On the fifth floor of a grey, nondescript building in Cambodia, Sharvan hunches over a computer, sending WhatsApp messages to strangers, spinning lies about fake investments and watching as victims lose their life’s savings. The windows are sealed. Multiple screens buzz with activity under fluorescent lights that never go off. Just a year ago, the 24-year-old from Rajasthan had dreamed of joining the Army, like his elder brother. Today, his hands tremble—not from gun drills but from the fear of the next electric shock. He has become a slave—not to a factory or a field but to a shadowy empire of cyber fraud, run by Chinese agents and bolstered by trafficked youth from across South Asia, especially India.

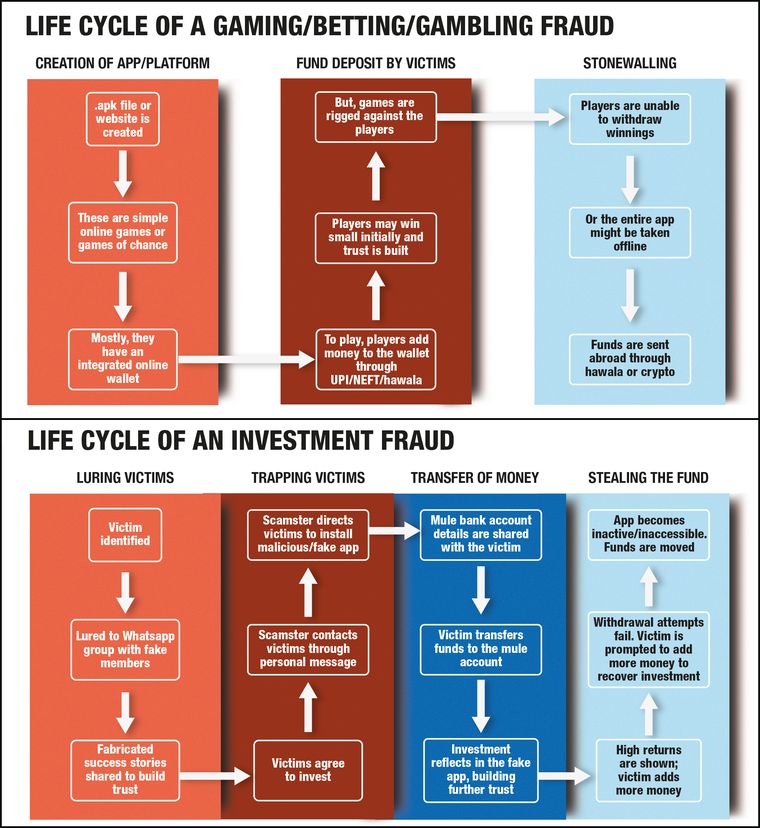

Sharvan and others are trained to create fake social media profiles to scout for victims, often posing as financial advisers or attractive strangers offering insider investment tips. Those who show interest are added to WhatsApp groups filled with those posing as successful investors. “Our job was to make it look real, with charts, screenshots and testimonials. Everything was fake. We used trading apps that mimicked real platforms. We would first let them earn a little. They could even withdraw money to build trust,” said Sharvan. Then came the bait.

“We would tell them to invest Rs5 lakh or even Rs20 lakh, promising huge returns. Once the money was transferred, we blocked them,” he said. “We had daily targets, no breaks, no compensation. We were machines. We worked on the fifth floor and slept on the fourth. Guards never let us leave. If we disobeyed, they would send us to the black room for electric shocks.” Sharvan was sold to six or seven companies.

Most Indian workers are from southern states and speak better English—they are promoted faster. Those from the north struggle more. Sharvan’s father, a farmer, spent Rs50,000 to send him to Dubai after an agent promised him a job. Once there, he was forced to pay another Rs80,000 for “legal papers” to move to Thailand and Cambodia. Sharvan travelled to Cambodia on a business visa. “They took away my passport once I landed. I had to pay $5,000 to leave. But no one could afford it.”

