Teng Biao was born in the small village of Xiaochengzi in northeast China, where he lived a frugal life―financially and intellectually―until he joined Peking University in Beijing at the age of 18. The university threw open before him new avenues and ideas and he was fascinated by the concepts of human rights and liberal democracy. Teng was excited to read books that spoke unabashedly about ideas which were alien to him during his growing up years under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party.

Teng joined Peking University in 1991, two years after the Tiananmen Square protests. That summer witnessed a series of geopolitical upheavals which altered the existing global order beyond recognition. The fall of the Berlin wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union and its east European satellites brought a surge of democratic spirit to large swathes of Asia and Europe. Although the CCP stood unwaveringly firm, the global churn saw the rise of human rights activism in China as well.

“In the early 2000s, I was one of the initial promoters of the humanitarian movement in China. It was called the Rights Defence Movement, which succeeded the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement in 1989, in which Chinese citizens asserted their constitutional rights through legal means,’’ said Teng. “Finally, my passport was seized. I was kidnapped and tortured thrice―in 2007, 2011 and 2012.’’

Teng was banned from teaching at the Beijing-based China University of Political Science and Law and was disbarred from practising as a lawyer as well. He left China via Hong Kong in 2014 when he got an invitation from the Harvard Law School. He made the United States his base so that he could work closely with human rights activists across the world, especially within China. “After I came to the US, I kept regular contact with Chinese lawyers and activists. They have definitely grown in number, but their activities are closely monitored by the authorities. They even face imprisonment sometimes, so it is not possible for them to organise influential activities like the ongoing protests in China,’’ said Teng.

Teng is one of the leaders of human rights movement in China, a tough task as the CCP continues to exercise near total control over the destiny of the Chinese people. Yet, the recent outbreak of protests in multiple cities where people could be seen shouting slogans about freedom has come as a clear break from the past. University campuses across the country have become the nerve centres of such protests, which have been triggered largely by the pent up anger against the stringent zero-Covid policy. People are clearly fed up with rigorous medical tests, isolated life and lonely deaths.

The fresh wave of protests has transcended continental and oceanic boundaries and has struck a chord with young people across the world, especially the Chinese diaspora. The Tiananmen protests were limited to China as the news did not spread far and wide in the absence of the internet. But now, the young and open-minded students, academics and pro-democracy citizens have acquired the technical skill-sets needed to break open the great firewall of China to look beyond and participate in activities happening around the world through social media and internet platforms. China’s market economy is marching ahead and so are opportunities for events, travel and social mobilisation.

Activists in China are joined by large sections of the Chinese diaspora living in the US, Europe, Taiwan and the Indo-Pacific region. They are inspired by the fact that those living inside China are raising their voice. Interestingly, they were challenged in some places by pro-CCP protesters, but they were much smaller in number. According to rough estimates, around 25 protest events have been held so far in the US alone, in major cities and universities in New York, Los Angeles and Washington, DC.

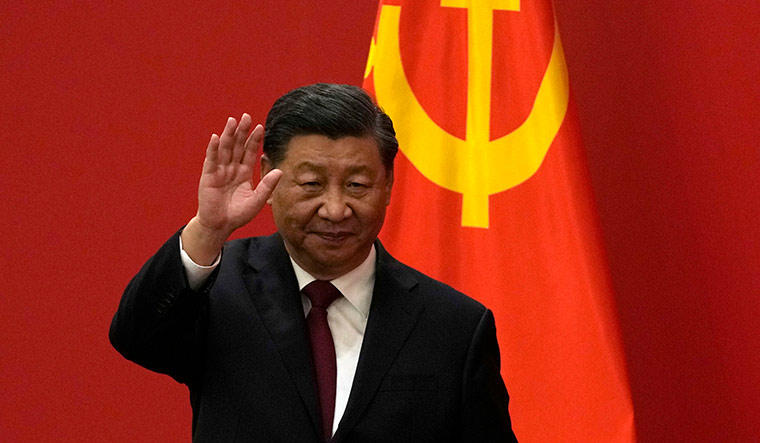

While the protests in China are mainly against Covid restrictions, demonstrations in the US target President Xi Jinping and the CCP. The protesters, both within and outside China, have been closely following Xi’s ascendency to absolute power, as he won a third term as China’s supreme leader at the 20th National Congress of the CCP which concluded on October 22. They were hoping that Xi would offer a gift after the party congress by lifting Covid-related restrictions. But on November 11, China’s National Health Commission released a list of 20 measures to optimise epidemic prevention, leading to widespread disappointment and frustration as it implied continued restrictions. It created discontent as people started writing open letters and began holding demonstrations.

The tipping point was perhaps the fire that broke out in an apartment block in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, the province which is home to the repressed Uyghur ethnic minority. As Covid restrictions delayed rescue operations, at least ten people lost their lives. Protests soon broke out in many parts of China, including in Shanghai where a police crackdown led to further escalation. Tashken Davlet, outreach specialist of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) based in Washington, DC, said the excessive lockdown under the zero-Covid policy had made the Chinese people miserable. “Hearing the CCP’s discriminatory treatment of Uyghurs has made overseas Uyghurs worry that the lockdown will become a new apparatus of genocide, a new way to murder them en masse by starvation,” Davlet said.

But Xi’s challenges are even beyond Urumqi. In the last one month alone, there has been labour unrest in the central Chinese city of Zhengzhou―the location of the world’s largest iPhone plant―while mass protests were reported from Beijing, Guangzhou, Chengdu and Wuhan.

There is, however, scepticism that despite the intensity and the widespread nature of the protests, they may fizzle out after a while, especially after some restrictions are lifted. “When I heard about student protests at Tiananmen 33 years ago, I thought China would change,” said Tashi Tsering, executive director of the Human Rights Network for Tibet and Taiwan. “I was beaten up and jailed. But the CCP has only become stronger.’’

The activists, however, have not given up hope. “I have seen the violent nature of the regime, and the mockery against the Hong Kong democracy movement by many Chinese people,’’ said Terence Law, former vice president of the students’ union of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Yet, as a human being, it is hard to remain silent while watching people stand up for freedom and fight against tyranny, ignoring concerns about their safety.’’