This year, Delhi’s fight against pollution has seen everything: Chief Minister Rekha Gupta’s “AQI is a temperature” gaffe, the AAP’s Santa-fainting skit, protesters being sent to police custody, an unsuccessful cloud seeding experiment, talks of AI–enabled pollution management and water sprinkling wherever one looks. Everything—except breathable air.

The air, meanwhile, remains ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’—if not ‘severe’—its smell smoky and taste metallic, with the air quality index (AQI) even hitting the cap of 500, posing a serious health risk.

The BJP government in Delhi had allocated Rs300 crore in the 2025–2026 budget to curb pollution, and had earlier approved a dust-control proposal, which is set to cost Rs2,388 crore over the next decade. This is only the latest in a long line of plans rolled out by successive governments—from expanding metro networks to the more cosmetic odd-even rule under the AAP. Yet little has changed on the ground, prompting a question: Are the solutions part of the problem?

WHICH NUMBER TO TRUST?

There was a time when winter conversations revolved around the chill—how biting it was, but also a reward: a few months meant for being outdoors, exercising, picnicking, breathing easier in an otherwise tropical climate. But that winter no longer exists.

Today, stepping out during these months can itself be a health hazard. The conversations, meanwhile, have shifted—from the chill in the air to the air itself.

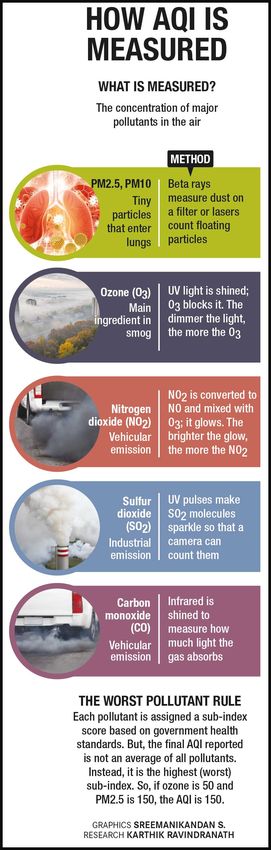

For instance, if you live in Delhi NCR, chances are you check the AQI at least once a day. AQI turns complex data on pollutants like PM2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometres), PM10, ozone and carbon monoxide into a single number and category, making it easy for the public to understand local air quality. What you see, however, depends heavily on which monitor you refer to.

While the Central Pollution Control Board’s (CPCB) data and those of government-backed trackers like SAFAR don’t go beyond 500, private trackers like IQAir often report numbers well above 500, sometimes even breaching 1,000.

This raises questions: Which tracker can one trust? And does India’s official air monitoring truly reflect the health risks its citizens face?

Dr Gufran Beig, chair professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies and founder-director of SAFAR, says that when the AQI grading was introduced in 2014, experts believed that a reading of 500 represented the worst possible air quality. “The idea was to cap it at 500 so as not to panic the public,” he explains. “However, recent evidence shows that... further deterioration in air quality continues to worsen health impacts.”

Manoj Kumar N., an analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), which releases monthly ambient air quality snapshots, highlights why readings differ across trackers. “While the CPCB relies on Beta Attenuation Monitors (BAMs) [which use beta radiation to directly measure particulate matter], private trackers like IQAir use sensors [these use lasers to estimate particle concentration from light scattering], hence the difference,” he says.

Although BAMs are considered more reliable for monitoring, experts say that India’s air quality standards, introduced in 2014, are outdated. “It would be a good practice to measure air quality beyond 500,” notes Kumar, “because pollutants like PM2.5 can harm health even at low concentrations.”

DIFFERING STANDARDS

Notably, India’s air quality standards, too, are lenient when compared globally. For instance, India considers PM2.5 levels up to 60µg/m³ as ‘satisfactory’, a limit four times higher than the World Health Organization’s recommended 15µg/m³.

“The WHO doesn’t provide standards but guidelines based on the latest health research. Every country, meanwhile, formulates and revamps its standards based on its internal data,” explains Beig. One oft-cited justification is that Indians, owing to the tropical climate and other hardships, are supposedly more adaptable.

