Everyone wants to know what will happen next in Ukraine, but no one has an answer. The Russian leadership has been vague about the operation, and it remains unclear what its territorial and time-related boundaries are.

As Russian President Vladimir Putin said on February 24, on the first day of hostilities in Ukraine: “The goal of the operation is to protect people who have been subjected to abuse and genocide by the Kyiv regime for eight years, and for this we will strive to demilitarise and denazify Ukraine, as well as bring to justice those who committed [crimes] against civilians, including the citizens of the Russian Federation.” Since then, the wording has not changed.

Presumably, Moscow wants the military to take control of Ukraine from the region of the Donetsk and Luhansk republics to the Dnieper. But, currently, the offensive is underway in western Dnieper. Perhaps these strikes are only to significantly increase the damage to the Ukrainian army and nothing more. But these are just guesses.

Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov said on March 7 that Russia was ready to stop the military operation at any time, provided Ukraine recognises the independence of the Crimean peninsula and the Donetsk and Luhansk republics, and also amends the constitution, refusing to join any bloc (meaning primarily NATO).

Currently, most people are expecting negotiations with Ukraine and the cessation of hostilities. “Russia hoped to sign at least one protocol at the talks with Ukraine, but it failed to sign anything. Russia’s talks with Ukraine will continue in the future.” This is all that the head of the Russian delegation Vladimir Medinsky, the former minister of culture and now assistant to the president, could say at the end of the third round of talks.

Ukraine now feels the support of the whole world behind it and hopes that, faced with full sanctions, Moscow will be more amenable. It is difficult to say how true such a calculation is. Russia cannot now suddenly withdraw troops from Ukraine, having launched a special operation and quarrelled with almost the whole world.

Putin needs to save face and get the opportunity to show himself as a winner, at least in the eyes of Russians. But Kyiv does not want to give him such a chance, so the only hope is pinned on intermediaries from other countries, such as Turkey.

It is almost impossible to understand what is happening in the areas where the fighting is taking place. Each side talks about their victories and the colossal losses of the enemy. But, judging by the leaks from military circles, confusion reigns in the combat area as the start of the special operation was announced unexpectedly and no detailed plans were developed.

Such uncertainty gives rise to a variety of theories. Those who support the special operation hope that Russian troops will take control of at least the eastern and central parts of Ukraine. And the most aggressive openly write on social media that it would be a good idea to enter Moldova, a small country between Ukraine and Romania. Moldova, until 1991, was one of the 15 republics of the USSR.

Opponents of the special operation believe that it will lead to the isolation of Russia from the world, the “Iron Curtain”, the collapse of the Russian economy, a protracted positional war in Ukraine with an unpredictable outcome, and, in future, the possible use of nuclear weapons.

According to public opinion polls conducted between February 25 and 27 by the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM), cooperating with the Russian presidential administration, about 70 per cent of Russians support Moscow’s recognition of the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk republics. Also, 71 per cent of the Russian population supports Putin’s actions. About 8 per cent do not approve of the recognition of the republics, and about 18 per cent do not trust Putin.

It follows from the survey that most of the approval is expressed by residents of small towns, who have a secondary education, low income or the unemployed. They receive information through pro-state media (there is practically no other media left in Russia). Respondents with higher education, living in large cities, with a relatively high income, who receive information via the internet, are the least likely to approve of Putin’s moves.

In addition, there are many Russian youth among those dissatisfied with Moscow’s actions. More than 30 per cent of respondents aged 18 to 30 called the military operation “wrong”, while 47 per cent approved it. The approval rating was higher in other age groups.

Curiously, over the past two weeks, anxiety in Russian society has increased by more than 10 per cent.

Those who are dissatisfied with the actions of the Russian authorities periodically go to rallies demanding an end to hostilities. However, the authorities not only do not listen to them, but, on the contrary, transfer any speech demanding an end to the war into the category of violations of law and order, up to a criminal case. More than 5,000 people were detained at anti-war rallies held in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Vladivostok, Yekaterinburg and Novosibirsk (about 70 cities in total) on March 6. The police carried out arrests harshly, with the use of physical force and truncheons. In addition, the detainees reported that they were beat up and threatened with murder.

As participants in anti-war demonstrations say, “We do not understand why we are being detained. Russia has always stood for peace, and suddenly, for calling for peace, we are arrested, beaten, threatened and fined!”

According to the hastily adopted amendments to Russian legislation on March 4, “Public dissemination of deliberately false information about the use of the armed forces” (that is, the publication in the media or social networks of information that the Russian authorities believe is unreliable) can result in up to 15 years in jail.

