ARARIA, MADHUBANI, GAYA

Agroup of undernourished kids, with their naked bellies out, run through the dusty lanes of Bhawanipur in Bihar’s Madhubani district. Around them stand small, sun-baked mud-brick structures sheltering their lonely mothers who are watching over them. The men have been away for months. “My husband has been working in Kerala for five years,” says Savita Devi, 30, sitting cross-legged in her house. “He sends money so we can feed our three children.”

Savita last saw her husband seven months ago. THE WEEK met more than two dozen women in the village with the same weary tale of families fragmented over sustenance and survival. “Almost every family in the village has a husband or a son working outside Bihar,” says Narendra Singh, who facilitates the migration to other states, “so they can earn some money and feed their families back home.”

And this is what the newly formed Jan Suraaj party has tailored its campaign on, with an electoral cry of protecting the state’s cultural identity and its tiniest unit in society―the family. Bringing back migrant workers and giving them jobs nearby is party chief Prashant Kishor’s pitch to the masses. But the party’s election promises haven’t reached Bhawanipur yet. Kishor is busy rolling out his campaign some 200km away in another remote corner―Palasi village in Araria district.

Here, thousands of people have gathered to hear Kishor on a hot summer evening. He makes his way through the crowd in a white kurta-pyjama, with his party’s yellow flags fluttering around like flames. He steps onto a raised platform, waves his hand, and confidently calms the crowd down. “I have not come here to seek votes,” he says, his face soaked in sweat, “so listen to me for 15 minutes without clapping.”

He then lists three things that he thinks have stagnated Bihar’s growth―unemployment leading to migration, insufficient education and lack of financial care to the elderly. “Voting for the Jan Suraaj will protect the future of your kids, so vote for your kids this time,” says Kishor, who hails from Konar village in Rohtas district. He then taps the local sentiment with the “us first” policy of his party. “When I say Jai Bihar, you repeat Jai Jai Bihar.” The crowd erupts, loudly repeating the slogan.

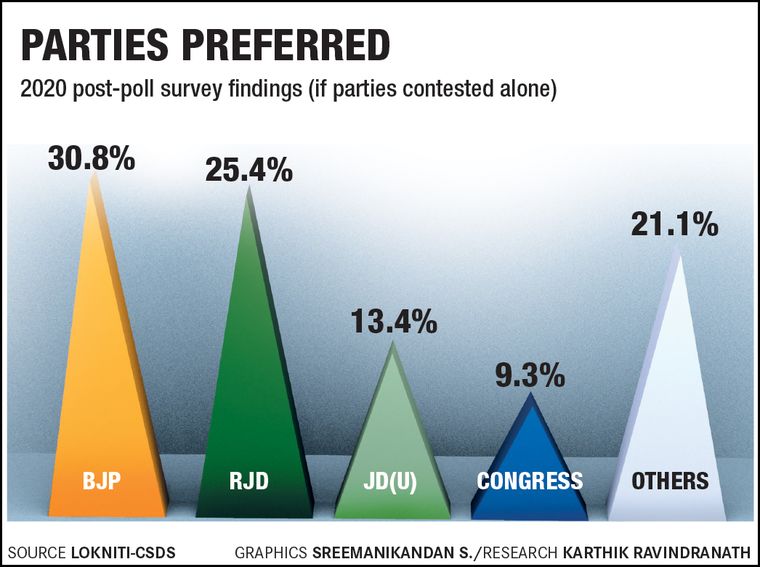

In the last few seconds of his speech, Kishor rolls out his political message, positioning the Jan Suraaj (which means good governance for the masses) firmly as a third front between the two dominant political forces―the National Democratic Alliance, led by the BJP-JD(U) combine, and the Mahagathbandhan, led by the RJD and the Congress.

Kishor seems to have found a connect with the villagers, at least in that moment. “For the first time, someone is talking about our suffering,” says Chandan, 47. “We feel he can change Bihar.” But as a police officer managing the crowd says, “In Bihar, it is easy for anyone to gather thousands. If Lalu Prasad comes here, thrice the crowd will come to hear him and go back home impressed.”

The path to victory is indeed long and demanding. Kishor skipped breakfast and left early that day to fix operational blips in his party and make timely appearances in public gatherings. “He stayed hungry the entire day,” says Uday Singh, national president of Jan Suraaj. “Despite that he managed to passionately address the public.”

Kishor, who founded the Jan Suraaj in October 2024, holds two such mass gatherings a day, on an average. “The campaigning started with the onset of June,” says a young leader in his team. “Kishor is the only politician in Bihar who started campaigning so early.”

