The Lok Sabha elections of 2004 witnessed a big technological leap. The traditional ballot box was completely replaced by the sleek Electronic Voting Machine (EVM). Polling stations across all 543 constituencies resounded with the loud beeping sound made by the EVM every time a voter cast his or her vote. In a first, the counting of the votes was completed in less than a day, which inspired a sense of amazement because the counting of ballot papers would take two to three days.

This important milestone in the country’s electoral history was recorded 20 years ago. Since then, three more Lok Sabha elections and 132 state assembly polls have been held using the EVM. The coming parliamentary elections will be the fifth since 2004 to have universal use of the EVM. It has been an eventful journey for the voting machine, hailed as a uniquely Indian innovation that has transformed the way elections are conducted in the country, even as political parties and other stakeholders have questioned its reliability at regular intervals.

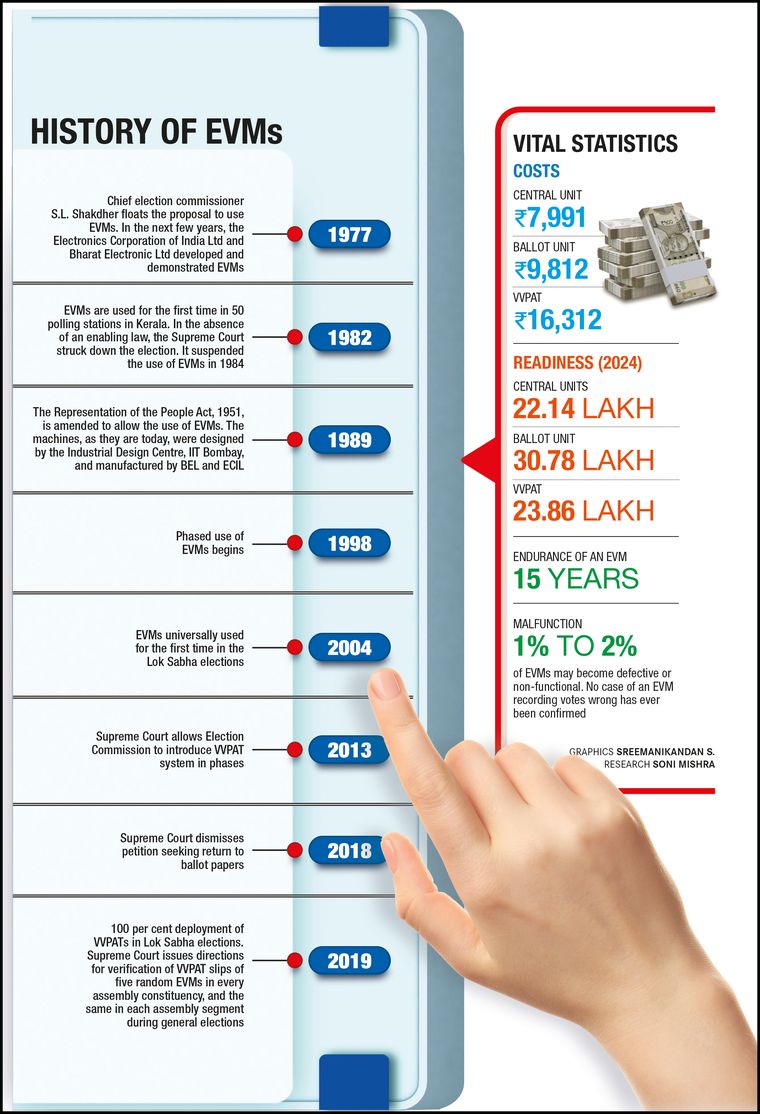

The journey of the voting machine had begun much before 2004 though. In 1977, chief election commissioner S.L. Shakdhar had proposed the idea of developing a voting machine. The Electronics Corporation of India Ltd, Hyderabad, and the Bharat Electronics Limited, Bengaluru, developed prototypes for the EVM.

The voting machine made its debut in some polling stations in Kerala’s Paravur assembly constituency during the byelection in 1982. It was not a dream debut though―the use of EVM was challenged legally, and the Supreme Court ruled that it could not be used in elections since an enabling provision was not present in the law. The Rajiv Gandhi government amended the Representation of People Act in March 1989 to provide for a legal backing to the EVM. And, Section 61A was inserted into the law.

However, from the very start, the EVM has been viewed with mistrust, and claims have been made by political parties and other stakeholders that it could be hacked or tampered with or votes could be stuffed into it. The law was amended to provide for the use of EVM and the plan was to use the machine in the Lok Sabha elections in 1989, but that could not happen in the face of stiff political resistance.

