In 2016, BitConnect Coin (BCC) was hailed as the next miracle of the digital age—a cryptocurrency that promised ordinary investors extraordinary returns. The fraud division of the US Department of Justice (DoJ) would later value BCC at a staggering $4.3 billion, making it one of the fastest “success stories” in the crypto universe—at least on paper. The illusion shattered once US investigators detected signs of a global Ponzi scheme. BCC’s value collapsed by nearly 98 per cent, wiping out an estimated $2.4 billion in savings across the world.

In January 2018, BCC’s Surat-based promoter Satish Kurjibhai Kumbhani—also known online as “Vindee”, “VND” and “vndbcc”—urged his international network of promoters to buy the coin on all cryptocurrency exchanges to artificially inflate its price. But it was too late by then. A Korean promoter warned him that “Koreans are freaking out”, as many of them had invested their life’s savings. Another posted in a BCC chat room: “Some people here are talking about committing suicide. Please, please! Post something on BCC website so people know what’s really going on.”

A promoter in Indonesia told Kumbhani that investors there wanted to approach the police. Chaos erupted after US agencies began taking action against BCC. On January 4, 2018, the Texas State Securities Board issued an “emergency cease and desist order”; five days later, North Carolina followed suit. As scrutiny grew, BCC abruptly shut down its lending programme on January 16. The platform became worthless. “Investors in BitConnect who did not cash out before shutdown lost all, or nearly all, of their investments,” the DoJ said.

The BCC saga exposes the dark underbelly of new-age money laundering. As funds move through the cryptocurrency maze, global investigating agencies, including the Enforcement Directorate in India, have turned their focus towards crypto markets to track illicit fund flows and investor fraud. The ED found that Kumbhani and his associates, without Reserve Bank of India approval, had collected nearly Rs19 crore in cash and an additional Rs 40-50 crore in BitConnect coins from investors, luring them with promises of high returns.

