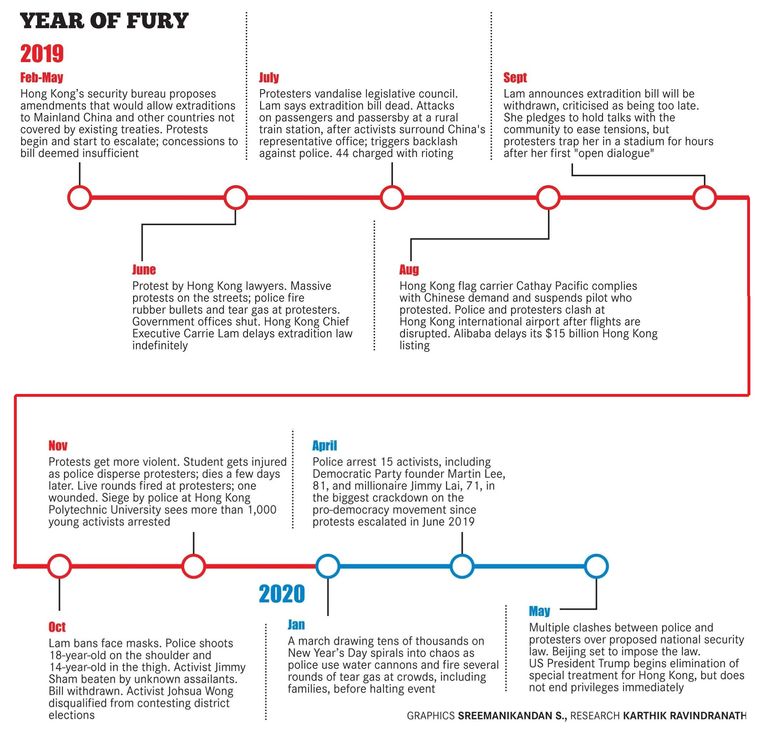

The long,sweltering summer of 2019 will be etched in Hong Kong’s history for the city’s biggest political crisis in decades. Choked by billowing clouds of teargas, gridlocked traffic, scathing slogans and burning barricades, the streets in Hong Kong saw a face-off between two million protestors and the police for over six months.

What started on June 9, 2019, as a peaceful mass protest against a now-revoked extradition bill has now evolved into a “fight for independence”. More than two decades after the end of the British colonial rule in Hong Kong, the Chinese government is all set to impose a new national security law in the city, essentially aimed at criminalising dissent.

As of now, the details of the proposed law have not been made public, but Hong Kongers are getting anxious about losing civil liberties like freedom of expression and an independent judiciary. “It is clear that the manner in which Beijing is going about implementing this law—by going above the heads of Hong Kong’s duly elected legislature and imposing the law by fiat—is a serious blow to Hong Kong’s rule of law and autonomy under the ‘one country, two systems’ formula,” says Antony Dapiran, a lawyer and author, who has documented the city’s protest culture in his two books, City of Protest (2017) and City on Fire (2020).

Originally from Australia, Dapiran has been living in Hong Kong for the last 20 years. He feels the biggest change in the city has been an increasing influence of China over everything—be it business, tourism, traffic or simply the number of Mandarin Chinese on the streets. “Everyone expected that the ‘two systems’ would converge into the ‘one country’ by 2047, when the 50-year guarantee of Hong Kong’s autonomy expires,” he says. “I think what has changed is how much more quickly than everyone expected that convergence is coming, and also that the ‘one country’ Hong Kong is converging with is looking less liberal and more authoritarian than at any time in the past 20 years.”

Located at the crossroads of the east and the west, Hong Kong transformed into a truly global city with buzzing financial districts and cultural hotspots over the past five decades. Its special status under the ‘one country, two systems’ policy promised freedom of speech, independent financial institutions and a fully convertible currency. Since 1997, more than a million people from the mainland have moved to Hong Kong in search of a brighter future in a socially and politically liberated environment. However, China’s recent overreach and the growing insecurities of the locals have left a deep impact on the migrants in the city. “I moved here nine years ago because the city really excited me. It was more open, modern and inclusive than China. However, in recent years, I have been seeing tribalism and identity politics taking over the city’s inclusive spirit,” says Tracey Wong, an entrepreneur and wine writer. “Some of the restaurants in the city have stopped serving people like me who speak Mandarin. The agitation is getting extreme. Hong Kong was never promised independence, it was promised a high degree of autonomy. I think it is very clear that the government would preserve the ‘one country, two systems’ principle.”

