When I sit down to chat with author-journalist Aatish Taseer about his new book, A Return to Self: Excursions in Exile, I tell him that when I first picked it up, I expected to find little relatability to it. The son of an Indian journalist and a Pakistani politician who was assassinated in 2011 for defending a Christian woman accused of blasphemy, Taseer had his Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) card revoked in 2019. While he maintains that it was because of a story he wrote for TIME magazine in 2019 with Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the cover, titled ‘India’s Divider in Chief’, the government argues it was because he concealed the Pakistani origins of his father.

“To lose one’s country is to know an intimate shame, like being disowned by a parent, turned out of one’s home,” Taseer writes at the start of A Return to Self. “Your country is so bound up with your sense of self that you do not realise what a ballast it has been until it is gone. It is one of the few things we are allowed to take for granted, and it is the basis of our curiosity about other places.”

This might stoke little relatability, at first, in somebody like me, privileged in every social context in India apart from perhaps gender, but as you delve deeper, layers to one’s identity unfold: sometimes in tandem, and sometimes in contrast, to one another.

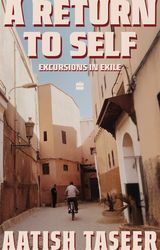

A Return to Self is a travelogue about Taseer’s journey through six years of exile spanning 40,000 miles, across Turkey, Morocco, Mexico, Bolivia, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Sri Lanka, Spain and Iraq, where he delves into the idea of identity through examples such as the Muslim Spain, and the socialist Uzbekistan, among others.

Is Taseer projecting himself as a world citizen?

“No, I don’t like the connotation of a world citizen, because it implies somebody hanging out in Dubai or Singapore and going on holiday in London. This book is a little deeper than that,” he tells me over Zoom from New York, where he is based. The idea of home is mentioned quite often in the book, and “home has always been India”, says Taseer.

In an interview with THE WEEK, Taseer talks about his journey or “pilgrimage”, his latest book, and politics in India and the US.

Q. Your book is titled A Return to Self: Excursions in Exile. You were a British citizen by birth and an American now. How is this an exile?

A. It is an exile in the sense that I can’t come back home, which has always been obviously India. These pieces of paper hold tremendous importance, but that is not how anybody’s sense of self is ever formed. My friend—writer Karan Mahajan—and I used to talk about liminality. And suddenly, those conversations evaporated for me because the finality of not being able to come home was something completely different. It is one of those things you think should not matter, but actually does.

Q. About your exile, you write: “I felt relief. The burden of trying to fit into India, forever apologising for its shortcomings, apologising for my own westernisation was suddenly lifted off me.” Has India always remained the same, no matter which party has been in power?

A. There are certain continuities and aspects in society that are so deep that they don’t change that quickly. And there is complexity to this emotion, because there are so many things about home—it is oppressive and is to be taken for granted. But at the same time, it is home—it is fundamental, it is grounding, and it is from where you chart your distances. And when that—the place you began from—is taken away, there is a great sense of loss and a loss of self, on the one hand, but there is also this feeling: you feel light and free from the pressures of home.

Q. What have your views been about the BJP before it came to power in 2014, and 11 years into its rule?

A. I was very much formed in the crucible of the world of the Congress, and I was critical of them, and to some extent, still am. I felt that they let distances and cultural irrelevancy develop. They were not equipped to be able to speak to the country any more. And the fraudulence, in some ways, of the party is never made more real than by the fact that when you lose an election, in a normal democracy, you put forward a new candidate. You don’t just keep coming back with the same candidate and expect the electorate to change its mind. So what Modi did was that he exposed flaws in the status quo. And we say here about [President Donald] Trump that he is the wrong answer to the right question, and you get that feeling with Modi, too.

And the emotions that propelled me—the hopes and aspirations people invested in him—(and I covered those elections from the ground) were so moving that I did not want to be apart from that emotion. Perhaps it was a lesson for me as a writer that it is quite dangerous to partake in a group emotion, and at the same time, it is so seductive.

Q. How was your relationship with your father, the late Salman Taseer, the former governor of Pakistan’s Punjab province?

A. It was a very bad relationship. He was very domineering, and after having been absent from my life, he suddenly arrived as a tyrannical figure telling me what I could write and what I couldn’t.

I also found him full of revolting prejudices when it came to Jews, homosexuals, and Hindus. My mother had fed me on the romance of the man, but to me, he was a kind of banal, tiresome figure, somewhere between [former Italian prime minister Silvio] Berlusconi and Trump.

Q. Through your journey, did any place feel like home?

A. I was in Mexico City and there was this feeling about these residential streets that felt like I was in Delhi or Lahore. But home was not the central impression, because home is home because it can be oppressive. It is like family. You care much more about it. And I think it is fitting that one should be able to hate home like you hate your family, because it is that much of a deeper emotional investment.

Q. While you could not visit India, Pakistan is also absent from your book.

A. Pakistan is nothing to me. I was always appalled by the fact of it being a historical deformity.

Q. Your OCI revocation has been talked about much. Have you come across similar cases?

A. There have been many cases. They have done this to about 150 people, and in far more transparent ways. [Swedish academic] Ashok Swain is the most powerful example, because he actually won his court case. Then he got his OCI back, but the government put a travel ban on him. I was, rather, a test case that they wanted to see if they could do this to. Many people across the Assam-Bangladesh border are facing a similar situation. India was divided on religious lines, which should not have happened. And what it needs is a leader who understands that our only hope is to soften or undo the legacy of partition, not to entrench ourselves deeper, because there is no future that way.

Q. What kind of conversations were happening around you during Operation Sindoor, and the escalated conflict between India and Pakistan?

A. I fell out with my sister over the war. She was accusing me of nationalism. It was so jingoistic. I am very much in sympathy with the fundamental Indian position that Pakistan has a way of making terror seem like weather. But if it were the reverse, if they were routinely subjected to waves of Indian terror, no country would have supported that.

Q. This year, we have also seen the rise of New York City mayor candidate Zohran Mamdani, a South Asian voice, in the US. How important has been his election win?

A. It is terribly important. But I think it could be destructive politically. I am not a fan of Islam in politics, and I don’t like socialism. I come from a country that was destroyed by socialism. And he is going to be portrayed in a very important election cycle next year as the face of the Democratic Party. But what we need is somebody who can confront Trump on his own terms. So the worst thing that can happen is that the party starts to see him as more marginalised.

It boils down to the fact that in this country, with the Republicans, you have this lunatic electorate and a very sober donor class, and with the Democrats, you have a very sober electorate and a lunatic donor class. The Democrats think that when Republicans elect a nut-case, they have the same luxury. They don’t have that luxury. They have to constantly prove things that the Republicans don’t have to prove.

Q. You say your OCI revocation happened because of the TIME piece. How do you view reporting on India from within the country and from outside?

A. You have seen how ridiculous our media has become. During the Pakistan conflict, it was a horrendous indictment. And there are some things the west can never get right about India. I think people like me have a distinct advantage, because we are balancing certain global realities with what is happening inside India. But those voices are increasingly under threat or have been silenced.

Q. If you had to write the TIME article all over again, how would you approach it?

A. I would improve it, maybe.

A RETURN TO SELF: EXCURSIONS IN EXILE

By Aatish Taseer

Published by HarperCollins

Price Rs499; pages 216