A response by a man from Tripura especially struck writer-historian Sam Dalrymple while documenting oral histories on the partition. “When I asked him about the partition, he said: ‘Which one? There is the partition of 1937, separating Burma from the Indian empire; then in 1947, separating Pakistan, and then 1971, which saw the birth of Bangladesh but also an influx of refugees into Tripura.’ And that got me thinking: What did the [British] Raj actually look like?” he tells The WEEK.

That is exactly what Sam, son of acclaimed historian William Dalrymple, explores in his debut book, Shattered Lands, which looks at the actual expanse of the Indian empire, stretching from Aden to Burma. While the man from Tripura knew of three partitions, there were five that undid the Raj in less than half a century and led to 12 modern nations taking shape—Burma (Myanmar), Nepal, Bhutan, Yemen, Oman, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait, apart from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

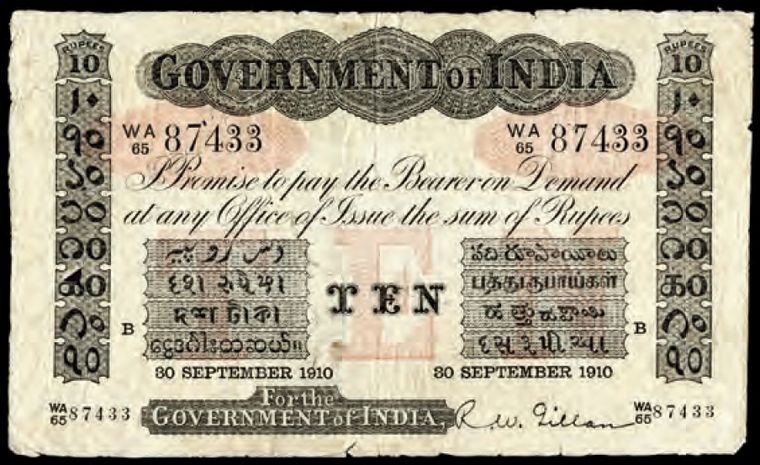

While the expanse of British India is striking in itself, reading about the region’s interconnectedness often leaves you wide-eyed with wonder. Imagine a world where the Arab elite studied in colleges and universities of Aligarh or Bombay, and wore Indian-style sherwanis. Aden, the Indian empire’s westernmost bastion, like the rest of ‘Indian Arabia’, was governed as part of Bombay Province. And everyone carried Indian currency and passports.

Ask Sam about the revelations that especially struck him, and he says, “The fact that Dubai and Doha would have almost ended up being a part of India or Pakistan is astonishing. Also, the fact that Dubai and Qatar were the lowest-ranking princely states, far below Jaipur, Hyderabad, Kashmir, Tripura and Manipur. But today, Dubai is among the richest places in the world.”

When the British and the Japanese clashed in the simultaneous battles of Imphal and Kohima during World War II, “many of the military generals later to rule Pakistan, like Ayub Khan, were stationed here alongside soldiers like Sam Manekshaw,” writes Sam, relating an interesting anecdote. “In 1944, when Wavell knighted General Slim in the city of Imphal, a young Manekshaw would be one of the two Indian officers decorated at the ceremony. The other was Lieutenant Niazi, the future Pakistani commander who would surrender East Pakistan to Manekshaw’s Indian Army.”

Mahatma Gandhi, writes Sam, was “one of the last people to traverse the vast territory of the Indian empire, from Rangoon to Aden, while it was all still a part of India”. Both Burma and Aden were separated from India in 1937.

In his account, Sam appears to be especially critical of Hindu nationalism, which “was a key driving force in these earlier partitions, envisaging an independent India that resembled the ancient Hindu holy land of Bharat, including neither Burma nor Arabia,” he writes. Sam, however, clarifies that he isn’t critical but has tried highlighting the centrality of the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS and such organisations in all these partitions.

“I think that while the standard Indian history on partition highlights the role of the Congress and the Muslim League, that of Hindu nationalism, which was obviously the counterpart of Muslim nationalism, tends to be brushed over,” he says. “But in recent years, with the rise of the BJP, we are seeing a justly more intense scrutiny and focus on Hindu nationalists during this period. Some amazing work is being done. For example, Abhishek Choudhary’s biography of Atal Bihari Vajpayee sheds light on several aspects of the RSS’s history during the 1930s and 1940s that I hadn’t known.”

Sam says not much is available on the true extent of the Indian empire because the research is happening only now.

“So much of it is new research. Every generation of research has new focus areas, and with the rise of the BJP, the new area that people are researching is how this happened—what is the history of the BJP and the RSS? For example, now there are so many biographies on Savarkar that have hugely contributed to our understanding of him,” he says. Another reason why this history is overlooked is: “With each partition, archives were separated.”

Interestingly, the British themselves downplayed the full reach of the Indian empire, especially the Arabian territories, just like “a jealous sheikh veils his favourite wife”, as one Royal Asiatic Society lecturer quipped, to avoid provoking the Ottomans. However, research in the Gulf states is happening now. “Until recently, it was assumed that many of these states had no written history of pre-oil life because there were not many records kept in the Gulf,” says Sam. “And it is only recently that the scholars have realised that all of their colonial-period history is sitting in the archives of Bombay, and that there is so much research to be done.”

Nonica Datta, who teaches colonial history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, says, “As far as the history of Asia is concerned, we seem to be working with a rather conventional and dated framework. We need to decolonise how we look at the histories of Asia, and rather, see them as connected and shared.”

It is all the more crucial, as the remnants of the past still echo today. “Everything from the conflict in Kashmir, the nuclearisation of south Asia, the insurgencies of Balochistan and northeast India, to the Gulf war and the Rohingya genocide, all have their roots in the fragmentation of the Indian empire,” says Sam.

That is why, this relooking of India’s history and the many partitions makes Shattered Lands an important read.

SHATTERED LANDS: FIVE PARTITIONS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN ASIA

By Sam Dalrymple

Published by Fourth Estate India

Price Rs799; pages 536