On April 21, 2022, former Pakistani army major Adil Raja fled Pakistan, boarding a flight to London via Doha, Qatar. The reason: the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s spy agency with which he had once been closely associated, had turned against him.

“They raided my office. They sent about 16 officers to my business address,” said Raja in a witness statement submitted to a UK court. “On April 19, 2022, they raided my mother’s house, where I was living at the time…. The very next day, they raided my mother’s house again. They had no legal right to carry out these raids. No warrant at all.”

Being in exile in London offered no safety. The ISI tracked Raja down and filed a case against him in a UK court—the next hearing of which is on July 21. Meanwhile, back in Pakistan, his bank accounts were frozen, assets confiscated, and his military pension halted. His only crime: being perceived as close to the ousted and now-incarcerated former prime minister Imran Khan, founder of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).

Now based in the UK, Raja has turned to journalism. He runs a YouTube channel, Twitter account and Facebook page with several lakh followers.

In his court deposition, Raja said: “The ISI operates in the UK. They have an office in the Pakistani embassy…. The two ISI commanding officers operating out of the London embassy are Colonel Asad Rasheed, who works with the active assistance of his staff and the army, and Air Attache Colonel Taimoor Khan…. I have been friends with Khan for about 17 years. We served together in the army.”

Raja considers himself fortunate. Arshad Sharif was not.

Sharif, a prominent investigative journalist and TV personality in Pakistan, fled to Dubai on August 10, 2022, to evade ISI harassment. He was soon forced to flee again to Kenya. On October 23, 2022, he was shot dead in Kajiado, approximately 80km south of Nairobi. Kenyan authorities initially claimed his death was a case of mistaken identity at a police checkpoint, but the autopsy revealed that Sharif had been tortured, and his fingernails pulled out before he was killed.

Under growing public pressure, a report was released by Muhammad Athar Waheed, director of Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), which linked ISI officers to Sharif’s killing. Despite this official indictment, no one has been held accountable.

Sharif was believed to have been in possession of documents implicating political leaders and ISI officials in certain corrupt dealings—files reportedly handed over to him by Muhammad Rizwan, who was FIA chief prosecutor when Imran Khan was prime minister. Rizwan was investigating several high-profile corruption cases against politicians. On May 9, 2022, he died in Lahore of a suspected heart attack. The ISI is reported to have blocked his autopsy, amid widespread speculation that he had been poisoned.

Cases of the ISI’s relentless pursuit of political dissidents, rights activists and journalists—particularly those who act against its organisational interests abroad—are now widespread. A recent Human Rights Watch report categorised it as “transnational repression”, encompassing measures such as extrajudicial killings, abductions, deportations, abuse by consular authorities, threats against family members and digital surveillance and harassment.

These operations are the domain of the ISI’s notorious ‘C’ wing, which is mandated to deal with Pakistan’s internal politics. Said prominent Pakistani journalist Ejaz Haider in a podcast: “An intelligence agency where a wing is dedicated to something like this will naturally develop a culture that isn’t strictly in line with the laws and the constitution.”

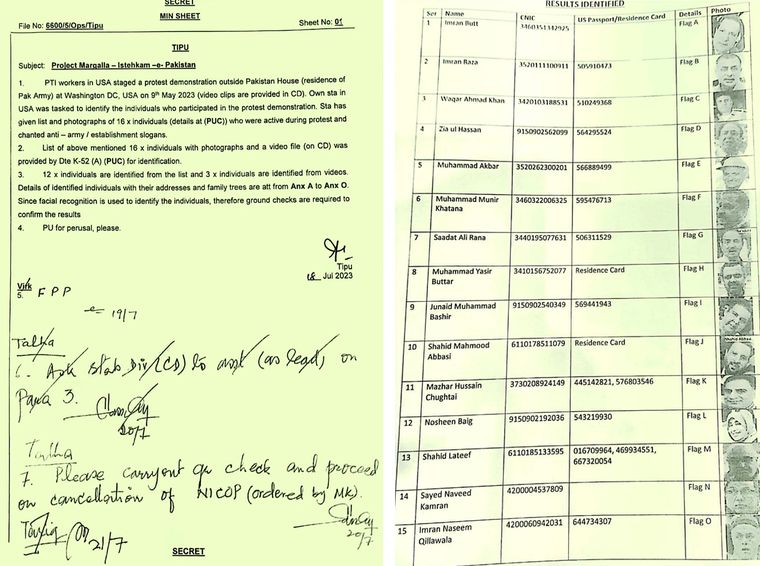

The C wing employs shady tactics. On May 9, 2023, when the PTI organised a protest outside Pakistan House in Washington, DC, ISI headquarters issued a directive tasking agents with identifying individuals who chanted “anti-army” and “anti-establishment” slogans. A classified document named 15 individuals through facial recognition, listed their photographs, passport details, addresses and even family trees.