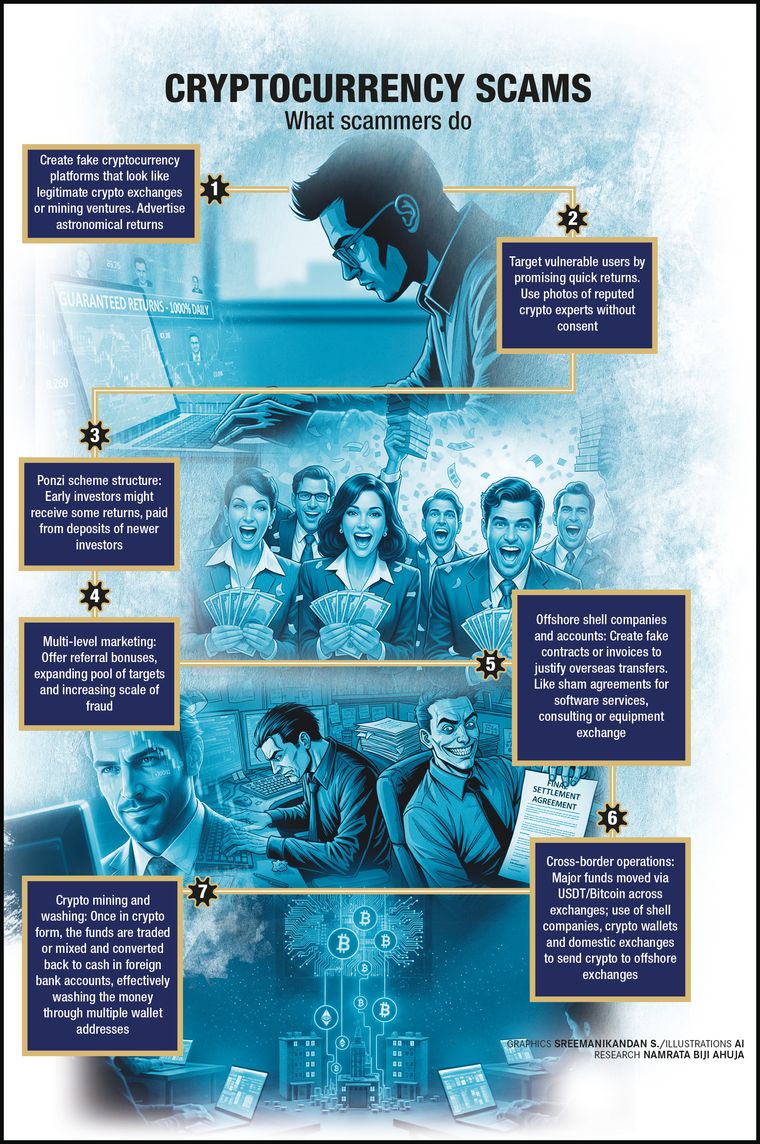

Founded, launched and owned by Kumbhani, BCC allegedly ran its fraud between November 2016 and January 2018. According to the ED’s prosecution complaint, Kumbhani offered what was essentially a sale of securities through BCC’s “lending programme”. Promoters were paid commissions on every new investment they brought in; he convinced investors that BCC used a “volatility software trading bot” capable of generating returns of “up to 40 per cent per month”.

But no trading bot existed. Instead, investor funds were allegedly routed into digital wallets controlled by Kumbhani and his associates. New deposits were used to service withdrawal requests from earlier investors—typical of a Ponzi scheme. As the crackdown began, the ED attached moveable and immovable assets, including cryptocurrencies, worth nearly Rs 2,150 crore as proceeds of crime under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act.

Documents accessed by THE WEEK reveal that at the height of his influence, Kumbhani organised promotional events worldwide. At one such event in August 2017, Kumbhani reportedly told a gathering that if the Indian government discovered the true owner of BCC, enforcement action could follow and investors would lose their money.

In UK registration records, one “Ken Fitzsimmons” was listed as BCC’s corporate officer. Kumbhani later admitted that the name was used to preserve his anonymity. In his defence, he claimed BCC neither violated regulations nor involved taxable assets. But when questioned about the trading bot, he remained evasive, citing privacy as the reason for withholding information from investors, and later, from investigators. Now under the FBI lens and wanted in a money laundering case, Kumbhani remains at large.

“This wasn’t a simple crypto scam,” says Prashant Mali, a Mumbai lawyer and cyber expert. “It was a globally coordinated psychological heist. While the mastermind operated from India, the platforms were in Hong Kong and the UK, investors were in the US, and promoters were scattered worldwide. Everyone had partial jurisdiction; no one had full traction.”

In such cases, Mali says, enforcement becomes reactive, not preventive. “BitConnect exploited the grey zone ruthlessly. What is urgently needed is not just filling gaps in crypto laws, but setting up a transnational joint cyber task force to investigate latest digital frauds,” he says.

In October, the ED provisionally attached cryptocurrencies worth nearly Rs 2,385 crore—the largest such seizure to date—in its ongoing investigation into the unauthorised forex trading platform OctaFX.

The investigation, based on a first information report filed in Pune, found that OctaFX ran a Ponzi-style operation masterminded by Pavel Prozorov, arrested in Spain. Between July 2022 and April 2023, Indian investors were allegedly duped of Rs 1,875 crore, generating profits of around Rs800 crore. Total profits from India allegedly exceeded Rs 5,000 crore, much of it transferred overseas.

OctaFX allegedly presented itself as an online currency trading platform without RBI permission. Initial investors received small profits to build trust—a typical Ponzi tactic. The network operated through entities in British Virgin Islands, Spain, Cyprus, Georgia, Estonia, Dubai and Singapore.

OctaFX, however, dismissed all the allegations. “We strongly refute any allegations of money laundering, promises of quick riches and high returns, and trading manipulations. The global broker Octa is operating in accordance with the laws and regulations of the jurisdictions in which it is registered and conducts business,” the firm said in a statement. “As a global broker, Octa is neither involved in nor has any information about Pavel Prozorov's affairs.”

Last year, Interpol’s strategic analysis ranked money laundering as the second highest crime threat, just behind drug trafficking. Complexity has increased, as criminals are leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning to refine laundering techniques.

In India, digital financial frauds, increasingly facilitated by crypto platforms, recorded a 50 per cent rise this year. Indians lost Rs 22,845 crore in 2024 against Rs7,465 crore in 2023. As many as 36.4 lakh cases were registered in 2024 against 24.4 lakh cases in 2023. Much of this money enters international hawala circuits, intensifying the need for cross-border collaboration.

