It is a truth that applies everywhere, but particularly so in totalitarian China, that the personal and the political are inseparable. Jung Chang learned this early. Born in Sichuan in 1952, three years after Mao Zedong founded the People’s Republic of China following the communist victory in the civil war, she grew up watching politics invade the most intimate corners of life. It manifested as starved bodies, dissent being punished with banishment to labour camps, and Mao exalted to the status of a god.

That entanglement of the personal and the political manifested itself even at home as both her parents were members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). “My father joined at 17, and took up work as a shop assistant at a left-wing book shop in 1938,” Chang tells THE WEEK at the Jaipur Literature Festival. His motivation was simple: “At that time, there was terrible corruption, hunger and injustice in China,” she says. “The communists had promised to change that.”

Chang’s mother joined the party even younger, at 16. The appeal was partly political. Chiang Kai-shek’s party Kuomintang, then in power, was “corrupt, incompetent and quite cruel”, Chang recalls. “The communists offered an alternative.” But the appeal was also personal. The party spoke of women’s liberation—a radical idea, especially in a society where Chang’s grandmother had been taken as a concubine by a warlord. She had to endure foot-binding, the brutal practice that deformed girls’ feet in the name of beauty. The communists promised to abolish concubinage altogether.

Chang crystallised these experiences in her seminal 1991 book Wild Swans, a family autobiography that narrates a century of Chinese history through the lives of three generations of women: her grandmother, mother, and herself. Translated into 37 languages and having sold over 10 million copies, it remains the most widely-read English autobiography by a Chinese writer, even as it is banned in China.

Fly, Wild Swans

In 1978, Chang moved to Britain to study, becoming one of the first Chinese students to do so. This was no coincidence. It came two years after Mao’s death and in the year his successor Deng Xiaoping launched sweeping reforms that opened China’s economy and allowed people like Chang to travel abroad.

Wild Swans ends here. Chang resumes the story in her latest book published last year, Fly, Wild Swans, a work still shaped by loss; she has not been able to visit China since 2018. She can only communicate with her mother, who still lives there, over video.

“When I wrote these books, I was always conscious of telling a personal story and keeping the political to a minimum,” says Chang. “But unfortunately, in China, the personal and the political are inseparable, which is still true today. You can’t write a purely personal story without getting into politics.” Her own life, and those of her mother and grandmother, she adds, has been deeply entwined with the social and political upheavals of their time.

A cultural desert

Chang’s own tryst with politics began young, during Mao’s Cultural Revolution when China “was a complete cultural desert”.

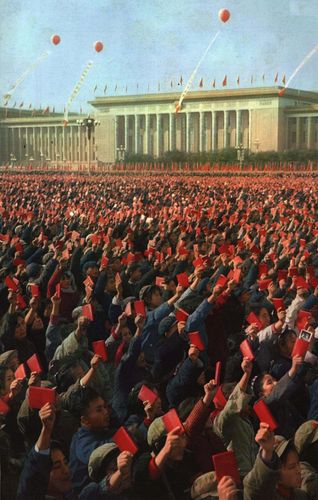

Launched in 1966, the decade-long socio-political movement sought to further Chinese communism by purging bourgeois elements and traditional influences. “There was no normal schooling. Books were burnt. Museums, theatres and cinemas met with the same fate,” Chang says.

While her parents had their own reasons for joining the Chinese Communist Party, Chang herself did not think twice when she joined the Red Guards—the student-led movement mobilised by Mao—at the age of 14. “I grew up under intense brainwashing,” she recalls. “When we were children, if we wanted to say something was absolutely true, we would say, ‘I swear to Chairman Mao.’ Mao was our god. It was like: you must eat food, you must drink water, and you must obey Chairman Mao.”

So when Mao called on the young to join the Red Guards, she did, too. But disillusionment set in quickly. Within two weeks, she quit. “I didn’t like what the Red Guards were doing in my school,” she says. “I hated it when they pulled down these huge tablets of Confucius’s teachings.”

