ONCE A SHARP, eloquent debater from St Joseph’s College, Allahabad—the kind who entered competitions not just to participate but to win—Justice Yashwant Varma carved a name for himself as a figure driven by intellect and ambition. But today, that image is shadowed by controversy. Long known for his courtroom clarity, Varma finds himself at the centre of a storm after unaccounted cash was reportedly found at his Delhi residence while he was away from the city.

Varma belonged to that rare breed: intellectually sharp, clear in thought, firm in his opinions, and quietly efficient. Born on January 6, 1969, in what was then Allahabad (now Prayagraj), he grew up in a family steeped in legal tradition. His father, the late Justice A. N. Varma, served as a judge of the Allahabad High Court from 1978 to 1992. In such an environment, dinner-table conversations often revolved around law, justice and public service—shaping Yashwant’s worldview long before he donned the robe. He later moved to Delhi for higher studies, where he honed both his intellect and confidence. At Hansraj College, University of Delhi, he pursued BCom (Honours), delving deep into numbers, commerce and critical thinking.

But it was not just academics that engaged him. Known among his peers for incisive reasoning and eloquence, he eventually gravitated towards the legal arena, enrolling for LLB at Rewa University, Madhya Pradesh. Returning to Allahabad, he registered as an advocate on August 8, 1992, embarking on a wide-ranging legal practice. He handled matters across constitutional law, labour disputes, corporate litigation, taxation and more. Colleagues recall him as meticulous and sharp—never one to shy away from complexity, always pursuing clarity.

“Back in our days at St Joseph’s College, the big inter-school event was called Confluence—now known as Josephest,” Arindam Gosh, a friend of Justice Varma, told THE WEEK. “He and I would often represent our school. While I explored different competitions, Yashwant was singularly focused on one thing: debating. That was his arena, and he owned it.”

Sujoy Malik, another friend now based in Dubai, remembered Varma as a bright classmate and expressed shock at the current developments. “I will not comment on something that can have multiple angles. All I can say is that he is passing through a terrible time in life. May God be with him, and may he get justice—if he is indeed honest and clean.”

After the discovery of the alleged cash at his residence in March, the Supreme Court swiftly initiated an in-house inquiry and transferred Varma back to the Allahabad High Court, suspending his judicial functions. As per internal guidelines, then chief justice of India Sanjiv Khanna constituted a three-member committee to investigate. The panel found that Varma had committed serious misconduct, prompting the CJI to recommend his resignation. When he refused, the matter was escalated to the president, setting the stage for formal impeachment proceedings.

Under the 1968 Judges (Inquiry) Act, impeachment begins when at least 100 Lok Sabha MPs or 50 Rajya Sabha MPs submit a motion. If admitted, a parliamentary committee—including a Supreme Court judge, the chief justice of a high court and a jurist—is formed to investigate. To remove a judge, the motion must be approved by a two-thirds majority in both houses of Parliament. Only then can the President issue an order removing the judge.

With the monsoon session set to begin on July 21, the government is expected to introduce the motion seeking Varma’s impeachment. But the path forward is far from straightforward. Opposition parties, especially the Congress, argue that the Supreme Court’s internal report alone is not enough, and insist that the statutory process laid out in the Judges (Inquiry) Act must be followed. The Congress has formally requested a copy of the committee’s report before deciding its position.

The situation brings to light the delicate balance between judicial independence and public accountability. No sitting judge in India has ever been removed through impeachment. This case could become a pivotal constitutional moment. Abhishek Manu Singhvi, senior advocate and Rajya Sabha member, has urged Varma to step down, citing the looming impeachment threat and the need to restore trust in judiciary.

For Varma, the pressure is immense. With Parliament’s weight bearing down, resignation may now be his only dignified path. If he resigns, he would still be entitled to pension and post-retirement benefits granted to a High Court judge. But if he is impeached, he stands to lose everything—including pension, benefits and reputation.

The Constitution offers a quiet exit route: under Article 217, a High Court judge can step down by submitting a resignation letter to the president. Judges are also allowed to specify a future date for their resignation, which gives them a window to reconsider before the date takes effect. The only other way a judge can vacate office is through formal removal by Parliament. Supreme Court judge V. Ramaswami and Calcutta High Court judge Soumitra Sen had earlier faced impeachment proceedings, but they resigned.

