Twenty-eight years is a lifetime in public policy. It is long enough to build institutions, correct mistakes and ensure that a tragedy never repeats. But in India, the Uphaar Cinema fire of 1997, which took 59 lives, has aged only in memory, no lessons learned. From a packed cinema hall in South Delhi to a crowded nightclub in Goa, the script remains eerily similar—illegal structures, missing fire clearances, blocked exits, delayed emergency response and promises made after tragedy.

What sets Uphaar apart is not just the magnitude of the tragedy, but the doggedness of those who would not let the system forget. After years of litigation, the Supreme Court in 2015 imposed a 60 crore fine on the Ansal brothers—Sushil and Gopal—who owned the cinema. The court directed that the money be used to create a trauma centre in Delhi. The logic was simple—had emergency trauma care been swift and specialised, many lives could have been saved.

After a decade of what looked like inaction, the Association of Victims of Uphaar Tragedy (AVUT) approached the apex court again. But, the Delhi government informed the bench it had already fulfilled the spirit of the order by setting up three hospitals. Its affidavit said the money, meant for a trauma centre in Dwarka, was spent on facilities at the Sanjay Gandhi Memorial Hospital in Mangolpuri, the Satyawadi Raja Harish Chander Hospital in Narela and the Siraspur Hospital. However, none of these hospitals is operational today.

Moreover, AVUT argued, none of them was a trauma centre. AVUT representative Neelam Krishnamoorthy told THE WEEK that a trauma centre was a specialised and time-critical facility. “Trauma centres integrate emergency medicine, surgery, burn care, neurology and rapid transport protocols in a way regular hospitals do not,” she said. “And that’s precisely why AVUT had insisted upon a trauma centre, and not a general hospital.”

During the Uphaar fire, victims were shunted from one hospital to another, wasting precious minutes. The tragedy highlighted how India’s capital lacked an integrated trauma response system. Almost three decades later, it is beside the point for the state to argue that there are hospitals. As AVUT argued in court, availability is not the same as preparedness, and proximity is futile without speed and specialisation.

Neelam’s husband, Shekhar Krishnamoorthy, also highlighted another aspect of the 2015 court order. “Land was supposed to be given by the then Delhi Vidyut Board [for the trauma centre], but it isn’t clear whether the land was given or not,” he said.

Indeed, the way AVUT has been systematically sidelined is telling. While it may have provided the moral and legal impetus behind the case, it was not consulted on the use of funds, nor did it feature in any planning.

For Neelam and Shekhar, who lost their children Unnati and Ujjwal in the fire, the struggle has stretched across 28 years of courtrooms, appeals, diluted sentences and administrative inertia. Justice came slow. Reform not at all.

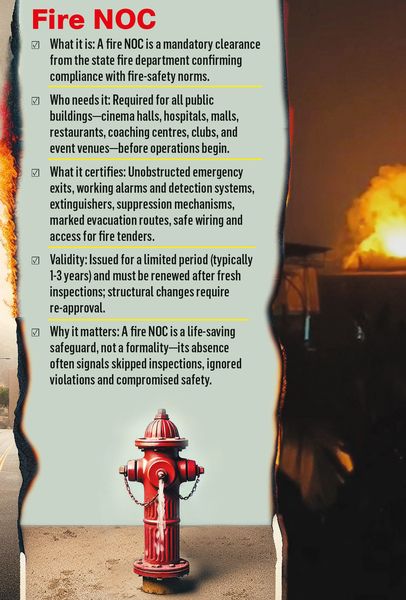

That failure was laid bare in the Goa nightclub fire. The litany of violations revealed by the preliminary investigation—the lack of a valid fire NOC and working fire alarm or suppression system, inadequate emergency exits and escape routes—mark it as a textbook case of regulatory collapse.

To survivors and relatives of victims, the tragedy seems a result of negligence rather than an accident. “My brother worked there,” said Maria Fernandes—he died in the blaze. “He always said the place was overcrowded and unsafe. There were days when exits were blocked with furniture. We complained, but no one listened.” The owners of the club—Luthra brothers, Saurabh and Gaurav—have been arrested and cases registered for culpable negligence.

The Goa government has also ordered a statewide audit of nightclubs, bars and enclosed public venues, and sealed several establishments without valid fire clearances.

Safety activists point to how fire audits are conducted only after tragedies, as routine inspections remain sporadic. “The law is clear,” said a former fire safety official, who requested anonymity. “But enforcement is weak. Licences are renewed mechanically and violations overlooked until lives are lost.”

The relatives of the deceased said accountability should go beyond the venue owners. As the mourning continues in Goa, this fire has reopened an uncomfortable national conversation about public safety in places of entertainment. About the pattern: rules exist, warnings are ignored and compliance is enforced only after tragedy strikes.

To the families, justice will be more than arrests; it will mean a guarantee that no other evening of fun will result in death.

“Every time a tragedy of this nature occurs, I relive everything all over again,” said Neelam. “When we launched this fight, it was never only about justice for our children. It was to ensure no other parent loses a child simply because somebody decided to compromise on safety laws. No parent deserves to get their child’s body because they went out to watch a film or went out for an evening. I know the pain of living without your children.”

She added that they believed that if they could prevent even one such tragedy from occurring, it would be a true tribute to their children and a service to society. “We fought relentlessly, and the courts did lay down safety guidelines for cinema halls,” she said. “But my plea has always been that safety cannot stop there. Unfortunately, despite all these years, I feel we have failed in that larger mission. The lessons of Uphaar should have applied to every public space, not just cinemas.”

Fires in hospitals, coaching centres, commercial complexes and residential buildings across India continue to reveal the same truth: fire safety exists largely as paperwork.

After Uphaar, India rewrote building codes, strengthened fire norms and promised stricter inspections. But enforcement was never institutionalised. Fire departments remain understaffed. Inspections are routine rituals. Penalties are negligible. Criminal liability is rare.

Most important, there is no national trauma response framework that integrates fire safety, emergency transport and specialised care.

The Uphaar case also brought into sharp focus how the judicial system struggles to deal with mass negligence. While conviction was secured, sentences were softened progressively. Custodial punishment gave way to fines. Accountability thinned with each appeal. For future violators, the message was unmistakable: compliance is optional, consequences negotiable.

Uphaar should have been India’s fire safety watershed. Instead, it turned out to be a memorial without muscle. Meanwhile, new fires continue to add names to a list that should have frozen in 1997.

As long as trauma centres are substituted with general hospitals, inspections follow funerals and victims have to fight for decades to enforce court orders, tragedies like Goa will not be aberrations.

Twenty-eight years on, Uphaar’s lesson remains painfully intact, waiting for a system willing to finally learn it.