Of medium height and wiry build, Vikram (name changed), all of 50 summers, looks young for his age. He leads a core team of 15 engineers and technicians on the Kaveri programme. Mostly confined to the high-security 64-acre campus of the Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) in Bengaluru—home to 240 scientists and 400 technicians, working 24/7—Vikram has spent the last 27 years on this machine and its derivatives.

“When a baby cries, the mother understands,” he says. “Till a few years ago, we did not understand the language, now we understand it perfectly. I talk to the machine and she talks to me.”

This “man-machine” talk is natural after two decades of daily tinkering with the 3.92-metre-long, 0.75-metre-broad structure inside GTRE’s main assembly hall. It has become Vikram’s life, his mission.

The basic principle of a jet engine is simple: air is sucked in, compressed, passed into rotors, multiplied (21 times in the Kaveri’s case) and released, creating thrust. But the biggest challenges lie in rotor design and in cooling turbines that run at more than 1,400 degrees Celsius.

Asked about a working day, Vikram explains: “A day begins at 8am when we assemble and plan. At 10am the teams disperse and begin work on prototypes. All conversations are technical. From 2pm-4pm we meet again to take stock. Sometimes the engine performs as per expectations or even beyond and sometimes it doesn’t as we keep on trying things. At 4:30pm we plan for the next day. But from about 4pm to 8pm, how long we stretch our time is an individual choice.”

A lady scientist chips in: “There can be no research if we keep looking at the clock.”

At first sight, the Kaveri resembles the trunk of a banyan tree that has been crudely cut at both ends. But with its mechanical contraptions and wires, it is one of the most complex machines India has attempted, holding 20,000 components including 3,000 varieties of parts.

Originally meant for the indigenous light combat aircraft (LCA), the Kaveri now lives on in the Kaveri Derivative Engine (KDE) and related programmes. On it rest the hopes of 146 crore Indians—tales of joy and dismay, success and failure.

One such tale is how lessons from Kaveri are being used for India’s stealth aerial combat platform. Its prime role: deep-strike, precision-guided, high-risk missions. Unlike the LCA’s afterburner engine (85 kilonewton thrust), the unmanned aerial vehicle is like a subsonic aircraft and needs no afterburner, operating with 49kN thrust and advanced digital controls. The unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) aims for Mach 0.9 speed, altitudes up to 13,000m and two-hour endurance. GTRE director S.V. Ramana Murthy told THE WEEK that the afterburner not being required, among other capabilities, gave it the stealth dimension. “That is one of the fundamental differences with the fighter aircraft engine,” he said. “That is why we call it a derivative engine or a dry engine.”

Sanctioned in 2018, the UCAV project is nearly complete, with 75 per cent commonality with Kaveri. Being a stealth platform, it has serpentine air intake (curved to conceal the fan face) and the resultant inlet distortion is tackled by a distortion-tolerant fan. The UCAV has also demonstrated unrestricted throttle response.

Other derivatives of the Kaveri programme include the Kaveri Marine Gas Turbine for naval propulsion, with high acceleration rate, high speed and low preparation time, and a turbocharger for armoured fighting vehicles being developed at the Combat Vehicles Research and Development Establishment in Chennai.

The multiple derivative technologies of the Kaveri have demonstrated the value of sustained R&D investment in core engine technology, points out Air Marshal Ajay Kumar Arora (retd), former air officer-in-charge maintenance, the Indian Air Force. “R&D invested in aero engines can boost civil aviation, energy, materials science and manufacturing technologies,” he says. “The aerospace engine industry can create high-value manufacturing jobs, drive innovation in metallurgy and advanced materials and develop precision manufacturing capabilities.

“The supply chain can create multiple order effects through several industries, from specialised alloys to sophisticated electronics and control systems.”

An indigenous engine also cuts dependence on foreign suppliers who can choke the supply chain and maintenance lines during conflicts or diplomatic tensions. For instance, the delay in the supply of General Electric F-404 engine is one of the main reasons for delays in LCA production, impacting the IAF’s operational preparedness.

So, even as the KDE and the lessons from the Kaveri programme are being put to good use, India is also on the hunt for an engine to power fifth-generation fighters.

Ramana Murthy said that they are working on a 120kN thrust engine for fifth-gen fighters. “The technologies are several notches above the fourth generation in thrust-to-weight ratio, turbine temperature and life—2,000 hours and all,” he said. “We want to collaborate with an international engine house (IEH).”

Aero engines are the heart of a fighter, requiring high thrust, small size and low weight, low fuel consumption, long life, high reliability and safety margins. “This knowledge base (the technology needed to meet such requirements) is developed over the decades with huge investments and become the intellectual property of a few IEHs,” said Ramana Murthy. “Military engine technologies are strategic in nature. Hence the IPs are closely guarded and there are entry barriers for others.”

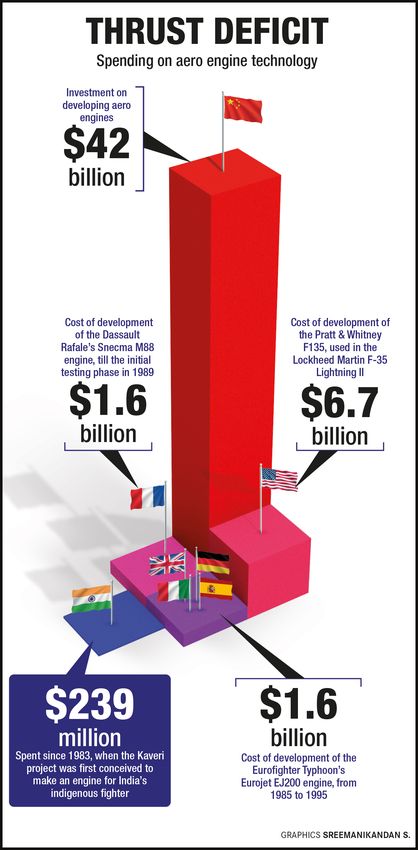

Since 1983, when the Kaveri project was first sanctioned, it has cost the exchequer around $239 million. At present rate, that converts to nearly 2,000 crore—a pittance compared with what Americans, Russians, Europeans and Chinese have invested in aero engine technology.

For instance, the development of the Eurofighter Typhoon’s Eurojet EJ200 engine cost $1.6 billion from 1985 to 1995. The Dassault Rafale’s Snecma M88 cost $1.6 billion till the initial testing phase in 1989. The Pratt & Whitney F135, used in the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, was developed at a cost of $6.7 billion. And, China has invested a staggering $42 billion on developing aero engines.

Former GTRE director C.P. Ramanarayanan said that compared with the 1980s the economic growth had increased affordability and spending capacity for funding for R&D projects. He added that appreciation of the scale of progress and challenges faced by hi-tech R&D projects were lacking in the higher echelons of government and by finance authorities. “They tended to equate progress measurement like that of road construction,” he said.

India’s dream since 1983 has been a supersonic fighter flying with a home-made engine. India had earlier built the HF-24 Marut at the state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, under the watch of German aeronautical engineer Kurt Tank. It was first flown in 1961 and inducted into the IAF in 1967. But under-powered by the British Orpheus 703 engine, it never crossed Mach 1 despite being intended for Mach 2. About 147 were operated, including 18 two-seater trainers. It saw action during the India-Pakistan war of 1971 with the most notable being in the Battle of Longewala in a ground attack role. But it was clear that the aircraft was already becoming archaic and, by the 1980s, it was phased out.

“The Marut airframe was capable of supersonic performance, but the engine limitation meant that the aircraft never reached full potential and retired early,” said Arora. “Other IAF fighter fleets like Hunter, Jaguar, MiG-27, MiG-21, Su-30, Hawk and Mirage-2000 all have faced challenges in their life cycle due to not having indigenous aero engines.”

While the home-grown fighter LCA ‘Tejas’ has made it to the skies, India had to ink a deal worth 5,375 crore in 2021 for 99 GE F-404 aero engines to power the Tejas Mk-1As. That dependency was a point in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Independence Day speech this year. “Should the jet engine for our Made in India fighter jets be ours or not?” he asked from the ramparts of the Red Fort. The nation’s answer would have been a clear “yes”. After all, the air force scenario in the neighbourhood is changing at breakneck speed. With the last two MiG-21 squadrons (comprising 16-18 aircraft) slated to be phased out in September, the IAF fighter squadron strength will plummet to just 29, much lower than the mandated 43.

Meanwhile, China fields over 83 fighter squadrons and has deployed fifth-gen J-20s near Indian borders, while also flight-testing a sixth-gen “J-36” believed to be loaded with AI, advanced stealth features, networked warfare capabilities and cutting-edge weapons. Pakistan has 20 squadrons and reportedly awaits 40 Chinese J-35s. The J-35 is China’s second fifth-generation fighter.

Developing a fully indigenous fighter engine takes 15-20 years. “IAF does not have that kind of time,” said Arora. “Alternatives need to be adopted.” So, while developing indigenous capabilities, India is also pursuing technology-transfer deals. “HAL and GE Aerospace are going ahead for a technology transfer (up to 80 per cent) agreement to produce F-414 engines in India, which will help build local manufacturing capabilities and expertise,” he said. “India and France have agreed to jointly develop a fighter jet engine based on the Rafale M88 engine for the indigenous Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft programme.”

India’s strategic autonomy demands technological autonomy; but, no IEH will share its core technology. The only answer is indigenous development. So, the effort continues, though sights are now set on sixth-generation fighter technology more than fifth-generation.

The Kaveri’s worst moment came in September 2008 when it was delinked from the LCA and funding stopped, for failing to meet weight and thrust conditions. But, in a way the project was doomed from the beginning. It had suffered from flawed planning, lack of a final design and no early provision for altitude or flight-test bed trials. All this, added to subsystem and component shortages and lack of technical knowledge and trained manpower, led to inevitable delays. As a result, the initial probable date of completion (PDC) of December 1996 was missed. Crippled by lack of domain knowledge, beset by failures and stonewalled by bureaucracy, the PDC kept on being pushed back—to December 2004 and then to December 2009.

In recent years, the massive changes in warfare have led to greater focus on UAVs—both armed and unarmed. This has been evident in the US drone strikes since 2015 to take out individual targets, in the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict in 2020 and in the prolific use of UAVs in Ukraine and Israel.

This renewed focus has been a shot in the arm for GTRE’s KDE. On the way forward, Arora said: “What India needs urgently is an apex leadership driven, government-funded, consortium-based, time-bound programme that brings together an existing aeroengine OEM (original equipment manufacturer) like Safran, GE or Rolls Royce; DRDO R&D labs like GTRE; DPSUs; the private sector; enthusiastic startups and academia together. The consortium could start with an existing baseline aero engine like F-404 or M88.”

Also Read

- The helicopter engine to be built by Safran-HMT joint venture has massive potential for export: R. Madhavan, former CMD, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited

- Mastery over core engine technology will open multiple avenues of utilisation: Air Chief Marshal V.R. Chaudhari (retd)

- Kaveri programme has led to development of Kaveri Marine Gas Turbine and a military-grade turbocharger for an armoured platform, says Dr S.V. Ramana Murty, director, Gas Turbine Research Establishment, DRDO

- Operation Sindoor caused a significant paradigm shift from manned systems to unmanned systems, says Dr K. Rajalakshmi Menon, DG (Aeronautical Systems), DRDO

This, says Arora, is probably the best way to cut short the development time and make the dream of indigenous aero engines come true in a reasonable time frame of five to 10 years.

A key issue is also the capability of the country to absorb foreign technology. Says K. Rajalakshmi Menon, director general of aeronautical systems at the DRDO: “In any collaboration, it is only equal partners or people with equal capability who can partner.” Today, she says, India is in such a position that people are coming to us with respect. “Because,” she said, “there are engine houses who have evaluated and assessed our capabilities, and have proclaimed, yes, India has got a maturity level to take up higher engine capabilities, design and development.”