In a country where the law must speak in many languages and understand countless realities, how representative is the apex court?

The Supreme Court has a sanctioned strength of 34 judges, including the chief justice of India, and wields original (authority to hear a case for the first time), appellate and advisory jurisdiction. However, beneath the court’s lofty mandate of upholding the Constitution and being the final arbiter lies a persistent issue—the lack of adequate regional representation from India’s 25 High Courts on its bench. This gap raises a pertinent question—can the court grasp the complexities of every corner when some regions have no voice?

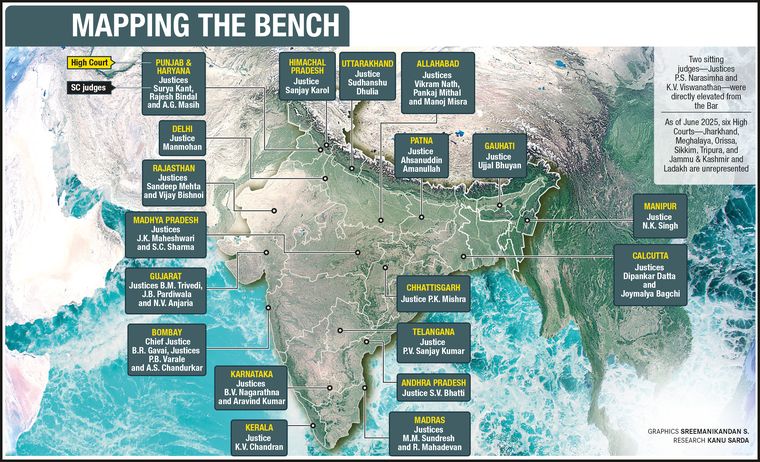

As of June 2025, the High Courts of Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Orissa, Sikkim and Tripura, and the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh have had no judges elevated to the Supreme Court since 2018, raising questions about the collegium’s approach to appointments and whether such practices are fair and diverse.

The High Courts, established under Article 214 of the Constitution, serve as the primary appellate courts for their respective regions, handling a vast array of cases that reflect the unique sociocultural, economic and legal contexts of their jurisdictions. The Supreme Court, drawing its judges primarily from these High Courts, is expected to embody the nation’s diversity to ensure that its rulings resonate with the varied experiences of India’s populace.

Regional representation is not merely a symbolic gesture—it is a functional necessity. Judges from different High Courts bring nuanced perspectives shaped by their regional legal ecosystems. For instance, a judge from the Gauhati High Court, which oversees the complex sociopolitical dynamics of the northeast, may offer insights into tribal laws or insurgency-related cases that differ from those of a judge from the Delhi High Court, which often focuses on constitutional matters. This diversity enriches the Supreme Court’s deliberations, ensuring that its judgments are not only legally sound but also contextually relevant.

Regional representation is evaluated based on a Supreme Court judge’s parent High Court, the court where they first became a High Court judge. A lawyer can also become a Supreme Court judge directly.

In the petitions challenging the abrogation of Article 370, one of the judges on the Constitution bench, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, now retired, hailed from Jammu & Kashmir. His personal and professional familiarity with the region’s demographics, political history and legal peculiarities added a layer of grounded understanding to the bench’s deliberations. This background is critical when the court deals with questions that go into the social and political ethos of a region.

The Supreme Court collegium, led by the chief justice and comprising the four most senior judges, is responsible for recommending judges for elevation to the top court. While the collegium considers multiple factors—seniority, merit, integrity, gender, caste and regional diversity—there is no fixed formula governing how these criteria are balanced. Regional representation, though explicitly acknowledged as a criterion, often takes a backseat to seniority or merit, leading to skewed representation.

The Supreme Court currently operates with 33 judges. This is after the appointment of Justices N.V. Anjaria, Vijay Bishnoi and A.S. Chandurkar. These appointments have bolstered representation from Gujarat, Rajasthan and Bombay, but the six unrepresented High Courts collectively account for a significant portion of India’s judicial workload.

The most represented High Courts include Allahabad, Bombay, Gujarat, and Punjab and Haryana, each contributing three judges to the Supreme Court. The Delhi High Court, which had four judges as recently as September 2023, now has only one representative—Justice Manmohan. Other High Courts, such as Kerala, Madras, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Patna, have just one judge each. This disparity highlights a systemic issue of larger, politically influential High Courts dominating the Supreme Court, while smaller or less prominent ones, particularly from the northeast and newer states, are consistently overlooked.

But, it is not merely seniority at the all-India level that determines elevation, but also the depth, quality and subject matter of the judgments delivered by a High Court judge whose name is under consideration. These written decisions are a reflection of a judge’s legal acumen and judicial temperament and they carry considerable weight in the selection process.

