Bats did not bring Covid-19 to Brazil, the deadly virus came through the noses, lungs and throats of revellers eager for the Carnival. It was carried by upper-class Brazilians who had the means to escape to Milan, Aspen or Rome during the world’s biggest street festival. The arrival of the virus was not a surprise as we watched the news from Wuhan and YouTube videos of abandoned Italian streets, wondering if local governments would cancel the Carnival this year. They did not, and this country of 211 million saw more than 27 million people, from across Brazil and the world, take to its packed streets for seven days. And that is how Brazil, now projected to be the epicentre of the pandemic, became our collective nightmare. Added to the challenges every country is facing with lockdowns, illness, death and economic collapse, Covid-19 has thrown us off a cliff and into the chasm that is Brazil’s great social, economic and racial divide—our peculiar brand of tropical apartheid.

I am not Brazilian. I am an African American singer who fell in love with this amazing country and moved here two decades ago. I live in what many refer to as “Black Rome”, the city of Salvador in the state of Bahia. Brazil received 40 per cent of all Africans who were enslaved and shipped as cargo to North America, the Caribbean and South America to provide the free labour that created great wealth for European merchants and nobles. This, unfortunately, is the story of the whole “New World”.

As Brazil’s first capital, Salvador and the surrounding rich farmland received huge numbers of enslaved Africans. Today, their descendants make up roughly 82 per cent of the city’s population, while the national average is 56 per cent. Most of them live in poverty, and they are seeing the highest mortality rates. Covid-19 has no racial or economic divide. There is simply the opportunity for transmission and infection in the midst of poverty, malnutrition, dense population and lack of sanitation.

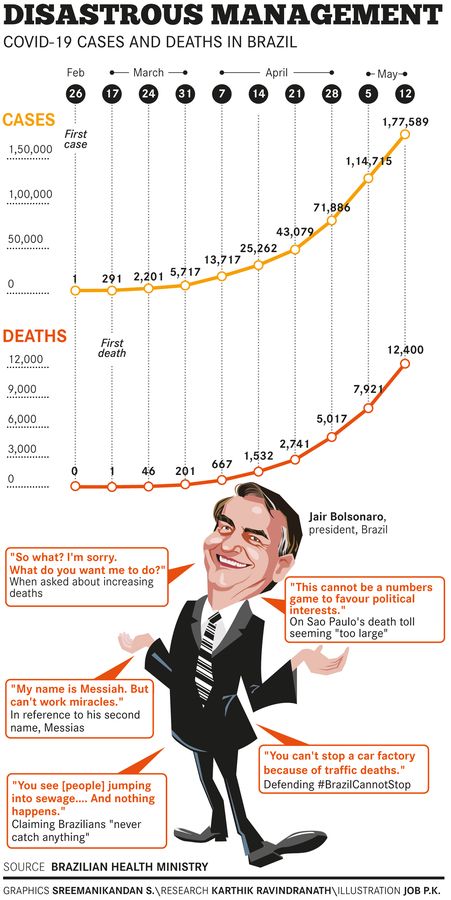

As of May 11, the Brazilian ministry of health has reported 1,62,699 confirmed cases of Covid-19 with 10,627 deaths. But researchers say the actual numbers will be 12-15 times higher. The Brazilian public health system has 2.62 beds for every one lakh inhabitants. Most of the beds are in the big cities, leaving the countryside at a big risk. Last week saw a 22 per cent increase in deaths and if the numbers continue to rise, the pandemic will break the national health care system, which is used mostly by poor Brazilians. “As the virus spreads to the outlying, poorer regions, the death rate will be much higher because it is going to join other epidemics like dengue fever and chikungunya and conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes and malnutrition. Putting all these together, you can see the situation of the poor, black population,” says Silvio Humberto, city councilman in Salvador, and professor of economics at the State University of Feira de Santana. “Covid-19 has come to make a grave situation of social vulnerability worse. The city of Salvador is cited in poetry and prose for its enchantment and physical beauty. But the pandemic has come to show us that Salvador has gained the title, not of the city of music, but of the city of the poor.”

Slavery in Brazil lasted from the 1530s till May 14, 1888. But after their emancipation, the victims of slavery were left to fend for themselves by doing precarious, informal work, such as sharecropping or hard labour. At the same time, European immigrants were offered land and free passage in exchange for agricultural work. The result is that the south and southeast of Brazil, where the European immigrants settled, became more white, accumulating and distributing more wealth, while the north and northeast continued to be locked in a slavocracy with most of the land owned and controlled by descendants of the beneficiaries of the Portuguese land grants who maintained the racial, class and economic disparities of slavery. Humberto says the virus has only revealed the tip of the iceberg. “We had poverty, informal labour and people scraping for a living doing whatever they could in the streets, doing their hustle. Families sustained themselves this way. Now the streets are closed off,” he says.