Known in Delhi circles as a man with the Midas touch, Kishor has scripted massive victories―first helping the BJP win the 2012 Gujarat assembly elections and the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, followed by spearheading winning electoral campaigns of different parties across states like West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh. As a political strategist, he has been near flawless, but his strategy as a politician will be tested this time.

People who have worked with him say that he operates with a well-mapped-out strategy. So to connect across religions and castes, Kishor is selling a “development agenda”, sensing an urgent need for it after reportedly travelling on foot to 5,000 villages. The poor would be the primary beneficiaries, he says. The key question now is whether Kishor can secure a substantial share of votes. The ground realities remain a puzzle. Though Kishor’s cry of badlaav (change) in Bihar have stirred many, a majority of them pledge loyalty to their caste leaders. In several pockets across north Bihar, a considerable section of dalits steadily back the Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas), led by Chirag Paswan. “He is our hero because he comes from our caste,” says Dharmendra Paswan from Bhimpur village of Supaul district, adding that there are 2,200 Paswans in his village. “We will only vote for him and nobody else.”

But Kishor is defiantly trying to wade his way into the caste-centric politics of Bihar, hoping to change it from within. In a conversation with THE WEEK, he dismisses the argument that Bihar’s politics is centred on caste, saying it is only one of the factors that influence the election. Of course, sops, money, alcohol, family needs and influence of the family head figure, community leaders and village chiefs who can rally half the village in support of a party, play a crucial role in influencing poll outcomes. However, the reality is that most voters pivot around caste when they step out to vote. Take, for instance, Ravindra Kumar Palasi, an autorickshaw driver in Narpatganj, Araria district. “We will first see the candidate and then vote,” says the 54-year-old. “We have been voting for the BJP, but if they field someone from another caste, we will not vote for them.” The other drivers agree with him.

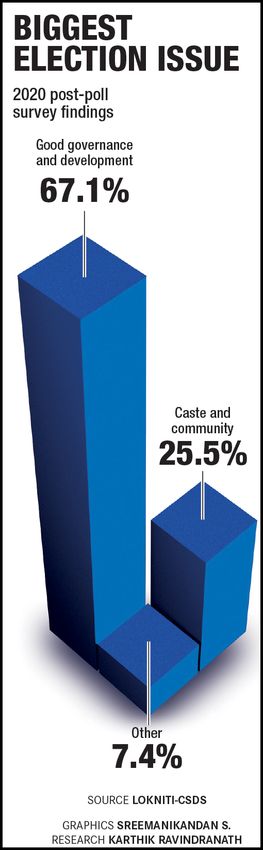

“It is not just a dominant caste mindset,” says N.K. Chaudhary, a retired professor from Patna University and political commentator, “rather it is an outcome of caste polarisation during the heat of elections. When one group becomes vocal about its caste, it invigorates people belonging to other castes. Caste polarisation happens the same way religious polarisation does.” He, however, agrees that Kishor is on a bigger mission to blur caste lines and create a new political turf in Bihar by changing the rules of the game. The plan, by and large, is to rewrite public memory to drive people to think about their own needs rather than castes on polling day.

“The first phase of his campaign has been successful,” says Manindra Nath Thakur, who teaches political studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. “But he has not been able to create that empathetic connect with people. He comes off as a manager and not as a mass politician.”

As a strategist, Kishor has helped many a political leader connect with masses. But these were leaders with an established party cadre, which his Jan Suraaj lacks. Yet his excessive media presence and ruthless social media campaigning appear to have found an audience among the discontented youth. Aditya Rathi, who tracks social media behaviour of the electorate, says that Kishor’s speeches have had a huge impact on people below 40.

“The government hasn’t done enough for us,” says Rahul Kumar, 27, who harvests makhana (fox nuts) with a group of 20 men in Jhagarua village in Purnia district. “Kishor is a truth-teller; we watch him on our smartphone.” The older men in the group were either clueless about Kishor or had a vague idea of him. The party also has poor brand recall among the illiterate population.

“We have also felt there is less brand recall of the party, but it is in rural areas where there are no smartphones and no social media,” agrees Dr R.K. Jha, the party in-charge of Seemanchal region. He also accepts the weakness in organisation, but says they are “working on it”. Another issue is the lack of second-rung leadership and popular faces and foot soldiers on the ground. “Nobody has reached out to us till now from his party,” says Chotu Singh from Forbesganj in Araria, who has returned to Bihar to tend to his agricultural land. “If they give us employment here, we will vote for them.”