But the reality is grimmer.

“PM2.5, a major component of air pollution, is classified by the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer as a group 1 carcinogen, especially when it comes to the risk of lung cancer,” says Dr Ankit Jain, senior consultant at Apollo Cancer Centre, Delhi.

In his response in the Rajya Sabha, Minister of State for Environment Kirti Vardhan Singh said that while air pollution is one of the triggers for respiratory illnesses and associated diseases, “there is no conclusive data which establishes a direct correlation between higher AQI levels and lung diseases”.

Jain, however, points out that symptoms of lung or other cancers don’t appear immediately. “It can take 10–15 years for mutations to develop. So while the effects might not be visible now, in the next decade we can expect a surge not just in lung cancer, but also cancers of the head and neck, breast, prostate and bladder, with a direct link to pollution. Chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases will also mushroom,” he says.

According to the data shared by the Union government in Parliament in December, more than two lakh cases of acute respiratory illnesses were recorded in six state-run hospitals in Delhi between 2022 and 2024.

“So if we are really taking our health seriously as a nation, we cannot isolate ourselves by saying that in India this is allowed because we are used to this. I think we have to be stringent with the WHO guidelines,” says Jain.

Meanwhile, Beig argues that while India’s air quality standards need an update, “if you are not even able to comply with the existing standards, why make the stricter ones a priority. Let’s first achieve this and then go on to the next level”.

NOT ENOUGH MONITORS

While Delhi has the highest concentration of air quality monitors in the country, experts say placement matters just as much as numbers. “Readings are naturally higher in densely populated areas; put a monitor in a sparsely populated or peripheral location, and the numbers drop,” says Kumar.

Delhi has 48 air monitoring stations, including 38 Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations (CAAQMS) that provide real-time data. The CPCB sets guidelines for placement, such as at least 20m from trees and 50m from roads or highways, to ensure the data represents the area rather than a single pollution source.

Yet several stations flout these norms. The CAAQMS at ITO sits right beside the road; RK Puram’s station is inside a schoolyard with trees nearby.

Experts also point to a shortage of monitors, despite Delhi’s high concentration. CPCB guidelines call for at least 16 CAAQMS stations in a city of 5 million or more. With a population of 33 million, Delhi lacks 68 stations. Also, monitors are costly. “It can go up to 2 crore per CAAQMS station,” says Kumar.

LOOKING BEYOND DELHI’S BORDERS

While Delhi grabs headlines, NCR cities are just as bad, if not worse. Yet the focus on Delhi lets regional governments escape the scrutiny.

For instance, while Delhi has 38 CAAQMS, Gurugram in Haryana, despite rapid industrialisation and urban expansion, has only four. “Even those are positioned in ways that fail to capture the true picture,” says Arindam Datta, senior fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI).

Similarly, Ghaziabad in Uttar Pradesh has just four monitoring stations; air pollution here frequently reaches hazardous levels as per private trackers. Notably, Ghaziabad was the most-polluted in November, according to CREA’s air quality snapshot for the month.

“Policymakers of Delhi are focused on Delhi. They are not even concerned about what happens in Noida, or Gurugram,” says Beig.

Kumar adds that even if Delhi were to reduce its pollution to zero, the city would still remain polluted. “It is because a large part of it is coming from outside. It is what we call trans-boundary pollution.”

Here, Beig talks about the airshed approach, where a region is defined by common air movement. “Action should be taken within an airshed and not limited to boundaries,” he explains.

A DUSTY ROAD AHEAD

When one looks at the government’s response to tackling air pollution—be it water sprinkling, road sweeping or even cloud seeding—it is primarily aimed at controlling dust. Experts caution that these efforts may be missing the bigger picture. While such measures focus on larger dust particles, or PM10, the far more dangerous PM2.5 remains under-addressed.

“About 68 per cent of the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) funds are being spent to mitigate dust, which is not at all the real solution,” says Kumar.