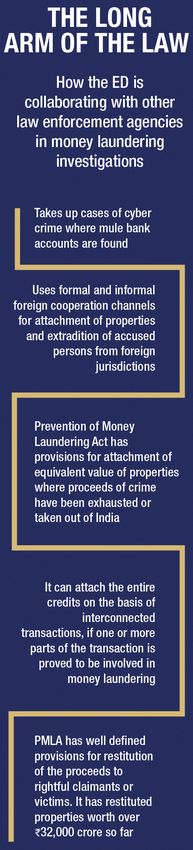

The ED’s focus has shifted from merely catching fraudsters to restoring assets to victims. As on March 31, assets worth Rs 1,54,594 crore was under provisional attachment. In 2024-25 alone, restitution of Rs15,261 crore was done in 30 cases. Overall, assets worth more than Rs 32,000 crore have been returned to rightful claimants.

In August 2025, ED officers were poring over bank records at a registrar’s office in West Delhi’s Janakpuri in connection with a case involving Chirag Tomar, convicted by a US court for spoofing the website of Coinbase (one of the largest virtual currency exchanges) and defrauding more than 700 victims of $20 million. Arrested by the FBI in December 2023, Tomar, 30, allegedly created a fake URL that mimicked Coinbase’s “pro” platform.

Investigators said Tomar was assisted by a team of crypto convertors, mostly family members and friends, who converted the loot into cryptocurrency and moved it to online wallets. Bank records showed Rs 293.85 crore were credited to accounts linked to his family members and associates. Much of it was spent on luxury watches, cars, properties and foreign travel. The ED has arrested three associates and attached Rs64.15 crore so far. Last August, a district court in the US sentenced Tomar to five years in prison.

“Traditional hawala relied on trust-based, off-record value transfer, but crypto replicates this through fast, borderless transactions,” says Brijesh Singh, cyber expert and additional director general of Maharashtra Police. “With newer tools like mixers, cross-chain bridges, decentralised exchanges and privacy coins at their disposal, scammers and organised networks are moving globally without direct identity linkage, making tracing difficult for law enforcement.”

Beyond scams, digital frauds also fuel the online black market—particularly narcotics trade on the dark web. In 2022, the US DoJ wrote to the ED seeking legal assistance to prosecute brothers Parvinder and Banmeet Singh, who ran an international drug racket using marketing sites on the dark web such as Silkroad and Dream Market, and a network of suppliers and distributors on ground. The brothers were paid in cryptocurrency, which was later laundered through online wallets. The Singh brothers had set up a pharmaceutical manufacturing unit in Uttarakhand called Denver Healthcare, and they started selling controlled substances online in 2012. They targeted customers in the UK who paid them in Bitcoins. Between 2012 and 2017, they earned around 8,000 Bitcoins from the illegal sale of drugs.

Vikram Subburaj, an IIM Calcutta alumnus who founded the cryptocurrency exchange Giottus in 2017, says 80 per cent of users on crypto platforms are in the 20-35 age group. Youngsters dabble in digital currencies because it is easier for them to grasp digital assets than for those who need to unlearn and relearn. “My platform has 1.3 million customers and a good number would be in the age group 20-35,” Subburaj says.

Shreyan Gupta, a blockchain expert, says the crypto space is “fast-moving, and full of opportunity—just like any other scam”. “The tech-savvy scamsters understand how to exploit the digital ecosystem,” he says.

The silver lining, say investigators, is tools like artificial intelligence and machine learning for predictive risk analysis. “The use of advanced technologies would enable us to move from reactive investigations to proactive disruption of illicit networks,” says Rahul Navin, ED director. “Our aim is to combine human expertise with technological power to ensure that illicit trade and money laundering become increasingly difficult, expensive and risky for criminals.”

Tracing illicit financial flows could take five years or more, but with integration of advanced tools and databases, investigations are gaining speed. The ED is training sleuths in using forensic tools such as Inter-Operable Criminal Justice System (ICJS) to identify layering and integration patterns across hundreds of bank accounts within minutes.

In 2024, the ED unearthed an international hawala racket involving Rs 4,000 crore. The alleged kingpin was 38-year-old Manideep Mago, 38, a resident of Delhi’s Janakpuri. The probe started after the ED received information that Mago’s Birfa IT solutions Pvt Ltd had sold large volumes of crypto assets and encashed Rs 1,858 crore through an Indian crypto exchange.

