed on US Navy ships and in makeshift camps at the base. In 1994, a task force was set up to process over 40,000 Haitian migrants.

That same year Guantánamo became the site of the world’s first and only prison camp for people with HIV, where more than 300 Haitian refugees, including children, were held behind razor wire. “These were refugees fleeing slaughter in their country, whose credible fear of persecution US officials acknowledged, yet they were held for no reason other than their HIV status. When they protested detention, the response was brutal,” Pardiss Kebriaei, senior staff attorney at the New York-based Centre for Constitutional Rights, told Voice of America.

The ambiguity deepened after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, when Guantánamo transformed from a quiet post to the centre of America’s campaign against terrorism. The George W. Bush administration wanted a site to detain and interrogate suspects captured in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Guantánamo, under complete US jurisdiction yet outside the reach of civilian courts, was chosen for its isolation and unique legal standing. With the new detention camp, it shifted overnight from a sleepy Caribbean outpost to a cornerstone of the war on terror.

Its unusual sovereignty arrangement provided justification for detaining foreign nationals without constitutional rights. On November 13, 2001, Bush authorised the detention of non-citizens suspected of terrorism. Within weeks, refurbishment of old refugee compounds and construction of new prison blocks began. By January 2002, the first 300 detainees arrived from Afghanistan and were placed in the hastily built Camp X-Ray.

Images of hooded, shackled men in orange jumpsuits shocked the world. Pentagon photographs became symbols of the post-9/11 era. Camp X-Ray was intended as temporary while permanent facilities were built, yet it set the tone for Guantánamo’s reputation.

Legal challenges gradually eroded claims that Guantánamo lay beyond justice. In Rasul v. Bush (2004), the US Supreme Court ruled detainees could challenge imprisonment. Later decisions, including Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006) and Boumediene v. Bush (2008), reinforced those rights, yet many prisoners remained detained despite favourable rulings due to bureaucratic and political obstacles. By the late 2000s, Guantánamo had become a political and moral burden. Barack Obama pledged to close the facility in 2008, describing it as incompatible with American ideals. Yet Congress blocked transfers to the mainland, and the prison remained open with a declining population.

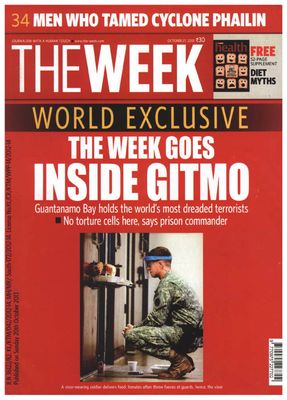

When THE WEEK visited Guantánamo Bay in 2013—the only Indian publication to be allowed access—it found that the prison remained fully operational despite Obama’s promise. Guantánamo was a virtual fortress. Barbed wire, watchtowers and cameras encircled the site, while armed patrols monitored roads and the coastline. Guards were identified by numbers rather than names to preserve anonymity and prevent personal contact with detainees. Escape was impossible. Motion and sound sensors guarded the US perimeter, while the Cuban side was sealed off by mines and a 13km cactus barrier. Even senior Pentagon officials required multiple security clearances to enter.

At the time of the visit, Guantánamo held detainees from 48 countries. The prisoner population reflected the chaotic nature of the early detentions. Hardened militants were held alongside farmers, clerics, journalists and teenagers. Case files revealed that at least 17 detainees had been under 18 at capture, with two as young as 14. Many had endured years of interrogation before being declared innocent and released. One interpreter told THE WEEK that the greatest injustice was that many at Guantánamo had never been tried, while convicted terrorists elsewhere had received legal hearings.

Military officers admitted that several prisoners were victims of mistaken identity or opportunism. During the early years of the ‘war on terror’, US forces distributed leaflets across Afghanistan and Pakistan offering rewards of $5,000 for captured terrorists. This bounty system led to numerous false arrests as Afghan warlords and Pakistani soldiers sold innocent men for profit. One Afghan, 19-year-old Obaidullah, was imprisoned because bloodstains were found in a van. It was later revealed that it belonged to his wife, who had given birth inside it. Others were detained for owning the Casio F-91W watch, which US intelligence wrongly believed was used as a bomb timer by al Qaeda recruits.

