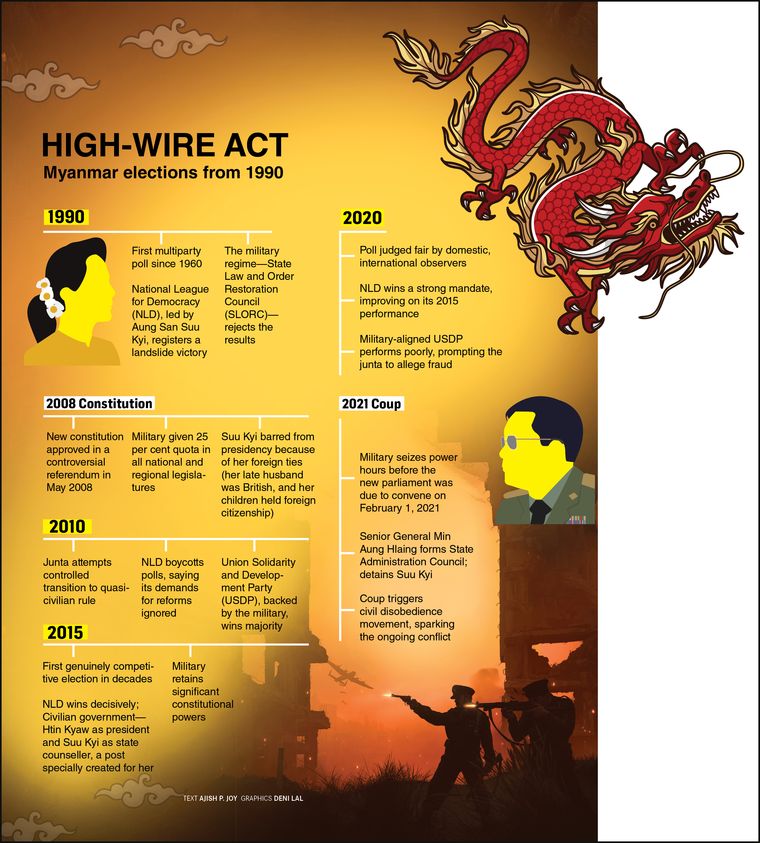

When Myanmar’s military junta, the State Administration Council (SAC), announced in January that it would hold national elections by December this year, the declaration was met with more scepticism than surprise. For a country torn apart by civil war since the 2021 coup, the idea of staging a credible election sounds almost farcical. After all, how does the junta plan to conduct a national poll when barely 40 per cent of the country is under their control, resistance forces are tightening their grip on highways and arms factories and large swathes of rural Myanmar remain no-go zones for government officials? Against this backdrop, the proposed elections seem less a democratic milestone and more like a political theatre.

The Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) retains nominal control in cities and urban centres, and its grip on the hinterland is tenuous. Resistance groups, once fragmented, now operate with remarkable coordination. In the south and southeast, they have displayed impressive strategic acumen, making steady advances towards capital Naypyidaw. Their latest push across the Sittaung River valley and into the Pegu Yoma range brings them closer to the Mandalay–Naypyidaw–Yangon highway, one of Myanmar’s two critical arteries.

Meanwhile, in the north and northeast, groups have seized control of strategic chokepoints on the Pathein–Monywa highway, a route linking several key ordnance factories vital to the Tatmadaw’s war machine. With these supply lines choked, the junta’s military position grows increasingly precarious. Resistance networks, particularly the Arakan Army and allied forces, now exercise control over regions that once sustained the Tatmadaw’s logistics.

The junta is locked in an existential war, so diverting resources to elections could further weaken its battlefield position. Moreover, without secure access to rural areas, the mechanics of voting become unworkable. Resistance leaders have made it clear that any attempt by the SAC officials to enter their territories will be fiercely resisted. Should the junta push ahead, the elections risk being accompanied not by ballots but by bullets.

Public sentiment is equally hostile to the plan. A 2024 survey shows that over 93 per cent of the people back the National Unity Government (NUG), the shadow administration formed by ousted lawmakers and resistance leaders. The NUG has already denounced the election as a sham. As a result, even in urban centres where the military still holds some sway, enthusiasm for voting appears minimal. What the SAC envisions as an assertion of legitimacy is more likely to be read as another desperate ploy to cling to power.