V.P. Singh, the main opponent of the Rajiv Gandhi government, had claimed that the machine was programmed in such a manner that all votes would go to one party only. Chief election commissioner R.V.S. Peri Sastri wrote to Singh, asking why he did not trust him when he had worked with Singh earlier. Singh is learnt to have said that it was a political issue.

Building political consensus took time and effort. In 1990, the Union government set up an Electoral Reforms Committee under Dinesh Goswami, which had representatives from various political parties. The committee was of the view that the EVM must be examined by a team of technical experts. The EVM subsequently got the go-ahead from the expert committee.

Ultimately, it was in 1998 that a broad consensus could be reached on using the EVM, and it made a comeback in the assembly elections held that year in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Delhi, though in a limited manner. They were re-introduced in a graded manner, before the first universal use in the Lok Sabha elections of 2004.

The EVMs have since then not changed much in design, but have undergone technological upgradation. The EVM that was in use before 2006 is known as ‘M1 EVM’ and those that were manufactured between 2006 and 2010 are known as ‘M2 EVM’. The EVM that is in use presently is the ‘M3 EVM’, manufactured since 2013. The M3 EVM also comprises a Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machine, in which a paper slip is generated as a physical evidence of the vote cast. The voter can view the paper slip through a transparent panel on the machine before it falls into the bin within.

There has been no end to political parties questioning the EVM though, and all of them, at different times, have raised doubts about it. BJP’s L.K. Advani had raised doubts about the EVM after the Lok Sabha elections of 2009, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance had won a second time. Demands have also been made that the ballot box system be brought back.

“The ballot box system was marred by various malpractices such as rigging and booth capturing,” said former chief election commissioner S.Y. Quraishi. “There was also the problem of a large number of invalid votes. The huge volume of paper used meant massive damage to the environment.” He also said that if the EVMs could be hacked, the government under which it was first introduced would not have lost any election at all after that.

However, after the assembly elections in December 2023, where the Congress got a drubbing in the Hindi heartland states, veteran leader Digvijaya Singh took it upon himself to prove that the EVM could be manipulated. He claimed that the results in Madhya Pradesh, where his party lost, would have been a lot different if the machines had not been tampered with. He sought to demonstrate using a dummy EVM how the machine could allegedly be manipulated. “Many questions have been raised about the EVM, which have not been convincingly answered by the Election Commission,” he had said. “We still have time to go back to the ballot paper. Ballot papers and boxes can be readied at the district level. It can be done at 50 per cent less cost compared with the EVM.”

On the cusp of another Lok Sabha election, the EVM is yet again at the centre of an intense debate, with opposition parties raising doubts about the machine. At the rally of the INDIA alliance in Mumbai held on March 17 after the completion of the Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra, former Congress president Rahul Gandhi said, “Modi ki jaan EVM mein hai”, implying that Modi and his party are winning because of the EVM.

The INDIA alliance has demanded 100 per cent VVPAT verification. It has, however, been stressed by the Election Commission and former chief election commissioners that there has so far not been a single instance of a VVPAT mismatch.

“If you do 100 per cent VVPAT counting, there is one big risk,” said former chief election commissioner O.P. Rawat. “It can provide people with a chance to sabotage the EVM. The VVPAT slip is very small, just about two-and-a-half inch by two-and-a-half inch. If some miscreants succeed in taking just two or three slips and, say, just eat them, they will get the first case where the VVPAT slip count does not match the electronic count. Just one mismatch, and it will explode into a huge controversy. The commission should continue its outreach to the people because they are the countervailing force against all the political talk.”

While recently addressing the press conference held to declare the schedule of the Lok Sabha election, Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar insisted that the EVMs are 100 per cent safe and foolproof. “A large number of improvements have been made over the years,” he said, “and the political parties and candidates are present at every stage of the EVM movement, right from the first level check to randomisation to the journey to the polling booth and then to the storage centre and finally the counting centre.”

The commission has also highlighted the numerous occasions on which petitions have been filed in the courts raising questions about the reliability of the EVM, but the courts have not entertained any of those doubts.

“The EVM is pure and dependable,” said former chief election commissioner V.S. Sampath. “So far, several petitions have been filed in the courts against the use of EVMs. There has been a series of litigations questioning the reliability of the EVMs. But none have been able to give any proof that the EVM can be manipulated or it can be tampered with in any way. Mere suspicions exist, but there is no proof or solid basis to doubt the reliability of the EVM.”