WHEN INDIA HELD its first general election in 1951–52, only those aged 21 and above could vote. Still, over 17 crore citizens lined up, a staggering number in a nation where the majority were under 35, hopeful and untested in democracy. Four decades later, the voting age was lowered to 18, recognising the rising political consciousness of young Indians. But the right to contest remained out of reach. One could vote for leaders at 18, but not become one until 25.

That gap has only grown sharper. India is among the youngest countries in the world, with a median age of 28 and nearly 65 per cent of its people under 35. In 2019, 1.5 crore first-time voters aged 18–19 entered the voter rolls. By 2024, that number had climbed to 1.85 crore. Parties now chase their votes with promises of jobs, digital futures and climate action, yet deny them a seat at the table where those very decisions are made.

The Panchayati Raj system already allows individuals as young as 21 to contest elections. Thousands of young sarpanchs and panchayat members across India are governing villages, handling finances and shaping rural development.

Telangana Chief Minister Revanth Reddy recently suggested lowering the qualifying age for MLAs to 21. His statement has triggered a larger debate. Should India revisit the constitutional age bar that prevents millions of politically conscious young Indians from entering legislative politics until they turn 25? The issue goes beyond legal technicalities. It cuts to the heart of what kind of democracy India aspires to be: one that merely gives its youth a vote, or one that also gives them a voice.

The contradiction becomes starker when viewed alongside the fact that many influential youth leaders like Hardik Patel, Kanhaiya Kumar and Chandrashekhar Azad had significant following before they were eligible to enter legislative politics.

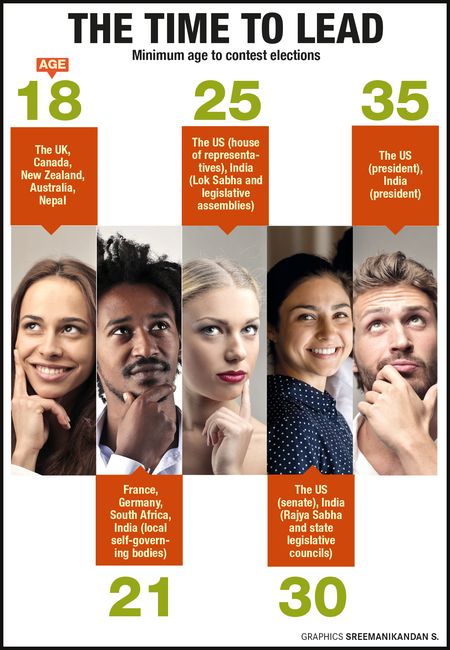

India’s conservatism stands out in global comparison. Many democracies, both developed and developing, trust their youth with candidacy at a much younger age. With senior politicians dominating both houses of Parliament, policy often reflects the priorities of older demographics. Lowering the age could help bridge this gap and create intergenerational dialogue within legislatures.

At present, many aspirants spend their early twenties in political limbo, active in party youth wings but unable to contest. Lowering the age would allow them to test their leadership skills earlier, creating a pipeline of talent not entirely dependent on political dynasties. The experience of local governance already shows that 21-year-olds are capable of handling responsibilities. Extending this to assemblies or Parliament is a logical next step.

Yet there are counter-arguments. Governance requires not only energy but also judgment, experience and the ability to handle complex negotiations. At 21, many individuals may lack these qualities. Younger legislators might also be more vulnerable to being controlled by senior politicians, reducing them to figureheads rather than independent voices.

Vijay Kumar Hansdak, a three-time MP from the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, entered Parliament at around 30. He argues that keeping the age bar at 25 is wise. “I believe that at 18, people are still studying and may not have a full understanding of right and wrong. Some lessons come from school and college, but many are learned only when they step into the real world. This adds to one’s thought process,” he says. “That is why keeping the age limit at 25 to contest elections is, in my view, a good decision. I am a three-time MP, and even today, every time I enter Parliament, I continue to learn something new.”

The demand to revisit the age bar is not new. In August 2023, a parliamentary standing committee headed by BJP leader Sushil Kumar Modi recommended reducing the minimum age for contesting assembly and Lok Sabha elections from 25 to 18, placing India in line with countries such as Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand, where voting and candidacy rights are inseparable.