On April 12, Sharvan returned home, after Cambodian authorities, under pressure from the Indian government, helped connect trapped Indians to embassy officials. Sharvan’s ordeal is part of a global cybercrime crisis, and India is the first among many to recognise and act against cyber trafficking.

Working overnight to bring back Indians is the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C), leading the country’s response to cyber crime and serving as a central point for law enforcement agencies. It helps prevent, detect, investigate and prosecute cyber cases. “Union Home Minister Amit Shah places very high priority on bringing Indians back from these scam compounds and preventing new ones from reaching there,” said Rajesh Kumar, CEO of I4C. “We leverage India’s diplomatic clout and bring in the support of partner countries to ensure action. State agencies have been proactive in identifying recruitment agents and influencing families to get their loved ones back.”

The I4C, which began as a scheme within the Cyber and Information Security Division of the home ministry in 2018, has become a national nerve centre for combating the rising tide of cyber fraud across the country. The I4C has cross-sectoral visibility of cybercrimes, stringing together key components—citizens, telecom service providers, banking institutions and network service providers. It also aids law enforcement agencies in tracking and investigating cyber fraudsters and their networks through multi-state coordination, cyber-forensic capabilities and the latest software tools.

In the last three years, as many as 3,764 Indians have returned from Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Laos—some as victims and others as willing criminals. Large numbers returned in March and April this year. Most of them are from Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gujarat, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Their return is helping to expose more cyber fraud modules within the country.

In March, the Goa Police arrested Nulaxi Talaniti, a Kazakhstan national of Chinese origin, for involvement in an international trafficking ring running cyber slavery call centres across Southeast Asia. After the I4C helped bring Rakesh Murgaonkar (name changed), 24, back from Thailand, details emerged on how the entire network operates. Murgaonkar, a resident of Goa, had been chatting on Instagram when he came across a job offer from an Indian agent, Adithya Ramchandran, who had connections with the Chinese. They offered him a job in Thailand with a monthly salary of Rs60,000. Murgaonkar left Goa on January 14 and landed in Thailand the following day. He was then taken to a company in Mae Sot, on the border with Myanmar, to work at a call centre contacting potential victims. “The victims were lured to invest in fake trading companies or were honey-trapped to commit financial fraud,” said Rahul Gupta, superintendent of police, cyber crime, Goa.

An investigation revealed that Murgaonkar had met several Chinese agents during his two-month stay in Mae Sot, and one of them had even visited India in March. “After several foreign numbers running digital arrest scams were blocked, the cyber fraudsters found it harder to operate. They have been trying to set up a base in India. The Kazakh national, Nulaxi, came to India to set up a SIM box facility (a device to connect to VoIP gateways using a pool of SIM cards) with Ramchandran. He set up a SIM box in Bengaluru, which we recovered. He was arrested from the Delhi airport when he tried to flee the country,” said Gupta. The SIM box was intended for use in digital arrest scams.

A key component of the I4C infrastructure is the Cyber Fraud Mitigation Centre (CFMC), which coordinates real-time responses to online financial crimes. A lesser-known fact is that the I4C draws strength from officers and military experts who have served in anti-Naxal operations and at the higher reaches of the Line of Actual Control with China, where cyber attacks constantly accompany aggressive postures from adversaries. Amit Shah conducts regular meetings with top officials to devise detailed plans for a cyber-secure nation.

The total value of cyber frauds reported nationwide, which was at Rs2,254 crore in October 2024, dropped to Rs1,314 crore by April 2025. High-value frauds (greater than Rs50 lakh) also saw a drastic decline, from Rs1,065 crore in October 2024 to Rs402 crore in April 2025. This decline is the result of the cooperation of over 200 representatives from banks, telecom companies, payment aggregators and state police units at the I4C, monitoring over 150 real-time dashboards. The dashboards continuously analyse complaints, flag high-risk activity and trace overlapping jurisdictions.

“The I4C is a unique organisation within India’s federal framework,” said Rajesh Kumar. “Crime and police are state subjects but this is a farsighted initiative of the Union home ministry, which is dedicated to strengthening law enforcement agencies in states and Union territories as well as other wings of the criminal justice system in all possible ways.”