The operation, code-named Project Margalla-Istehkam-e-Pakistan, included a disquieting file noting: “Please carry out a check and proceed on cancellation of NICOP”. The NICOP, or National Identity Card for Overseas Pakistanis, is an essential identity document for Pakistanis abroad. The file noting put the NICOPs for the 15 individuals at risk. Similarly, Raja’s passport has now been blocked, highlighting how citizenship itself is weaponised.

Founded in 1948 by Australian-born British Army officer Major General Walter Joseph Cawthorn, who chose to serve Pakistan after partition, the ISI was modelled on the British MI6. Trained by the CIA and the SDECE (which was then the French secret service), with an India-centric focus, its early personnel were from the military and the civilian employees of the pre-partition Intelligence Bureau. The ISI’s initial role was reconnaissance and planning military attache postings. It is now organised into several divisions like the ‘Afghan bureau’ and the ‘Kashmir desk’.

The agency has several wings—‘A’ (analysis wing), ‘B’ (strategic and international wing, intelligence acquisition and counter-insurgency operations), ‘C’ (internal security), ‘S’ (intelligence operations), ‘CT’ (counter-terror operations), ‘T’ (signals and technical intelligence), ‘P’ (personnel), ‘I’ (internal wing to spy on officers of the agency itself), and an information management wing that deals with media and cyber operations.

Contrary to popular notion, the ISI’s current strength of about 25,000 employees mainly comprises civilians who are direct recruits. The ratio of civilians to officers on deputation from the Pakistani army, navy and air force—including military officers who are no longer serving but brought in to the ISI on short-term contracts, and from the police and paramilitary services and other specialist units—is about 60:40. The ISI’s top crust comprises only officers from the military, which keeps the agency under military control.

The civilian dominance in the ISI has long unsettled Pakistan’s army generals. Since the era of General Pervez Musharraf, the military has steadily empowered its own intelligence arm—the Military Intelligence (MI)—as a counterweight to the ISI. Under Field Marshal Asim Munir, the current army chief, this shift has become more noticeable.

Munir’s preferred instrument is the MI, led by Major General Wajid Aziz, rather than the ISI under Lieutenant General Asim Malik, even though Malik is considered close to him. “The ISI’s inherent independence is seen as a threat by the army chief, which is why he tasks the MI with monitoring ISI activities,” Raja told THE WEEK. “This often leads to turf wars and friction between the two agencies.”

According to Raja, the MI directorate is located next to the army chief’s secretariat in Rawalpindi. “The army chief exercises complete control over the MI because it falls directly under his command,” Raja said. “Naturally, he would want the MI to have an edge over the ISI, which is constitutionally an independent entity headquartered separately in Islamabad.”

As the army chief does not have direct control, he tries to influence the ISI by posting army officers in commanding positions. “However, the independent nature of the ISI, and the fact that its core strength is built through direct induction, make it almost impossible for the army chief to control the ISI effectively,” said Raja.

The ISI has a significantly higher budget and resources than the MI. Its core strength is based on permanent induction of personnel, whereas the MI relies primarily on military manpower, with a limited mandate that is restricted to military matters. Also, the ISI is trained to operate in civilian and international spheres, which helps it dwarf the MI in scope and influence.

Despite Munir propping up the MI, the ISI maintains its upper hand because it is a civil-military intelligence agency with a global reach. It is also used for domestic counter-terrorism and political manipulation operations. “Therefore, the MI cannot, and will not, prevail over the ISI,” said Raja. “The army chief, consequently, relies on posting loyalists in command positions within the ISI, but they are often temporary appointments.”

In Pakistan’s peculiar military ecosystem, the core strategic strength of the ISI is its permanence, capacity and institutional memory. In theory, the ISI is answerable to the prime minister; in reality, it answers to the army chief, who posts and promotes its officers. While the MI may act as a veto power, it is the ISI that continues to operate with impunity—and appears likely to do so for the foreseeable future.