Speaking to THE WEEK, former Supreme Court judge Justice Hrishikesh Roy, who had served as a member of the collegium, shed light on the meticulous process behind recommending names for elevation to the apex court. “When the five collegium members deliberate on a potential elevation, our primary objective is to select the most meritorious and deserving candidate,” he said. “The first and foremost consideration is the overall impression of the judge—this includes feedback and opinion from fellow judges of the same High Court. Following this, we closely examine the quality of the judge’s written judgments, particularly legal mastery and the reasoning for the decision. Focus is to pick the best, even if a representative consideration is to be made.”

Justice Roy elaborated that while an all-India seniority list exists, the key concern is balancing seniority with regional representation—“ensuring that the recommended judge not only is competent in terms of judicial writing, but also hails from a High Court that may be under-represented”. He explained that if a judge from a High Court lacking representation was significantly lower on the seniority list, then seniority took precedence over representation. “Giving preference only to under-represented High Courts, without regard to seniority, would disrupt the seniority framework among judges,” he said.

For example, earlier this year, the collegium led by then chief justice of India Sanjiv Khanna took regional representation into account when recommending Justice Joymalya Bagchi for elevation.

But the issue of regional representation is not new. Data shows that the Delhi and Bombay High Courts have consistently sent the most judges to the Supreme Court, a trend attributed to their large sanctioned strengths and their historical prominence as pre-independence courts. In contrast, smaller High Courts, like Sikkim and Meghalaya, have negligible representation. The northeast has been historically under-represented, with only the Gauhati High Court currently having a single judge, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, on the Supreme Court bench.

The collegium’s resolutions often cite the sanctioned strength of High Courts to justify appointing multiple judges from larger courts like Delhi or Bombay. For instance, in 2023, the collegium noted that the Rajasthan High Court, a large High Court, warranted representation when recommending Justice Sandeep Mehta. Similarly, Justice S.V. Bhatti’s appointment was justified to ensure representation from Andhra Pradesh.

The Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh High Court has had no representation since 2010; Jharkhand and Orissa High Courts, with respective sanctioned strengths of 25 and 33, handle substantial caseloads but remain unrepresented.

Kaul told THE WEEK that regional representation was an important criterion and a legitimate expectation, and stressed that there was urgent need of having High Court chief justices from the respective states.

It was during Kaul’s tenure as a collegium member that judgments of the judge under consideration for elevation was first included in the discussions. “All discussions are based on the inputs received from respective High Courts,” said Kaul. “We as judges are aware that we are not sitting in glass rooms; we are not whimsical.”

In October 2015, the Supreme Court, while delivering its landmark judgment striking down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act and the 99th Amendment, strongly emphasised the importance of regional representation in appointments to the Supreme Court. The court said ensuring regional, social and gender representation in higher judiciary was essential to strengthening public confidence and maintaining the multiplicity of perspectives, legal traditions and sociocultural realities from across the nation. The judgment noted that some regions had been historically under-represented in the apex judiciary, leading to concerns over inclusiveness and fairness.

Addressing the representation gap requires a multifaceted approach. First, the collegium must prioritise judges from unrepresented High Courts, even if it means deviating from strict seniority norms. The appointment of Justice P.K. Mishra from Chhattisgarh in 2023, despite his junior status, demonstrates that such flexibility is possible when regional diversity is deemed critical.

While merit, seniority and regional representation are taken into account, gender diversity has not been consistently prioritised. Consequently, women judges from various High Courts, even those with exceptional records, often find themselves overlooked for elevation.

This imbalance is not only a matter of representation but also of perspective. The inclusion of more women judges enriches the judicial process by bringing in diverse life experiences, empathetic viewpoints and nuanced interpretations of gender-sensitive issues.

Their presence on the bench sends a powerful message to aspiring women in law that the judiciary is a space where they belong and can thrive. At present, the Supreme Court has just one women judge—Justice B.V. Nagarathna, after the recent retirement of Justice Bela M. Trivedi (resulting in the one unfilled seat on the bench).

The other retirement this year is that of Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia, the only sitting judge from the Uttarakhand High Court. Justice Ahsanuddin Amanullah remains the only Muslim judge and Justice A.G. Masih the only Christian. Justice R. Mahadevan from Tamil Nadu represents the backward community. After Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai’s retirement, Justice P.B. Varale will be the only dalit judge at the top court, if no other is elevated.

Regional representation, along with gender and minority inclusion, should not be incidental, it must be integral. Judicial merit need not be at odds with diversity. Rather, embracing both is key to delivering justice that is not only fair and reasoned, but also truly representative of India.