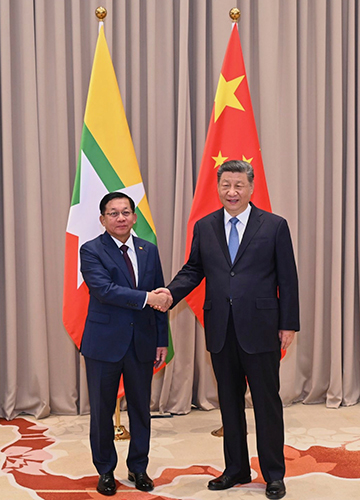

Why, then, is the Tatmadaw so determined to persist with its electoral plans? The answer may lie in the regime’s need for constitutional veneer. The SAC, established by force rather than through popular will, lacks the ability to amend Myanmar’s constitution. A staged election, however hollow, could provide the façade of parliamentary procedure, enabling the junta to push through amendments. Among the most worrying possibilities is an amendment that would legalise the deployment of foreign forces in Myanmar, read Chinese. This could open the door to Chinese intervention on behalf of the Tatmadaw. Thus, the junta’s desperation to project legitimacy also creates space for Beijing’s manoeuvring.

For Beijing, whose strategic and economic stakes in Myanmar are immense, propping up the junta with superior firepower may appear attractive. Chinese investments in Myanmar include pipelines, ports and special economic zones. Myanmar also provides an alternate access point to the Indian Ocean region, thereby easing President Xi Jinping’s so-called Malacca dilemma. Constitutionally sanctioned foreign troop deployments would allow China to formalise its support for the Tatmadaw. Chinese forces, equipped with superior technology and resources, could tilt the battlefield balance decisively.

Yet, the costs are equally clear. Such a move would clash with the deep anti-China sentiment now running through Myanmar’s populace, raising the risk of backlash similar to that which doomed the Myitsone hydropower project. Also, the Chinese Communist Party is unlikely to absorb battlefield losses without political repercussions at home. For now, Beijing appears cautious, preferring to arm and advise from the sidelines while waiting to see which way the war turns. Still, the mere possibility of China embedding itself militarily in Myanmar is enough to alarm security planners in New Delhi.

For India, Myanmar’s turmoil is an urgent neighbourhood crisis that reverberates across multiple domains. Peace and stability across the border directly affect security in India’s northeast, where insurgent networks often seek shelter inside Myanmar’s porous frontiers. These include groups such as the National Socialist Council of Nagaland and its offshoots, United Liberation Front of Asom and Manipuri rebel outfits. Destabilisation across the border could undermine years of hard-won stability in the northeast. The crisis also carries a humanitarian dimension, as refugees continue to flow into Mizoram and Manipur. Ethnic affinities, particularly between the Mizo and the Chin, make deportation politically and socially sensitive, yet unchecked migration threatens to inflame fragile demographic balances, leading to instability and widening fissures between communities within India’s borders, as in Manipur.

Equally pressing are India’s connectivity ambitions. Flagship projects such as the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Project and the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway were designed as the arteries of India’s Act East Policy, anchoring India’s physical and economic integration with southeast Asia through the northeast. Ongoing instability in Myanmar puts these ventures in jeopardy, and their failure would hand China a decisive advantage in the competition for regional influence. Myanmar’s mineral wealth adds another layer of urgency: access to rare earths, oil and jade is critical for India’s high-tech and defence industries, as highlighted at the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit. Not of less concern for a civilisational power like India is that Myanmar is also a neighbour with whom it shares deep historical and ethnic ties.

Beyond material and civilisational concerns lies the larger geopolitical balance. The deeper China embeds itself in Myanmar, whether through infrastructure projects, naval access in the Bay of Bengal or potential troop deployments, the narrower India’s strategic space becomes in its own neighbourhood where it cultivates hegemonic ambitions.

Finally, there is India’s normative credibility. Having already drawn criticism for endorsing Bangladesh’s widely discredited 2024 elections, India cannot afford to be seen as complicit in Myanmar’s sham polls. By notionally supporting the Bangladesh polls, India signalled that strategic compulsions trump democratic principles. The cost has been reputational. Repeating the same playbook in Myanmar would double the damage. Its image as the world’s largest democracy and as a normative power leading the Global South depends on striking the right balance between hard strategic interests and principled commitments.

So far, India has adopted its well-honed policy of strategic ambiguity. Faced with a web of interests, it has maintained lines of communication, overt and covert, with both the junta and the resistance, while resisting western calls to isolate the regime. India’s approach has been one of calibrated neutrality, publicly avoiding entanglement but privately ensuring that its core interests are protected. This balancing act has preserved room for manoeuvre. In doing so, the mandarins in India’s foreign office have echoed the diplomatic dexterity for which Indian foreign policy was once renowned. However, the approaching election, however farcical, will test the limits of this strategy.

India’s stakes in Myanmar are far too significant to be gambled on short-term political shifts. Until the country finds its way back to stability, New Delhi must remain steady, patient and always mindful of the high costs of miscalculation.

—The author is a strategic consulting and national security expert, and a governing body member of SHARE (Society to Harmonise Aspirations for Responsible Engagement).