For now, the Jan Suraaj is active in around 430 blocks, holding more than 800 small public gatherings every day that are being monitored by its 38 district presidents. “We are also reaching out to all those who have contested any election and are inviting them to join us,” says a senior office-bearer of the party. Moreover, the party has deployed a fleet of more than 600 yellow cars (around 15 in each district) to carry and expand its visibility.

With Kishor as the only popular face of the party, even if he addresses two public gatherings a day―with a crowd of 10,000 each―it would add up to 180 public gatherings in 90 days. The direct voter outreach would total up to only 18 lakhs, which is less than 4 per cent of the total electorate of the state. To garner a significant vote share, the party needs a major people-centric push on ground to build trust. But this can only happen in the long run and only if he wins a few seats and is able to develop them into model constituencies.

According to political observers, Kishor may focus on 20 to 100 seats, a strategy that can help him gain some ground. But for now he plans to contest on all 243 seats.

“For the Jan Suraaj, the 2025 elections are likely to serve more as a disruptive debut than a transformative breakthrough,” says political analyst Madan Mohan Jha. “The party appears poised to secure a minimum of 7-8 per cent, and at best, 10-12 per cent of the total vote share. If voter support for both the NDA and the Mahagathbandhan erodes significantly, the Jan Suraaj could potentially win between 8 to 15 assembly seats. In such a scenario, it may find itself positioned as a kingmaker.”

There are also questions about whether Kishor will ally with the BJP, given the perception of him being the BJP’s B-team. Party leaders say his campaign is designed in such a way that it cuts into the voter base of every party. Though he categorically denies going for an alliance, sources say he will be open to it only if he is offered the chief minister’s chair.

Apart from Kishor’s Jan Suraaj, there are other smaller formations that have considerable influence in some pockets of the state and are piggybacking on either the NDA or the Mahagathbandhan to join the mainstream.