Mago’s company allegedly sourced crypto assets from abroad, sold them in India, and converted the proceeds into rupees. Fake invoices were generated and shell companies were created in the name of employees. Mago and an associate in Canada allegedly controlled entities abroad to divert funds to the tune of Rs 4,800 crore. Mago is currently in jail, and the ED has provisionally attached assets worth Rs 47.6 crore.

“From a criminal’s point of view, the market for traditional scams is far bigger,” points out Rajagopal Menon, vice president of the cryptocurrency exchange WazirX. “The fact that India has near-universal bank account ownership and hundreds of millions of people making payments through UPI, is giving scammers a much larger and easier target pool.”

Menon, however, believes crypto frauds are easier to crack than traditional hawala. “Crypto is still not the best tool for laundering money,” he says. “First, KYC [norms] are stringent. Second, you cannot move large sums into crypto without tripping compliance alarms. Three, every transaction is traceable on the blockchain.”

But transnational networks operate through a web of interstate handlers, often causing investigators to lose the trail. An FIR registered in Haryana’s Panipat revealed how Kerala-based “mule” bank accounts were being used by scamsters to run online betting platforms and Chinese loan app scams, with crypto facilitating fund transfers.

In 2021-22, Prema Bhatt (name changed), a resident of Panipat, received a WhatsApp link. After clicking it, Rs 2,500 was credited to her account. But her phone was hacked and data stolen. She later received Rs 1.7 lakh in multiple tranches through different apps. The scammers threatened to circulate morphed photos unless she repaid double the loan amount. They extorted Rs 4 lakh, and even after an FIR was registered in 2022, the harassment continued. The probe revealed that a bank account linked to the scam was opened in Canara Bank’s Ernakulam branch in Kerala, while the loan apps were operated from China. After this case, nearly a dozen FIRs were registered in Kerala. Investigators found that mule accounts in the state were used for instant loan apps, online gambling, betting, gaming, and investment scams. About Rs 444.85 crore routed through these Kerala-based accounts was invested in digital assets on an Indian crypto platform, with part of the money later remitted to Singapore through shell entities. The ED has frozen Rs 123.58 crore in such bank accounts, attached properties worth Rs 9.94 crore, and arrested six people.

The global money laundering watchdog, Financial Action Task Force, says it is important for financial intelligence units of countries to access widest possible range of financial, administrative and law enforcement information. But the reality is that there is little collaboration between police forces of different countries. India has a “mutual legal assistance treaty” with only a limited number of countries, giving criminals a wide leeway to operate in countries with which there is no treaty.

The trajectory of Amit Bhardwaj, a software engineer who became one of India’s biggest crypto fraudsters, illustrates how grey zones attract youngsters Raised in Pune, he joined a leading software company in 2005, and later founded Nextgen Facility Management Services Pvt Ltd, a software services firm. Health setbacks followed—kidney disease forced him to work from home.

While on dialysis, Bhardwaj immersed himself in blockchain and Bitcoin mining. In 2014, he launched a cloud-mining platform called gainbitcoin.com that claimed to purchase computational power from global mining giants using Bitcoin and sell them to retail investors as cloud-mining contracts. For 18 months, customers received fortnightly payouts, pegged to real time mining performances. Between April 2015 and November 2017, the portal reportedly sold 70,000 to 80,000 Bitcoins at an average price of $500-800 per coin. A referral system accelerated growth, with the portal retaining margins of nearly 40 per cent.

But by late 2017, pressure mounted as investors—from engineering students and BPO workers to small-town crypto clubs— began losing their savings. The portal was shut down in November 2017. Bhardwaj was arrested the following year under the anti-money laundering law, after the Pune Police’s cyber-crime cell registered an FIR. The total proceeds of the crime were later pegged by the ED at Rs 6,600 crore.

Bhardwaj died in 2023, but investigators say his model has since been replicated by dozens of crypto-mining rackets. Under existing laws, authorities can attach assets of equivalent value even if proceeds of crime are exhausted, moved abroad, or withdrawn in cash. The ED’s extraterritorial reach and emphasis on prompt action is keeping alive the possibility of restitution for victims of new-age hawala scams.