Doranei Alves, an Afro-Brazilian social worker who lives in Salvador’s São Caetano neighbourhood, says the situation is dire. “There is a huge street fair where everything—from shoes to tea and natural herbs to fruits—is sold. Imagine what is happening to the people who make their living from this. This money pays for their food each day. With the pandemic, everything has stopped. The media says ‘stay home and use a mask’. But people need to eat. Money from the government is taking a long time to come. Many people have not gotten it yet.”

As a musician who is out of work because of the lockdown, I am not rich by any means. But the fact that I can stay home, alone, and live on money I have saved means that I am privileged. In many communities, people are weighing the risk of getting infected against the need to feed their children. “People cannot afford to stay at home anymore,” says Alves. “They have returned to street fairs and have started selling their products again. This reveals how much inequality is there in Brazil. Mothers go crazy when there is no food for their children.”

The combination of financial, mental and emotional stress has led to increased domestic violence and also defiance that contributes to the spread of the virus. “Women are going crazy because of domestic violence. This affects children and their development,” says Alves. “Many old people are at home alone. Family members used to visit them every day and now they cannot visit. Physical contact is very important. It is hard when you are deprived of it.”

While the fear of getting sick has forced many people to comply with the norms of social distancing, others are rebelling, following the example of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro. “There is a group that defends the president and the majority of them are men,” says Alves. “They are using the president as an example and are going against the recommendations. These men are going to play football, even though they know that they are putting their families at risk. They are going to bars. They are trying to show defiance through their actions. The fight against the virus is also an ideological and political fight.”

Bolsonaro, however, insists that Covid-19 is just a cold and says Brazilians could “swim in excrement and still emerge unscathed”. He says his priority is the Brazilian economy, not Brazilian lives. He questions scientists who oppose his opinions, rails at the press coverage of the pandemic and refuses to wear a mask even at rallies where he shakes hands and hugs his supporters. He even planned a big barbecue at the presidential palace on the day when deaths from the pandemic crossed 10,000 in Brazil. It was cancelled finally following widespread protests and the threat of a lawsuit.

For Bolsonaro, the pandemic has provided a convenient cover for rolling back land rights of indigenous peoples and Afro-Brazilian quilombos—homesteads where descendants of escaped slaves and indigenous people have lived for hundreds of years. Decree MP910 signed by Bolsanaro is before the Congress, and once approved, it will allow loggers, wildcat miners and farmers to lay claim to protected land reserves in the Amazon, traditionally inhabited by indigenous Brazilians. It has emboldened them to invade land and kill indigenous leaders even as they spread Covid-19 among indigenous people with no immunity or access to hospitals. Ivaneida Bandeira of the NGO Kanindé says the pandemic is being used as a cover by the president and corporations involved in agro-business, logging and mining.

Humberto, however, sees an opportunity for change in the ongoing crisis. “With so much uncertainty, we have an opportunity to stir things up,” he says. “We have a non-government. The president goes against science, against the 10,000 deaths. While our country is mourning, the president is jet skiing. This shows how insensitive, ignorant and incompetent the president is. He does not resolve problems, but creates crisis on top of crisis. But the light in this crisis is the empowerment that solidarity has brought to the Afro-Brazilian communities.”

Humberto says there have been numerous examples of solidarity and brotherhood across the country. “The pope was right, there is no salvation individually. Salvation has to be collective and we have to be very careful about returning to the so-called ‘normal’ like it was before,” he says. “We need change, not just in the economy, which has been turned on its head. The economy cannot be the be-all and end-all. It should serve society. We have to be liberated from this hegemony of financial capital. It is going to be difficult, but we cannot keep having money generating more money to the detriment of everything, of the people. The people need to be the beginning, the middle and the end.”

The newfound solidarity has given hope to millions. Marcia Marciel, a social worker from the neighbourhood of São João do Cabrito, says volunteers in the neighbourhood have decided to create a chain of solidarity. “The solidarity has multiplied,” says Marciel. “I hope that this chain will continue to remain even when this is over.”

Alves says there was solidarity when he was growing up. “It is still present, even though today capitalism separates people and encourages individualism. But still, if you need some flour, it is your neighbour who will help you”, she says. “As the wheels of the government turn slowly in response to the pandemic, community organisations are providing for the residents using their own resources and money donated from friends, colleagues and others who feel that we have a shared responsibility to provide for those in need.”

Humberto believes it is going to be a new beginning. “This is not just about Covid,” he says. “It is a vision of an African Utopia, an evolution and a new view.”

The author is an African American singer settled in Brazil.