FOR 40-YEAR-OLD Savita Devi of Amor, Bihar, the right to vote feels as though it is slipping through her fingers. Twice she walked to the booth-level officer’s desk, clutching every document she could find—Aadhaar, ration card, electricity bills—and twice she returned home as if invisible. When the Election Commission’s draft voter list was published, her name was still missing.

Savita Devi is not alone. Across Bihar are others fighting an almost absurd battle for their official existence. Two such people even stood before the Supreme Court on August 12—alive and breathing, yet officially dead according to the draft voter list. Psephologist Yogendra Yadav, appearing in person before the court, called this “just the tip of the iceberg”. What troubled him most, he said, was an unprecedented trend: more women voters have been struck off than men. “Why are women disappearing from the rolls in greater numbers?” he asked the court.

In Amor block, with about two lakh voters, a local party leader said around 40,000 voters were deleted from the list. “There are also those missing in the list under migrated category who have married [mostly women] in another block, and their name is not in any list,” said the leader.

The numbers from Amor are a part a much larger churn. Nationwide, the Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has removed about 65 lakh names from draft rolls—an annual clean-up aimed at deleting duplicates, the deceased, and those who have shifted residence. But the process has made voters like Savita feel that they have been denied their most basic democratic right.

Rashtriya Janata Dal MP Sudhakar Singh was blunt. “The EC’s claim that they are issuing notices to people whose names have been struck is all sham,” he told THE WEEK. “Not a single voter I’ve met has received one. We are not going to sit down—we will file appeals, knock on every door if we have to, to make sure every voter gets their right to vote.”

According to Singh’s close aide, 17 voters from a single booth in the Ramgarh assembly seat were listed as alive on January 1, 2025. After the SIR, though, all 17 are shown as dead—even though they are very much alive. This, he said, is from just one of the 342 booths in the constituency.

In Amor, more than 80,000 names out of a total of around three lakh voters have been removed. “We can help remove Bangladeshis; but citizens should be given their rights,” said Azam Rabbani, representative of MLA Akhtarul Iman.

SIR is intended to ensure rolls are accurate before major elections. This year’s exercise, however, has been unusually aggressive. The EC insists that every deletion follows verification by booth-level officers (BLOs), public notice, and an opportunity to file objections. But the ground reality suggests gaps. In many areas, the notice never reaches the voter in time, or the BLO visit happens when labourers are away on work.

Since 1950, India has undertaken just 13 intensive revisions of its electoral rolls. But never before has the EC appended the word “special” to such a nationwide exercise. The word has transformed what is typically a quiet, bureaucratic update into a political flashpoint, with states like Bihar, West Bengal, Manipur and Delhi witnessing unrest.

“If it is carried out without transparency and due process, it risks becoming a tool of exclusion,” former Supreme Court judge Madan Lokur told THE WEEK. “Disenfranchising voters in the name of administrative efficiency undermines constitutional values.”

According to the EC, the exercise is part of routine maintenance. “It is neither novel nor sinister. Such revisions happen regularly,” said an EC official. “This is part of our institutional calendar.”

The SIR in Bihar marks a sharp departure from past roll revisions. Traditionally, the EC conducted either summary revisions—annual, limited update—or full intensive revisions, involving door-to-door verification, last seen in Bihar in 2003. This time, the EC has adopted a hybrid, truncated version termed special, deviating from both established formats. Unlike past revisions, which included fresh enumeration and home visits by BLOs, the ongoing SIR relies on pre-filled forms requiring voters—especially those enrolled post-2003—to submit proof of citizenship. This shift reverses the burden of proof from the state to the individual, disproportionately affecting marginalised groups.

The revision, therefore, has the opposition viewing it as a tool for targeted disenfranchisement. The controversy has national implications. States where the BJP is not in power have concerns of arbitrary deletions, raising questions about whether the EC is exercising its mandate under pressure.

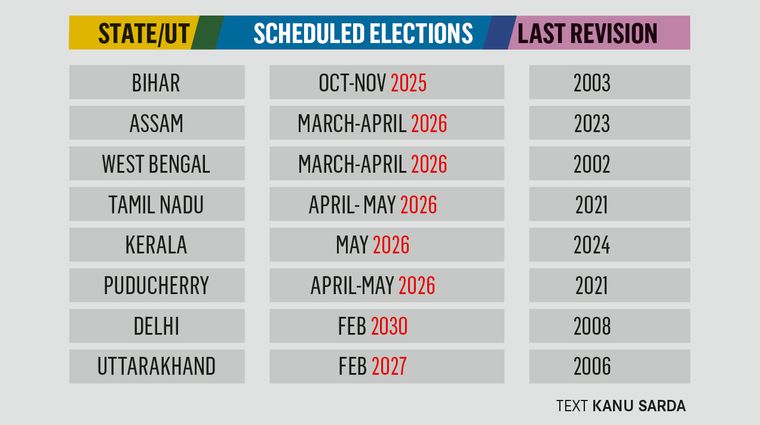

Former chief election commissioner O.P. Rawat said the timing of SIR was crucial. “An SIR is ideally conducted at least a year before assembly polls,” he said. “This ensures that there is ample time for notice, response, corrections and transparent scrutiny. Conducting such an exercise too close to elections risks excluding genuine voters.”

Rawat added that the Special Summary Revision (SSR), a routine annual exercise, is less intensive and can be done closer to elections—typically three to six months prior. “Confusing the two, or fast-tracking a detailed SIR process in the guise of SSR, creates apprehensions,” Rawat said. “Voter disenfranchisement, even if unintended, must be avoided at all cost.”

In West Bengal, SIR has stirred unease among both the ruling Trinamool Congress and civil society groups. The state had witnessed earlier allegations of targeted voter deletions. In the ongoing SIR, there have been reports from constituencies like Cooch Behar, North 24 Parganas and Howrah that suggest abrupt notices served to voters without adequate field verification.

In Manipur, SIR takes on a more fraught dimension, given the ethnic conflict that has displaced tens of thousands of people. Many voters, especially from the Kuki-Zo community, are internally displaced and unable to access their polling areas. Civil society groups argue that if BLOs rely on physical verification alone, these displaced voters risk being struck off the rolls. This could further alienate marginalised groups.

Samajwadi Party MP Javed Ali Khan said the opposition is prepared to pursue the SIR issue through every possible legal and institutional channel. “We will take this matter to its final legal and regulatory consequences,” Khan asserted. “We are very hopeful that the Supreme court will act in a just manner.”

In Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party and the Congress claim that the process may already have started indirectly. “Once they do it, we will involve our people and review the list,” said Rajesh Garg, chairman of the Congress’s booth management committee.

Responded Krishna Sagar Rao, the BJP’s chief spokesperson: “The EC has independently taken up SIR. There are reasons why they are correcting electoral rolls, and they are doing it [through] a scientific process. Opposition parties can very well verify it.”

As SIR proceeds, its real test will not be in how many names are deleted or added, but in how many rightful voters are able to vote without fear or omission. If the EC fails in that, it risks enabling the very disenfranchisement it was meant to prevent.