The growing identity crisis and unrest among the youth in Hong Kong have been brewing for years now. It all started with some wealthy Chinese investing in the city’s real estate business in the 1990s, which propelled Hong Kong’s rise as a financial and trade centre. This drove up the cost of living for the educated, white collar professionals in the city and a struggle for jobs, housing and education soon ensued. According to Dapiran, there are clearly deep issues of identity tied up in the protest movement. “Beijing’s overreach tends to drive the anxieties which feed into making this identity even more entrenched,” he says.

While Hong Kong has had a long tradition of peaceful marches, the newer generation is more confrontational in its approach. They are ready to clash with the police and even set universities on fire. “The 2019 protests had a number of hallmarks—one was the ‘leaderless’ nature of the protests and their ‘be water’ philosophy, which made the movement a very fluid, and very resilient, phenomenon,” explains Dapiran. “The second was the broad degree of community support, and the solidarity behind the ‘no splitting’ principle, which meant that people remained unified behind the movement as a whole, notwithstanding the more extreme nature of certain elements within the overall movement.”

The most widespread expression of public anger with Beijing in recent years, last year’s protests have left a deep impact on the city. While the outbreak of Covid-19 paused the demonstrations for a few months, activists are now planning a full calendar of protests and mass movements. The police, too, is ready for a clampdown under the command of a new chief appointed by Beijing. Armed with water cannons and pepper sprays, anti-riot officers can be seen at most protest assemblies across the city. “Around 9,000 people have been arrested in the last one year, the youngest one being just 11. The government needs to intervene and stop police brutality. We will not forgive or forget these attacks,” says Daniel Chan, an activist who is majoring in music at one of the leading universities in Hong Kong. “The students are frustrated for various reasons. The government barred our leader, Joshua Wong, from running in the local district council elections last year. And now Beijing wants to force a new national security law upon us. This will be the end of Hong Kong. Our demands are very clear and the protests will go on,” he says.

According to political observers, Beijing’s latest move to tighten its grip on Hong Kong should not come as a surprise. “China has been giving these signals for over five years now. The city’s chief executive has not been able to maintain the law and order situation as desired by the central government, so they are now coming up with the national security law,” says Thomas Abraham, adjunct professor at the University of Hong Kong and former editor, South China Morning Post.

While Hong Kong’s campaign for democracy was always a long shot, China’s direct intervention is being seen as an attack on not just citizens’ rights, but also on their distinct identity. “China has never been able to reconcile Hong Kong to be Chinese and that is a major sore point. Ironically, it shows that the ‘two systems’ theory works. China’s dilemma now is how far these two systems will diverge and still be one country,” says Abraham. “When Hong Kong questions the national security law, China feels it is going beyond the ‘one country’ notion, whereas Hong Kong is well within its rights to protect its freedom. The next significant moment in the city will be when the university campuses reopen. The protests will get a new momentum then.”

The political deadlock, months of civil unrest and the pandemic have ravaged Hong Kong’s economy. In the first quarter of this year, the city’s economy plunged 8.9 per cent year on year, the steepest quarterly drop in the past four decades. So far, the biggest strain has been felt by retailers, hotels and restaurants. “We cater to hotels and restaurants in the Kowloon and Hong Kong island region, which have been protest hubs. In terms of volume, our flagship brand, Les Jamelles, is a leading brand in Hong Kong,” says Olivier Hui-Bon-Hoa, regional director-Asia at winemakers Badet Clément. “Last year, in Q1, Q2 and Q3 we were at 12 per cent growth, but we closed the year at 7 per cent. We have not seen such a drop in the last 10 years,” he says.

For Sonia Hamera, an Indian expat in Hong Kong, the idea of having ‘no democracy’ does seem scary. “Our business is mainly based out of China, and it has been difficult to keep operations smooth with the travel ban. The notion of one country, two systems is gradually fading,” says Hamera, who has been living in Hong Kong for over 20 years.

The political upheaval in Hong Kong has left an indelible mark on the psyche of even those who are not directly connected to the protests. A heightened sense of helplessness and fear has torn the city’s social fabric. Many parents, for instance, have kicked out their children over political disagreements. “I work in a university, so I have been in touch with a lot of young people who are frontline protestors. I feel stressed and a bit hopeless about how Hong Kong can still continue to thrive. While the older generation understands the context of the Hong Kong-China relationship and has accepted the constraints, the youth wants to take charge and fight for freedom,” says Wills Li, a manager at one of the leading universities in the city.

The protests in Hong Kong are unlikely to cease anytime soon. Many activists have pinned their hopes on the pressure being exerted by the US, but it has not undermined the strength of the Chinese government in any way. “Several years from now, it may look like our protests failed, but this last year has proved to be a touchstone that feeds the continuous demands for democracy,” says Chan. “It is a long game, and we will never surrender.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities.