DELHI

Reformer, rebel, role model—Mary Roy was many things to many people. But to her students like me, she was more than the sum of her parts. While others described her, we experienced her. We feared and admired her in equal measure. We would do anything to please her and anything to avoid her ire. Her smile could super-charge our day; her wrath could smash it to smithereens. She could walk out mid-way through a song you sang or a play you staged without a backward glance. Or the weather forecast in her fiefdom that day might be sunny, and she would be all warmth and affection. My brother remembers clambering on to her lap as a child while watching the horror film Jaws in her house. (I don’t think I would have ever dared to do that, no matter how afraid I was. No shark, for me, could be as scary as The Lap.)

But if you wanted to explain Mrs Roy, you had to visit her school—Pallikoodam in the town of Kottayam in Kerala. It was an extension of her; the instruction manual that explained the machinery of her mind. Her school was something else, its brick jaalis ventilating the dreams of hundreds of her students. As in the musical The Sound of Music (which, incidentally, we once staged in Pallikoodam) there were no ‘raindrops on roses or whiskers on kittens’, but there were many favourite things—Duckback raincoats rendered useless during afternoon rain walks, cross-country races with glucose-and-lime pit-stops, white canvas shoes in which you sleep-jogged during early morning PT sessions, kit inspections on Sundays, Nancy Drew detective novels read from end to beginning… the cargo of a childhood that, at the time, seemed to have no expiry date.

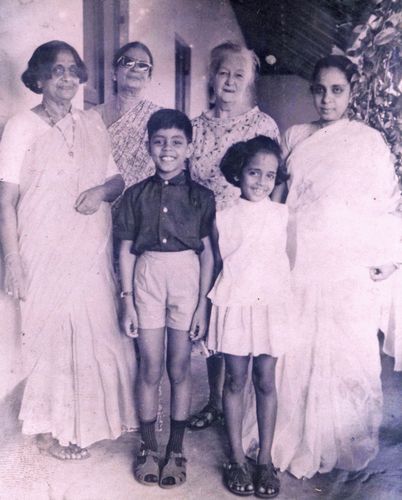

But while Mrs Roy was building her legacy through us, we never knew that there was collateral damage, in the form of two scrawny kids for whom rejection had become so much the norm that an act of kindness would feel like an aberration—Mrs Roy’s children, Arundhati and Lalith. “It was as though for her to shine her light on her students and give them all she had, we—he and I—had to absorb her darkness,” Arundhati writes in her new book, Mother Mary Comes To Me, which is more a war manifesto—an invisible battle that she is waging on the page to get at the core of what it means to be her mother’s daughter—than a tribute to Mrs Roy.

Arundhati, for instance, recounts the time when she was nine years old in 1969, and Mrs Roy had installed a telephone in the school hostel where they were staying. After the man who instals it leaves, Mrs Roy dials a number. Arundhati cannot believe that her mother is actually speaking to someone who is not in the room. Fascinated by the object in front of her, Arundhati presses a button and the call gets disconnected. Mrs Roy’s eyes turn cold. “You bitch,” she says in front of everybody. “I didn’t know what that meant, but it sounded bad, the way she said it,” writes Arundhati. “Once again, I swirled like water down a sink and disappeared. I have tried hard to forget this moment—more because of the expression in her eyes than the word itself—but clearly, I haven’t succeeded.”

It has been years since the wounds have healed, and the scars, for Arundhati, became the signposts leading to freedom.

***

We meet Arundhati at her apartment in Jor Bagh, an upscale part of Delhi. She looks very boho chic in a loose green kurta and clashing red kolhapuri chappals (you know something has gone terribly wrong in the world if Arundhati ever matches her clothes to her shoes). Her apartment is artfully cluttered, as though every displaced item is there by design. Still, there is a rustic charm about it—in the bouquet of white flowers and the lit candle on the dining table, in the rough-hewn furniture and the potted plants on the balcony, in the wooden rocking chair and the earthy red floor. Her two dogs, Marty and Begum, strut about as though they own the place.

And there are books everywhere—on the shelves, the sofa, the table, the floor. It is almost as if you can hear the sound of their breathing. If a person’s reading taste tells a lot about them, Arundhati’s only deepens her enigma. There are all sorts of biographies. Her book shelf is probably the one place where the heroes and villains of history tip a hat to each other. Stalin and Hitler jostle for space with Van Gogh, Tolstoy and Jung. But there are also classics, science fiction and recipe books. (She says she loves cooking Kerala food. Her favourite is boiled tapioca with fish curry.)

On the wall behind the dining table is a Salvador Dali-esque wooden clock gifted to her by ex-husband Pradip Krishen, with the time permanently set at ten to two, a reference to the time on the toy wristwatch of the seven-year-old protagonist, Rahel, in her Booker-winning novel The God of Small Things. “In some strange ways Pradip’s clock was right,” she writes in the latest book. “There were parts of my life in which time stood still. It was always ten to two. Reassuring and unnerving simultaneously.”

She loves her home. Every now and then, she writes, she kisses the walls and raises a glass and a middle finger to her critics who expect her to lead a life of “fake, self-inflicted poverty”. She leads me to the sofa which she says is her favourite part of the house, almost like a womb, as she lies curled up reading a book, her dogs at her feet.

Mother Mary Comes To Me was not an easy book to write, she tells me. “I don’t think anything that is easy to write is worth it,” she says. “But in every book that I write, I look for language. What should be the tone, the idiom? Because this book deals with a lot of tangled, thorny things, the way it is written is deceptively simple.”

I ask her whether there is anything in the book she could not have written while Mrs Roy was still alive. “From the time I was very small, she was very different with us than she was with her students,” she says. “There was no question of us ever saying anything to her. There is nothing in this book that I have actually talked to her about. There was never a possibility of me responding to her about anything. We were not allowed to do that. So, this book is my response.” Arundhati says she wrote it because her mother is a woman that needs to be shared with the world. “She belongs in the pages of literature and history,” she says.

Afterwards, she orders chicken and cucumber sandwiches for us while finalising the details of her upcoming book launch in Kerala with someone from Penguin. She is very specific about what she wants—from the lighting to the seating arrangement to what the screen behind the stage should say. “It sounds just like planning a wedding,” jokes my colleague. “Yes, a wedding without a bridegroom, which is the best kind,” says Arundhati with a laugh. It is a soft, summery laugh—intimate, as though she is letting you in on a secret. The impression is deceptive, because there is steel beneath the softness. At first glance, you might think that she is her mother with the edges mellowed—a kind of Mrs Roy Lite. In which case, you would have thought wrong. She is just as strong and tumultuous. She is the storm inside the calm.

“My mother was a very volatile person and I am the exact opposite of that because I was trained from the age of three that you cannot respond to her,” says Arundhati. “I’m not somebody who easily yells and screams, but I think we both have the same ability to say no, just in different registers.”

And then she delivers the punchline: “Her greatest gift to me was an overactive middle finger.”

***

In the summer of 1978, when Arundhati was 18 and a student of architecture in Delhi, she left home for good. “I left my mother not because I did not love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her,” she writes in the book. There was barely any money and it was a hand-to-mouth existence, the survival of the weakest. She did not even have a place to live. For a while, her boyfriend and she squatted in the storeroom of their architecture school; she used the men’s toilet on the fourth floor. Later, they got upgraded to a tiny shanty colony near the ruins of the 14th century fortress Feroz Shah Kotla. It had community toilets and open drains into which children practised aiming their shit, she writes. It was a time of unceasing anxiety about money. The vagrant life looks glamorous only in paperback novels.

After she graduated as an architect, she found a temporary job at the National Institute of Urban Affairs, and that was when life threw an Eric Clapton-shaped curveball at her. That is what she thought he looked like when she first saw him—Clapton in John Lennon glasses. Pradip Krishen was a botanist, filmmaker, historian, swimmer and tennis player. In other words, a buy-one-get-all-things-free package deal. She met him through his wife who was her boss at the national institute. He offered her a role in his film Massey Sahib, shot in and around a small, forested hill station called Pachmarhi in central India. “The shoot was scheduled for the winter of 1982,” she writes. “I went into it motherless, fatherless, brother-less, jobless, homeless. Reckless.” The two started an affair, what she calls a fling for him and a train-wreck for her. Massey Sahib led to In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, that Arundhati wrote and Pradip directed. Although they had never meant it to be anything more than “fun, fringe cinema”, when it finally showed on Doordarshan, it got an audience of millions and won two national awards, including for best screenplay.

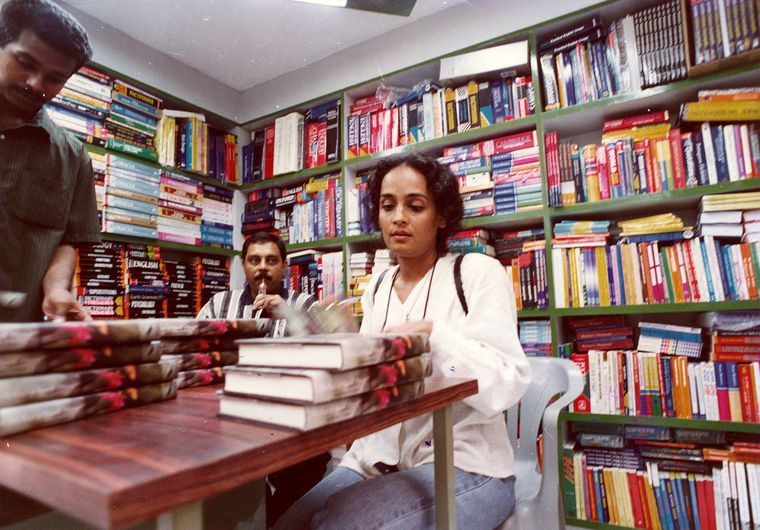

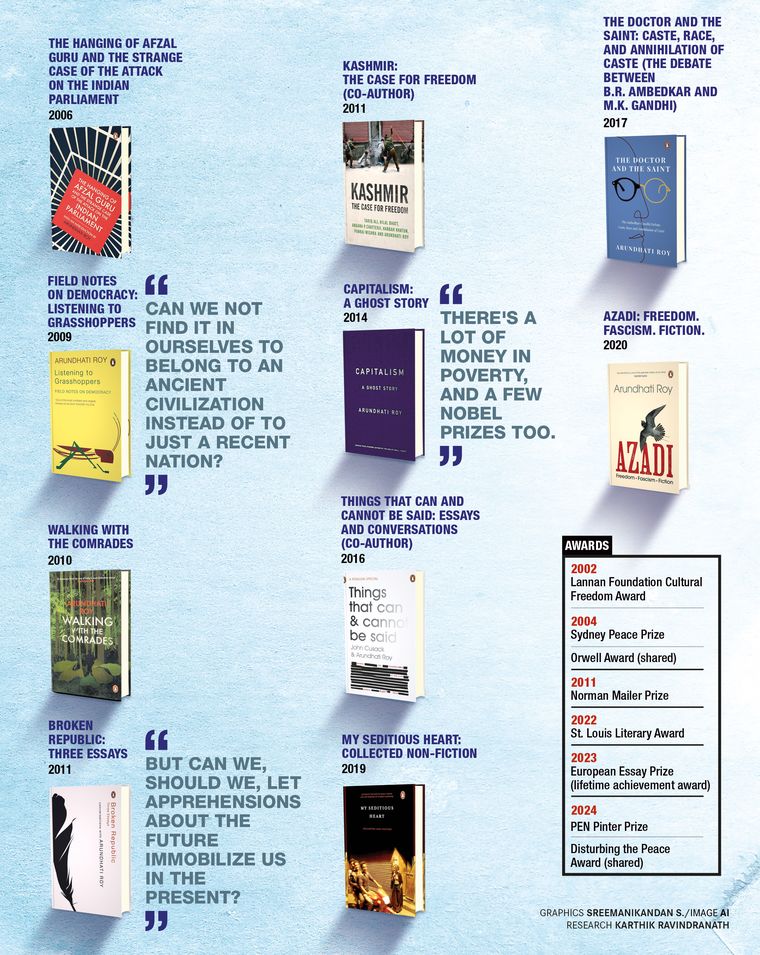

And then came the final act in her life of waning anonymity—a book that at once set her free and shattered her freedom: The God of Small Things. It was published in 1997, when Arundhati was 36 years old. For a while after it won the Booker Prize, she was the blue-eyed girl of India. It was a role she loathed, so much so that when she published her first political essay, The End of Imagination, on the ramifications of India detonating three nuclear devices in Pokhran, the reaction to it—which was almost as explosive as the bombs themselves—came as a relief. “It liberated me and set me walking,” she writes. “For years after that I wandered through forests and river valleys, villages and border towns, to try to better understand my country. As I travelled, I wrote. That was the beginning of my restless, unruly life as a seditious, traitor-writer. Free woman. Free writing. Like Mother Mary taught me.”

Soon, her identity became hyphenated: writer-activist. It was a term she found absurd, because it suggested that writing about things that impacted the lives of others was not the job of a writer. “To me, ‘writer-activist’ sounded a bit like a sofa-bed,” she writes. She is not angry at the appellation; she is almost amused by it. Her ridicule is twice as lethal as her rage.

***

Surprisingly, Mother Mary Comes To Me is not about venting, just as it is not about veneration. Unlike us, Arundhati was never one of Mrs Roy’s groupies; after all, she lived in the black hole of her mother’s cruelty. Yet, there is pathos in the book. The defiance and non-conformity of its protagonists are obvious; their humanity lies in waiting. The writing is witty, but the humour hides a wealth of pain, longing and haunting beauty.

The book is neither an excuse nor an explanation; it is merely a vantage point to a person too complex to be called either saint or sinner. Mrs Roy wouldn’t have stood for it; she was too badass for such simplistic definitions.

The feminists, for example, might have burned bras; Mrs Roy used it as armour. It happened in the early years of the school. When it was brought to Mrs Roy’s attention that boys in the hostel had begun to tease the girls about breasts and bras, she held a special assembly. She sent two of the bullies to fetch a bra from her cupboard. Hers looked sizeable in the hands of the two frightened boys, writes Arundhati. “This is a bra,” she told the students. “All women wear them. Your mothers wear them, your sisters will too, soon enough. If it excites you so much, you are welcome to keep mine.” According to Arundhati, it was one of those moments that changed the balance of power between boys and girls in the school forever.

Mrs Roy also gave her daughter the greatest gift: language. She instituted something called ‘free writing’ in her school. From the time Arundhati could hold a pencil, she encouraged her to write what was on her mind. She even preserved the paper on which Arundhati had written her first sentence. It was about Miss Mitten, an Australian missionary who was her teacher when she was five years old. In a mathematics class, she gave Arundhati a sum that involved counting up to more than ten. When she wasn’t looking, Arundhati took off her socks, counted on her toes, then put the socks back on. Miss Mitten demanded to know how she got the sum right and refused to believe her when she insisted she had done it in her head. She told Arundhati that she was wicked and she could see Satan in her eyes. Later, Mrs Roy asked her to write what had happened at school that day. She wrote: “I hate Miss Mitten. Whenever I see her I see rags. I think her gnickers are torn.”

No one, least of all Arundhati, could have guessed that the seeds of her calling lay entangled in an Australian missionary’s lingerie.

***

As we are having the sandwiches, my colleague asks Arundhati whether she is still learning Hindustani classical music and how difficult it must be to master it. “Well, it is only difficult to master if you want to perform on stage, and that was never my intention,” says Arundhati.

Just like her mother, Arundhati is determined to never stop learning. Then she mimics the lines of a Malayalam poem about a mosquito that Mrs Roy used to falteringly recite to teachers and old students when they visited her, as she was learning to read and write Malayalam in her 80s.

Mooli pattu paadi varunnoru

chora kudiyan kurukomban

(Here he comes with his harmless hum, that bloodsucking little tusker)

Until the day she died, she never stopped learning, never stagnated, never feared change, never lost her curiosity, writes Arundhati. Mrs Roy could be cruel, but she could also be playful. Once, when a journalist asked her if she had indeed had a tragic love affair like the character of Ammu in The God of Small Things (who she believed was modelled after her), Mrs Roy shot back, “Why? Aren’t I sexy enough?” She was in her 60s then. Many years later, Mrs Roy’s bath would become an elaborate ritual undertaken by a carefully curated bathing team. If Arundhati was visiting, Mrs Roy would often send for her. “Would you like to watch your mother being bathed?” she would ask. “Why don’t you take a photograph?”

“Ok,” Arundhati would reply. “I promise not to show it to anyone.”

Mrs Roy’s response was priceless. “Then what’s the point?”

If her life was tumultuous, Mrs Roy made up for it with her death—a peaceful, even perfect, one. She was 89 years old. On September 1, 2022, Mrs Roy changed into fresh clothes, ate a good breakfast, and then lay down on her bed and died. No one would even have known she was dead if she hadn’t been lying on her back, writes Arundhati. She never lay on her back, only on her side.

On her headstone, they wrote: “Mary Roy, Dreamer Warrior Teacher. Founder Pallikoodam.” It would never have occurred to her children to write the usual stuff: wife of so-and-so, mother of so-and-so. “She would not have liked that,” writes Arundhati. “Those were not the stripes she had strived to earn.”

To understand Arundhati, you need Mrs Roy. Not because they are cut from the same cloth. The daughter is not a continuation of the mother. It is more a cause-and-effect relationship. One is the reaction to the other. Still, they don’t make them quite like these anymore. They are quite the pair.

The woman and her wild-child.

The storm made real in the storm rider.

Mother Mary Comes To Me

By Arundhati Roy

Published by Penguin Random House India

Price Rs899; pages 376