Beig points out why the focus remains so skewed. “PM10 is a measuring scale under NCAP, so your accountability is fixed to reduce PM10 and not PM2.5. If PM2.5 were the priority, water sprinkling and dust control would be secondary. The real focus would be on transport, biofuels in slums, industries and waste management.”

Even within dust control, the approach is narrow, adds Datta. “Most efforts target dust on the roads. But if you control dust at the source, like construction sites, you wouldn’t need to spend so much on mechanical sweepers and sprinklers,” he says.

COSTLY RAIN

If water sprinkling wasn’t enough, Delhi tried cloud seeding on October 28, hoping that artificial rain could ease the pollution. The trial was conducted by the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kanpur.

Cloud seeding works by releasing particles like silver iodide into clouds to trigger rainfall. This attempt, however, failed due to low moisture levels. The two trials on October 28 cost Rs60 lakh, while the Delhi government has allocated Rs3.21 crore for five such experiments this winter.

“Cloud seeding is an SOS measure—an imperfect solution. It is something we can use when pollution levels are extremely high,” says Manindra Agarwal, director, IIT Kanpur. “It has been very dry this time. The trials, however, have still provided data.”

Moreover, in his reply in Parliament on cloud seeding last year, MoS Singh, citing experts, had expressed reservations around the experiment.

Meanwhile, more cloud seeding trials are in the works in Delhi. “The IMD has predicted low cloud availability at the beginning of January, so we are looking forward to that,” says Agarwal.

TACKLING PROBLEM AT SOURCE

“Tackling pollution at source is the best way,” says Agarwal.

While stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana is routinely blamed for Delhi’s air crisis, experts stress that its impact is limited to a week or two each year. For the rest of the year, the pollution is largely home-grown.

Data backs this up. According to CREA’s monthly air quality snapshot for November, the contribution of stubble burning to Delhi’s pollution fell sharply, from 20 per cent last year to just 7 per cent this November. Yet, “20 of 29 NCR cities recorded higher pollution levels than the previous year,” notes Kumar. “This clearly shows that year-round sources—transport, industry, power plants and other combustion activities are the dominant drivers. Without sector-specific emission cuts, cities will continue to breach air quality standards.”

Transport, in particular, remains a major concern. Delhi has an enormous vehicular load—around 1.2 crore registered vehicles, including nearly 33.8 lakh private cars, according to the Delhi Statistical Handbook 2023.

“You cannot control PM2.5 levels if you ignore the transport sector,” says Datta.

The government has rolled out several measures, such as banning the entry of vehicles not meeting the Bharat Stage VI (BS-VI) emission standards from outside Delhi and making Pollution Under Control Certificates mandatory for refuelling. However, experts argue that these steps are undermined by the sheer scale of vehicular growth.

“Say, Delhi had one lakh BS-IV vehicles in 2018. Now, even if the vehicles are BS-VI-compliant, the total number has doubled,” Datta explains. “So while emissions per vehicle may have come down, the number of pollution sources has gone up. That’s where the problem lies.”

Then there is industrial pollution. “Polluting industries are required to report their emissions to the CPCB or the respective state pollution control boards. So the data already exists, and authorities know which industries are polluting,” says Kumar. “We also know which ones fall under the red category—power plants, steel plants and the like. If strong action is taken against these sectors, it can have a significant impact on pollution levels across the country.”

NO LONGER A DELHI PROBLEM

While attention continues to centre on Delhi-NCR, air pollution is increasingly a pan-India problem.

Despite being geographically better placed than Delhi, Kolkata frequently ranks among the world’s 10 most polluted cities, according to IQAir. And in its 2024 report, Byrnihat, a small industrial town on the Assam–Meghalaya border, was named the most polluted city globally.

Other metros such as Mumbai and Bengaluru also routinely grapple with toxic air. Beyond cities, the situation is no better. A recent study published in Environmental Science & Technology found that residents in Bihar breathe unhealthy air on nearly 90 per cent of days during the post-monsoon and winter months.

The findings make one thing clear: air pollution is no longer just Delhi’s problem. And, as experts repeatedly stress, tackling it at the source may be the only way forward.