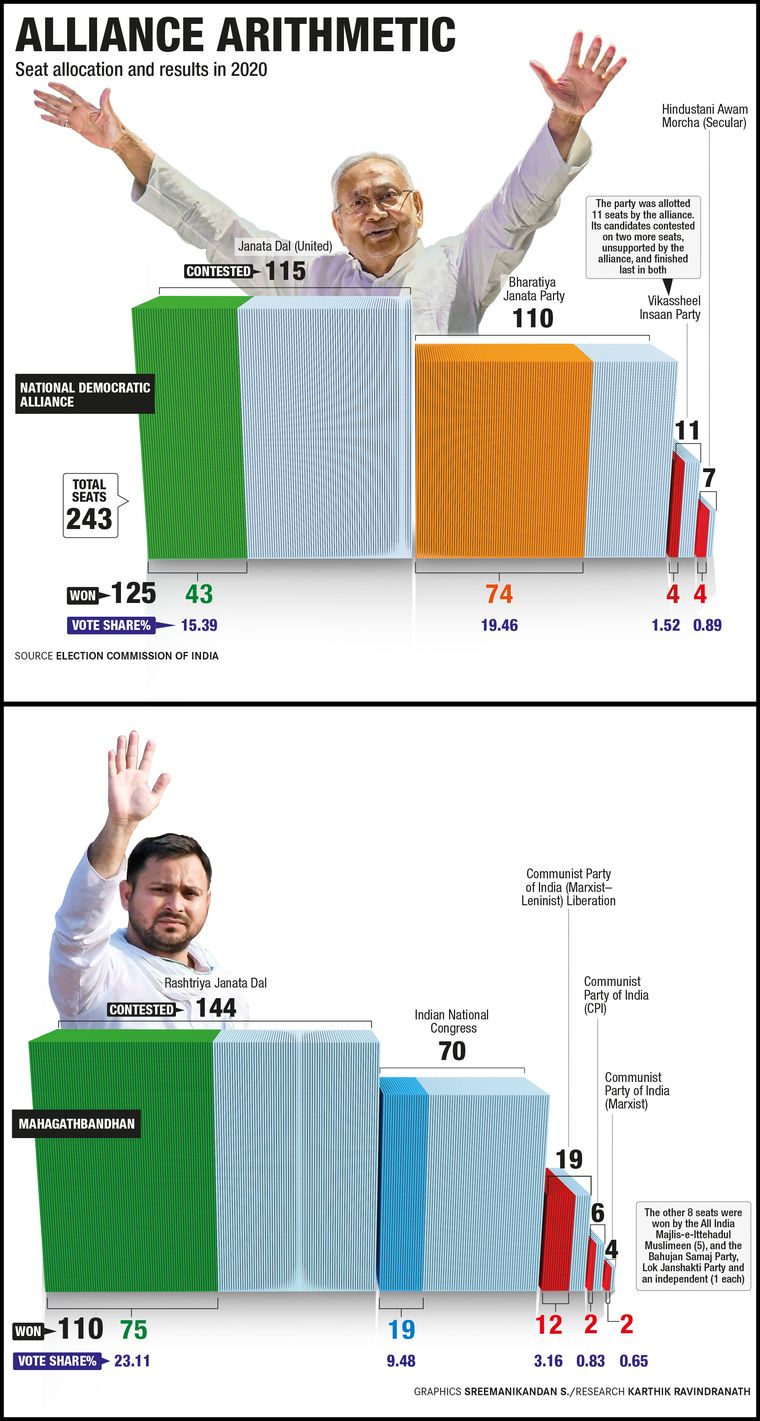

For example, the Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP), which represents the fishermen and makhana farmers (Nishad) community, would be contesting this election with the Mahagathbandhan. Launched in 2018 and having contested the first election with the NDA, the Mukesh Sahani-led party shifted loyalty towards the Mahagathbandhan after the saffron camp influenced defection of all four of its legislators in 2022. In 2020, the VIP had won Alinagar and Gaura Bauram in Darbhanga and Sahebganj and Bochahan in Muzaffarpur. These seats have an extremely backward classes electorate from the Mallah-Kewat sub-castes of the Nishad community. The VIP’s 1.52 per cent vote share in 11 assembly segments suggest that associating with his party can propel the outreach of the Mahagathbandhan and consolidate a sizeable chunk of the Nishad votes, which constitute around 10 per cent of the state’s population. The NDA can ill afford to lose its Nishad votes, and is therefore trying to bring Sahani back into the saffron fold. Sahani, however, is against a return. He is eyeing more than 40 seats from the Mahagathbandhan, which, its leaders say, he may not get.

For the NDA, these smaller parties are crucial to get the winning numbers, especially when there is an undercurrent of anti-incumbency. Add to it, there are rumours that Nitish Kumar may not come back as chief minister and the BJP is at a loss when it comes to projecting a face from the party. For now, two of its fringe allies―the Hindustani Awam Morcha, led by Jitan Ram Manjhi, and the Rashtriya Lok Morcha (RLM), led by Upendra Kushwaha―are staying put. The HAM had won four of the seven seats it contested in 2020―Imamganj, Tikari, Sikandra (all three in Gaya) and Barachatti (Jamui)―and secured a vote share of 0.89 per cent.

This time, Manjhi, who belongs to the Musahar dalit sub-caste, says his aim is to get his party recognised as a state party. “We either need 6 per cent vote share or eight legislators to get recognised as a state party,” says the former chief minister. “We will ask for around 15 seats so that we can win eight at least. On other seats, we will help the NDA.”

Meanwhile, Kushwaha’s RLM, which went solo last assembly elections, had topped the list of independent parties with respect to vote share―1.77 per cent. The party chief has a noticeable appeal among the Kushwahas (also known as Koeri), a powerful other backward classes community comprising more than 4 per cent of the state’s population. In many seats in central and south Bihar, the RLM is seen as a kingmaker when combined with the support from Mahadalits or non-Yadav OBCs.

Also Read

- ‘There is no caste-centric politics in Bihar’: Prashant Kishor

- ‘There is no space for third front in Bihar’: Upendra Kushwaha

- ‘We may emerge as second-largest force in Mahagathbandhan’: Mukesh Sahani

- 'We are prepared to contest alone or even form a third front': Akhtarul Iman

- Can Prashant Kishor overcome Bihar's political caste loyalties?

In 2020, the JD(U)-BJP combine won 117 seats, just five short of the majority. It was thanks to smaller parties like the HAM and the VIP that the NDA reached the magic number. This time, it is counting on Kushwaha and the potential support of the Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas), which had secured a vote share of 5.66 per cent in 2020.

Another key player, especially in the Seemanchal region, is the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM). Last assembly polls, it had surprisingly won five of 19 seats it contested―Kochadhaman, Bahadurganj, Jokihat, Baisi and Amour. The AIMIM win in Seemanchal dealt a significant blow to the Mahagathbandhan. In 2022, four of AIMIM’s legislators jumped ship and joined the RJD. Now with a depleted cadre base, its state unit president and the party’s only MLA Akhtarul Iman says the party won’t join any alliance.

Then, there is Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party, which had secured 1.49 per cent vote share in the 80 seats it had contested last time. Its state unit chief Shankar Mahto says that Mayawati is keenly watching the developments in Bihar and taking a daily feedback on the progress being made by the party on ground.