For “public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the armed forces of the Russian Federation in order to protect the interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens and maintain international peace and security”, a fine of up to 50,000 rubles (more than 360 dollars at the current exchange rate) is due from an individual. In case of repeated violation, the jail term could be up to five years. Everyone who goes to rallies against the war falls under this article.

In addition, those “calling for sanctions against the Russian Federation” could be fined up to 5,00,000 rubles (more than $3,600).

It is still difficult to understand how much the unprecedented sanctions imposed by many countries have affected Russia. A number of international brands closed their stores, but only a rather small portion of the population ever shopped there anyways. Mid-tier and lower-end stores are still selling old stock. True, judging by the words of businessmen, such reserves will not last long, and banking sanctions have already made it almost impossible to pay for new foreign supplies.

To pay for goods, Russian companies are urgently looking for workarounds. Among them, payment in rubles or Bitcoins, as well as the conclusion of contracts for supply through Kazakhstan, which is part of the customs union with Russia and Belarus, but did not fall under sanctions. Russia is also negotiating with some countries, including India, on the sale of oil to them at a 25 to 27 per cent discount, subject to payment bypassing the SWIFT banking system of international payments.

An interesting detail—many ordinary people on the streets of Moscow are beginning to blame the current difficulties on the European Union and the United States. For some reason, they forget that the sanctions were imposed due to the outbreak of hostilities by Russia in Ukraine.

Optimists in Russia hope that the sanctions will lead to an explosive growth in development and production at home in everything from agriculture to space. Putin signs orders on benefits for various industries almost daily. But it remains unclear how domestic goods would suddenly appear, goods which could not be produced in the last 20 years? And who would set up production in a country where the purchasing power of the population is rapidly falling, and many representatives of big business are trying to leave Russia, fearing nationalisation?

Under these conditions, many people in Russia prefer to close their eyes and believe Putin’s words that the country will come out of the current difficulties “renewed”. “We do not know how this is possible, but we believe that Putin has a plan. For example, China will support us,” they say.

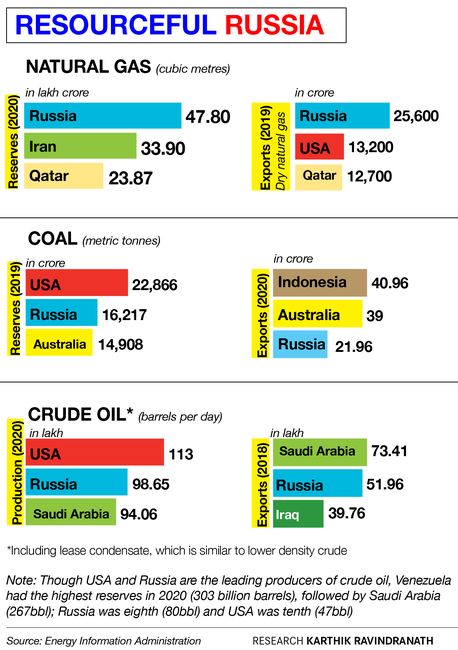

Perhaps, their optimism is justified. Sanctions may indeed turn out to be short-lived, since they harm not only Russia, but also the countries that impose them. Oil and gas prices have skyrocketed, and according to the forecasts of the Russian ministry of energy, in the event of refusal to buy oil from Russia, the price per barrel of crude could rise to $300 internationally. A grain shortage is also expected. Russia contributes to the world market about 19 per cent of the total volume of wheat and a significant part of other grains. It also supplies Europe with about a quarter of its nitrogen fertilisers, plus natural gas and ammonia, two components needed for fertiliser production. If the sanctions continue, the deficit may also affect many other industries, including high-tech ones, since Russia occupies an important place in the supply of a wide variety of natural raw materials to the world market.

The economic impact of sanctions against Russia is already severe, the International Monetary Fund said, with prices for energy and commodities, including wheat and other grains, rising sharply. This exacerbates inflationary pressures caused by supply chain disruptions and the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Western analysts, for example from Morgan Stanley, believe that Russia may become bankrupt as early as mid-April, when it would have to pay bond coupons. However, in Russia in 1998, there was already a sovereign default on bonds, but the situation has improved.

In the meantime, optimists believe that the sanctions will not have such a strong impact on the Russian economy. And those who try to think more objectively hope that the country will be able to hold out until July, and before then something will happen—either sanctions will be lifted or aliens will arrive.