It did not stop there. Red Guards raided people’s homes, carting off books meant for burning. But many books escaped the bonfires and found their way to the black market. Her brother discovered one such market, bought stacks of books and buried them underground. “That’s how I read,” she says. “Foreign and Chinese classics—the books that had survived the Red Guards.”

Fall from privilege

With both her parents being among the Communist Party’s elite, Chang grew up with a degree of privilege. For example, during the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962)—the ambitious campaign to rapidly transform China from an agrarian to an industrial economy—tens of millions died of starvation, but Chang’s family escaped that fate.

“My father was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party,” she recalls. “So we had more food. I remember, as a child, going with my grandmother to special shops to buy a handful of beans.”

That privilege, however, vanished when Chang’s father chose to speak up. During the Cultural Revolution, he wrote to Mao asking him to stop the violence and atrocities. “After that, my family plummeted from privilege into hell,” she says. Her father was arrested and sent to a labour camp, while her mother came under tremendous pressure to denounce him. She refused. “She was extraordinary,” Chang says. “Even though she had bitterness towards my father, she would not denounce him. It is incredible to think that during those 10 years of the Cultural Revolution, so few privileged people escaped denunciation meetings and tragedy.”

Despite the suffering, her parents’ moral resolve left a lasting imprint. “Subconsciously, they became my role models,” Chang says. “They taught me loyalty, courage and love.” It is why, she adds, she never considered giving up writing her books, including a biography of Mao. “I just decided to be an honest writer. That, I think, is my parents’ influence,” she says.

When Mao died

And on September 9, 1976, Mao died, aged 82. “I was at university,” Chang recalls. “Everyone burst into tears. I, however, was dry-eyed. By then, my father and grandmother had died. I had shed all my tears and was left with none for Mao.” But being dry-eyed, she knew, was dangerous. So she put her head on the shoulder of the girl sitting in front of her and pretended to cry. “People even suggested rubbing peppers into your eyes,” she recalls.

Soon after, the father of Chinese communism was replaced by the architect of modern China, Deng Xiaoping, who emerged as the country’s paramount leader in 1978. His rise marked a turning point: China began opening up to the world.

Moving to Britain, landing on Mars

Chang describes her arrival in Britain as “landing on Mars”. “I had never spoken to a foreigner, except for a few sailors at south China ports, where, as an English student, I was sent to practise my English,” she recalls. However, it did not take long to realise that, at their core, these ‘foreigners’ were the same as her and other Chinese.

Yet, being abroad did not mean complete freedom. “We came in a group of 14. One of us was the political supervisor. We weren’t allowed to go out on our own and had to move as a group. And we all wore Mao suits,” she recalls.

The write move

By the mid-1980s, Chang became the first person from communist China to earn a PhD from a British university. She did not set out to write Wild Swans. It was not until 1991 that her first book was published. “At first, I did not want to write,” she says. “Writing meant looking inward and into the past, and the past was full of tragedy. I wanted to forget it all.” That changed in 1988, when her mother came to stay with her in London. During the six-month visit, her mother began recounting stories of her life, as well as those of Chang’s father and grandmother. “She had so much to say,” Chang recalls. “I bought a tape recorder, and she would talk into it while I was out at work.” By the time her mother left, Chang had amassed nearly 60 hours of recording. She sat down and transcribed them, and that’s how Wild Swans began. Since then, Chang has published several works, including Mao: The Unknown Story (2005), Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (2013), Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister (2019), and Fly, Wild Swans. Her books remain banned in China.

President Xi Jinping, Chang says, is “a true believer in Mao”. While China has changed dramatically since 1978, she argues that its political core has not. “It rejected the worst excesses of Maoism after the reforms,” she says. “But Mao is now being resurrected, and the parts that are anti-culture, harsh and repressive—those have not changed.”