The I4C, for instance, has been working with the Rajasthan Police to lead a data-driven crackdown on cyber gangs operating from the Mewat region of the state. This area has been responsible for 76 per cent of all cyber frauds originating from Rajasthan’s primary hotspot—Deeg district—at the time. At the heart of this effort was Pratibimb, a software tool developed by the I4C to help law enforcement agencies track mobile numbers used in criminal activity, allowing police to pinpoint the precise locations of cyber criminal clusters. “We set up a war room that tracked these digital locations and guided police teams to the villages where cyber gangs were operating from remote, carefully chosen hideouts,” said Rahul Prakash, inspector general of police, Bharatpur Range.

The gangs used fake social media profiles—often featuring photos of women—to extort victims, while also engaging in scams such as selling counterfeit goods and offering fake hotel bookings on Instagram. During the raids, special police teams cordoned off identified areas, seizing mobile phones, lap tops and digital storage devices. The digital evidence, including chats, videos and transaction records, helped register over 600 FIRs. More than 2,000 people were arrested.

Prakash described the socio-economic profile of those arrested as mostly young men, including school dropouts and individuals in their 20s, who had acquired cyber skills through peer-to-peer learning. Despite minimal formal education, many gang members earned between Rs25 lakh and Rs2 crore per month. “We called it ‘Operation Anti-Virus’ and it underscored how centrally supported intelligence tools like Pratibimb can empower state law enforcement agencies to address rapidly evolving forms of digital crime,” he said. It also showed how cooperative mechanisms between the Centre and states are essential for tackling cyber crime in India’s rural and semi-urban regions.

One of the most powerful tools in this mission is the high-value fraud alert system at the I4C. When a large deduction is reported, an automatic alarm triggers a rapid response protocol. Bank officials, telecom providers and law enforcement agencies, all stationed on-site, begin a countdown to intercept the transfer. This is supported by machine-to-machine information sharing, which allows seamless coordination without alerting the fraudster. “As soon as the alarm goes off, the goal is to hold the money before it vanishes,” said an official. Uttar Pradesh director general of police Prashant Kumar said the I4C had helped tackle cyber scams in the state. “We have been able to launch swift crackdowns on cyber criminals in collaboration with the I4C.”

The ever-evolving threats of cyber crime require continuous training and upgradation of state police forces. According to cyber crime trends analysed daily by the CFMC, investment scams top the list in most states, followed by trading app scams, part-time job scams, KYC frauds, courier scams, digital arrest threats, instant loan apps, FedEx frauds, mystery box scams and matrimonial frauds.

“The victim often does not realise they have been duped. Fraudsters may return small profits or even show inflated balances to build trust. This can continue for days, months or years. But once we receive an alert, we focus on the last few days of the transaction. These are the golden minutes, especially when the final, substantial deduction can still be stopped,” said an I4C official. Investment scams primarily target individuals in the 25–40 age group, while digital impersonation and lure-based scams mainly target senior citizens, as they are more vulnerable to them.

On May 19, Shah announced a system that automatically converts cyber financial complaints worth 010 lakh and above registered on the 1930 helpline or the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal into FIRs. This e-zero FIR initiative has been launched as a pilot project in Delhi.

However, despite the government’s best efforts, some frauds still lead to successful cash-outs, particularly abroad. Dubai has emerged as a hotspot, where stolen funds are quickly converted to cryptocurrency via wallet transfers. These transactions are particularly difficult to trace.

The telecom sector plays a crucial role in these operations. Fraudsters often initiate contact with victims through WhatsApp, SMS or fake links, which are used to steal personal information. Said a telecom service provider at the CFMC: “The first point of contact is usually telecom services, which makes it critical for us to build a database of suspect numbers.” Once identified, state law enforcement agencies can block these numbers but tracking disposable SIM cards remains a challenge. To tackle this issue, the government is working on new guidelines that require SIM card point-of-sale locations to be documented.