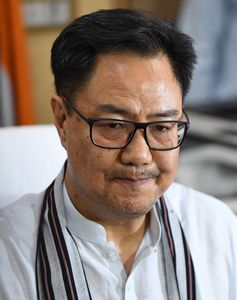

Parliamentary Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju said impeachment discussions can only begin after the parliamentary committee submits its report. The immediate goal, he said, was to move the impeachment motion in Parliament, after which the speaker would take a call on constituting the parliamentary committee. While the earlier committee in this case was not formed by Parliament, he said, it was formed by the chief justice of India and could not be dismissed.

MP and former law minister Kapil Sibal said any move to impeach Justice Yashwant Varma solely on the basis of the Supreme Court’s internal inquiry would be unconstitutional. He also raised a pointed question: why has no action been taken by Rajya Sabha chairman Jagdeep Dhankhar on the long-pending notice to impeach Justice Shekhar Kumar Yadav of the Allahabad High Court? He accused the government of shielding the judge who had reportedly made communal remarks last year. “There can’t be one rule for one judge and another for someone else,” Sibal said.

But experts say a judge cannot be removed without voting in Parliament. “The judgment in C. Ravichandran Iyer v. Justice A.M. Bhattacharjee, delivered on September 5, 1995, established an in-house procedure to address misconduct by judges of constitutional courts, filling a constitutional gap,” former additional solicitor general Biswajit Bhattacharya told THE WEEK. “This procedure was formally adopted by the Supreme Court in 1999 and remains clear. However, the ultimate removal of a judge must still be carried out… through a parliamentary voting process.”

Govind Mathur, former chief justice of the Allahabad High Court, raised a serious concern: while an inquiry under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 is important for determining judicial misconduct, it cannot replace criminal proceedings, especially when the misconduct also amounts to a criminal offence. “In this case, no FIR was registered,” Mathur said. “And without an FIR, the police couldn’t legally seize anything. That’s a fundamental flaw in the process.”

Mathur said judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court cannot be prosecuted without prior CJI consultation—a safeguard to protect the judiciary from frivolous and politically motivated complaints.

Yet legal experts say what followed defied established procedure. The recovery of burnt currency, they argue, could attract multiple offences under various laws—ranging from the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, to the Prevention of Money Laundering Act. These are all cognisable offences, meaning the police had both the power and the duty to act swiftly. The absence of action, say experts, not only damages the credibility of the investigation, but also weakens public trust in judiciary.

At the heart of the Varma controversy lies an issue that is far more consequential and troubling than personal misconduct: the institutional confrontation between judiciary and the executive. The events surrounding the Varma case reveal a system under strain, where questions are being raised whether constitutional safeguards and due process are yielding to political expediency. What began as an internal inquiry has now snowballed into a potential constitutional crisis.

Critics argue that this is part of a larger trend—an increasingly assertive executive trying to restrict judicial independence. From delays in judicial appointments to targeted leaks and media trials, there is a discernible shift in how the government engages with the judiciary. While the pattern of coercion is not new, what makes the Varma issue distinct is the brazen disregard for due process and overt efforts to influence public perception.

“The judiciary is being destroyed in this entire controversy around Justice Varma,” a former Supreme Court judge said. “We are playing into the hands of the government.”

He pointed to the growing perception that executive overreach is threatening judicial independence. The larger worry is that it creates a climate where judges who question executive action increasingly find themselves under scrutiny. If sitting judges begin to see impeachment as a political tool rather than a last-resort accountability mechanism, it could lead to self-censorship, risk aversion, and reluctance to rule against the government in sensitive matters. That would strike at the core of the judiciary’s role as a bulwark against executive excess.

“Justice Varma reportedly hasn’t been given access to the full report, raising serious concerns about due process, fairness and transparency,” said Supreme Court advocate Abhinav Singh. “Using a confidential process, never intended for public or parliamentary scrutiny as the basis for constitutional punishment, sets a dangerous precedent. If the government is seen to have the ability to selectively target judges it finds inconvenient, judicial independence will suffer a chilling effect.”

Another concern is to ensure that the legitimacy of judicial discipline lies not just in outcomes, but in the integrity of procedure. Fast-tracking impeachment without following the statutory framework undermines both.

The need of the hour is clearly institutional sobriety, not political theatre to bring justice. For the judiciary, it is a test of resilience; for the government, a test of restraint. Above all, it is a test of whether constitutional morality can withstand the pressure of majoritarian impulses.