The committee argued that giving young Indians the right to contest at 18 would enrich policymaking with broader youth perspectives and tap into the energy of a demographic that already forms the backbone of electoral politics. However, the Election Commission of India opposed the proposal, terming it unrealistic. It argued that while 18-year-olds may be politically conscious, expecting them to shoulder the responsibility of legislative work, lawmaking and constituency management was premature. In its view, lowering the contesting age to 18 risked sending underprepared candidates into assemblies and Parliament, potentially diluting the quality of governance.

This clash between the Parliamentary committee’s progressive recommendation and the EC’s cautious stance underscores the larger tug-of-war in Indian democracy: whether to treat youth as active lawmakers or confine them to the role of enthusiastic voters and street agitators.

“The Parliamentary committee was right to highlight global precedents,” says senior advocate Sanjay Hegde. “But the Election Commission’s hesitation shows deep institutional conservatism. In truth, both sides miss the larger point: democracy is about choice. If people don’t trust an 18-year-old candidate, they won’t elect her. Why deny her the right to run? By imposing an age bar, we are not protecting democracy, we are restricting it. The electoral process has its own in-built filter. Candidates must win the confidence of the people. If an 18-year-old can inspire that trust, the Constitution should not stand in the way.”

Lowering the age for MPs or MLAs inevitably raises awkward questions. Can a 21-year-old legislator, who may not be legally permitted to have a drink in many states, make laws prescribing that very drinking age? The contradiction highlights how arbitrarily maturity is defined in law.

India’s legal framework is full of such inconsistencies. The age of marriage is 18 for women and 21 for men. Constitutional offices impose higher thresholds: 25 for Lok Sabha and state assemblies, 30 for Rajya Sabha and state legislative councils and 35 for president.

The juvenile justice debate after the 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape exposed the deep societal unease about where to draw these lines. Outrage over one of the accused being tried as a minor forced Parliament to amend the law, permitting juveniles between 16 and 18 to be tried as adults in heinous offences. If 16-year-olds can be held criminally responsible for grave crimes, is it really unthinkable for 21-year-olds to shoulder legislative responsibility?

Lowering the contesting age would also ripple into India’s vibrant world of campus politics. At present, students’ unions act as laboratories for democratic training, but their role is limited to agitation and organisation. Most mainstream parties maintain youth and student wings that channel politically active students into the system. Yet their trajectory is often frustrating. They spend their early twenties campaigning, mobilising and building networks, but cannot test themselves in elections until 25.

Legal scholars are divided. Some argue that the age thresholds in the Constitution reflect a paternalistic approach, where the state assumes that young people are not capable of responsible governance. “If the state trusts an 18-year-old to elect the government, it should also trust her to be elected,” constitutional expert Faizan Mustafa has argued in public lectures.

For now, Revanth Reddy’s suggestion may remain just that. Changing the age requirement for contesting elections would require a constitutional amendment, needing a two-thirds majority in both houses of Parliament followed by ratification by at least half the states. Given that most current legislators fall well above the age bracket in question, there is little incentive for them to champion such a reform. Interestingly, the Law Commission of India has not formally recommended lowering the contesting age in recent reports, though it has repeatedly highlighted the need to deepen political participation of youth through other reforms, including political party democratisation and electoral financing.

If the bar were lowered to 21 years, ambitious student leaders could leapfrog directly from campus to the legislature. That shift might fundamentally alter the nature of student politics. Would universities then become quasi-electoral training grounds, blurring the line between academic spaces and political battlegrounds? Or would mainstream parties lose interest in nurturing separate youth wings, knowing that talented leaders could bypass them and head straight to the ballot?

Critics caution that while campus politics teaches mobilisation and rhetoric, governance requires a different skill set—budgeting, lawmaking and negotiation. But the counter-argument is compelling: unless young people are tested in real legislative environments, how will they ever build that experience?

The push for younger lawmakers has also run into a counter-narrative: should there be a retirement age in politics? The idea of capping political careers at 75 has sparked debate, sometimes stark, sometimes introspective. RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat ignited discussion when he said that political leaders should retire at 75, fuelling speculation about succession plans, especially as Prime Minister Narendra Modi approaches that milestone. Bhagwat later clarified that he never said anyone must retire at 75, putting the lid on the idea of a formalised age cap for now.

Such conversations underscore a broader shift in democracies that seek fresh blood along with the wisdom of experience. A middle path could be to first allow state assemblies to experiment with a 21-year threshold, and based on that experience, extend it to Parliament.