The detention complex was divided into several camps. Camp Iguana, which once held minors, housed three Chinese Uyghurs who had fled persecution and been sold for bounties. Camps 5 and 6 contained most of the 164 detainees. Camp 5, a maximum-security block, confined inmates for up to 22 hours a day in small, monitored cells. Of its 58 detainees, 46 were classified as indefinite, meaning they could be held without trial or release. Camp 6 provided slightly improved conditions, allowing compliant prisoners up to nine hours outdoors. Their cells held a bed, a metal sink and a toilet, and they were permitted a Quran, writing materials and books. Even so, detainees arrived blindfolded and were subjected to intrusive searches when entering or leaving the compound.

Fifteen high-value prisoners were kept in the secretive Camp 7. Among them was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-proclaimed architect of the September 11 attacks, who was reportedly waterboarded 183 times in a single month. Another detainee, Abu Faraj al-Libbi, al Qaeda’s former third-in-command, misled interrogators about Osama bin Laden’s whereabouts for years. Interrogation rooms were painted blue to induce calm, but accounts described degrading methods including sexual humiliation by female interrogators who touched detainees or smeared fake menstrual blood on their faces.

The psychological toll was severe. The prison hospital treated inmates daily for depression, psychosis and hallucinations. At least seven suicides had been recorded. One detainee, Adnan Latif, a Yemeni cleared for release twice, died of a medication overdose in Camp 5.

THE WEEK was shown a small room with a television, and was told that detainees who comply could watch shows, but they would be shackled to rings on the floor. And, television is not just entertainment, it is an intelligence gathering tool, too. “They watch live satellite television. So, they are very appraised about world developments,” Captain Robert Durand, the facility’s spokesman told THE WEEK. “When you look at strategic intelligence, it is a question of association—people who they went to school with, people who they trained with.... So, there is utility to it [giving access to TV to prisoners.].”

While commanders insisted that prisoners were treated humanely, Amnesty International condemned Guantánamo as “a gulag of our times”, highlighting the injustice of indefinite detention without charge. Of the 164 detainees held in 2013, at least 84 had been cleared for release, yet bureaucratic deadlock prevented their departure. The US state department sought to persuade foreign governments that these men posed no threat, while the justice department argued in court that they could still be detained because of suspected terrorist links.

Officials at the base admitted that rehabilitation was not a goal. The aim was simply to keep detainees off the battlefield. Preparations were under way for the first US war-crimes trial in 50 years, to be held at Camp Justice, a temporary courtroom complex of more than a hundred tents. For all the defences offered, THE WEEK concluded that Guantánamo remained a symbol of moral and legal paralysis, suspended between security and justice and contradictory to the principles it claimed to uphold.

Since 2002, about 780 men have passed through the detention facility. Under president George W. Bush, around 540 were transferred, mostly to their home countries. The Obama administration continued the process, arranging the repatriation or resettlement of about 200 detainees. During Donald Trump’s first term, only one man was moved, to a prison in Saudi Arabia. The Biden administration repatriated 13, transferred 11 to Oman and released one, leaving just 15 men still held at the base as of November 20, this year.

Today, Guantánamo Bay stands as an unresolved paradox. It is a functioning naval installation, a diplomatic irritant, a legal anomaly and a moral question. “Guantanamo was a mistake. History will reflect that,” said Major General Michael R. Lehnert, the first commander of Joint Task Force Guantanamo. “It was created in the early days as a consequence of fear, anger and political expediency. It ignored centuries of rule of law and international agreements. It does not make us safer and it sullies who we are as a nation.”

FROM THE ARCHIVES

When THE WEEK went to Guantánamo Bay

Scan code to read the story