Meanwhile, the RBI is urging all banks to set up cyber monitoring units and integrate with the CFMC ecosystem. “Smaller banks are sometimes used to park stolen funds. We are nudging them to come on board,” said an official. More than 500 banks and cooperatives have integrated so far. But the goal is larger: to reduce response times, onboard more private players and bring every state and Union territory into a unified defence mechanism.

This defence mechanism is being bolstered by the cyber commandos. Selected from various state police forces, cyber commandos are being trained to confront and neutralise the menace of cyber crime. The first batch is ready and their deployment came recently when the National Testing Agency sought I4C’s help during the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) earlier this year.

Helping youngsters from the threat of cyber fraud or being lured into becoming cyber scamsters themselves is a dual effort by the I4C and state governments. Aiding this effort is the I4C’s ‘suspect registry’, developed with banks and financial intermediaries, to create a national database of cyber criminals posing potential risks. The number currently stands at 80,198 individuals. While legal proceedings will take their course on a case-by-case basis, many are coming forward to confess and share their experiences.

Karri Praveen Kumar from Visakhapatnam is one of the first to share publicly details about the cyber crime racket run by Chinese handlers in Myanmar’s border towns. Lured by a job advertisement on Facebook last November, the engineering student thought it was a legitimate opportunity to support his struggling family. “I had lost my father and we took a Rs60,000 bank loan for my travel,” he said. Praveen flew to Bangkok, where he was kept for three days before being driven to a remote town on the Myanmar border.

“There are thousands of Indians under 30, working for companies running global cyber scams,” he said. “Our job was to create fake Facebook profiles and chat with Indian immigrants in the US, luring them to invest through fraudulent apps. I did not get a single customer in two months, which angered my bosses.” His escape was made possible by a friend in Hyderabad who alerted the state government, which sought I4C’s help.

Now back home, Praveen said he was done with his attempts to go abroad. “I have deleted all the apps. I won’t go on Facebook again. I am planning to pursue an MBA.” His story mirrors that of Mohammed Arbaaz, 26, from Telangana, who left India last December and was rescued in March. “I was just browsing job links on Facebook,” he said. “When I landed in Bangkok, I saw Indians, Ethiopians, Sri Lankans—all working under Chinese bosses for nameless companies creating fake apps and digital identities.”

But there are also several youngsters whose lure for easy money prompted them to take a risk despite warnings from friends and family. Raman Kumar, 27, returned to India in April with help from the Indian embassy in Thailand. The Ludhiana native had a decent job as an accountant in Dubai but things changed when a friend told him about a $12,000-a-month job in Thailand. Though his brother warned it might be fake, he took the risk. From Thailand, he was taken to Myawaddy in Myanmar, close to the border with Thailand, where a Chinese-run company called Hong Shang forced him into romance scams targeting recent Indian immigrants to the US.

Myawaddy, a region controlled by scammers, has two large compounds—KK Farm and Apollo Farm—owned by Chinese nationals. These compounds house multiple scam groups, with electricity and internet facility reportedly supplied from Thailand. “After gaining trust, we would ask them to invest more, promising returns and a personal meeting. Once the money was sent, we blocked them,” he said.

Rahul Pawan, 22, from Punjab, followed a similar path. Coming from a farming family, he left for Thailand in October 2023, spending Rs3.5 lakh to reach Bangkok via Dubai. From there, he was taken to Myanmar. Fluent in English and good with tech, Pawan would chat on dating apps and slowly familiarise the victims with crypto apps. “The company earned $10,000–$12,000 per day,” he said. His office had nearly 80 Indians. Only 25 have returned so far.

The pipeline may still be active but there is light at the end of the tunnel as Amit Shah has pressed agencies to crack down on cyber frauds and trafficking networks luring Indians to Dubai, Bangkok and the border towns in Myanmar and Cambodia. As the crackdown continues, Pawan, now working at a call centre in Mohali, remains cautious. “I am scared of WhatsApp. I don’t trust anyone,” he said. “But I want to warn others: never fall for dating apps or investment offers from strangers.”