FOREVER WAR

It was a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, has been acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated.

These words were written not in 2021, but in 1843. The writer was Rev G.R. Gleig, chronicling Britain’s disastrous, expensive and entirely avoidable entanglement with Afghanistan between 1839 and 1842. The First Anglo-Afghan War was arguably the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the west in the east—only the British mass-surrender to the Japanese in 1942 comes close.

On the infamous Retreat from Kabul, which began on January 6, 1842, only one of the 18,500 who left the British cantonment—assistant surgeon Dr William Brydon—made it through to Jalalabad six days later. Almost all of the Indian sepoys, who made up 90 per cent of the force—mostly Brahmins and Rajputs from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh—were either massacred or enslaved.

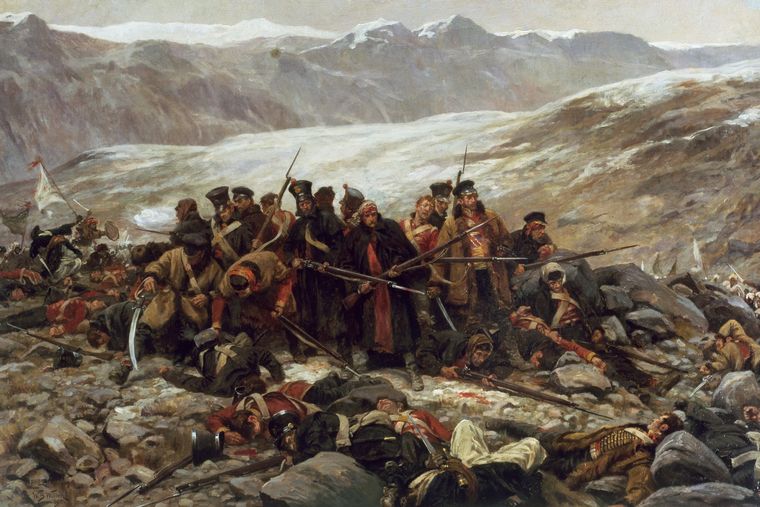

William Barnes Wollen’s celebrated painting of the Last Stand of the 44th Foot—a group of ragged but doggedly determined soldiers on the hilltop of Gandamak standing encircled behind a thin line of bayonets, as the Pashtun tribesmen close in—became one of the era’s most famous images, along with Remnants of an Army, Lady Butler’s oil of the alleged last survivor, Dr Brydon, arriving before the walls of Jalalabad on his collapsing nag. Both images drummed home a terrible truth: an entire army of what was then the most powerful military nation in the world utterly destroyed by poorly-equipped tribesmen.

For many years the mass slaughter of the Retreat from Kabul acted as a deterrent to further western adventures in Afghanistan. As one veteran, George Lawrence, wrote just before Britain blundered into the Second Anglo-Afghan War 30 years later, “a new generation has arisen which, instead of profiting from the solemn lessons of the past, is willing and eager to embroil us in the affairs of that turbulent and unhappy country…. Although military disasters may be avoided, an advance now, however successful in a military point of view, would not fail to turn out to be as politically useless…. The disaster of the Retreat from Kabul should stand forever as a warning to the Statesmen of the future not to repeat the policies that bore such bitter fruit in 1839–42.”

Even as late as October 1963, when Harold Macmillan was handing over the prime ministership to Alec Douglas-Home, he is supposed to have called the younger man to his office and passed on some reassuring advice, “My dear boy,” he said, looking down from his paper, “as long as you don’t invade Afghanistan you’ll be absolutely fine.” Sadly, John Major appears to have neglected to give the same advice to Tony Blair. In 2001, soon after the catastrophe of 9/11, Blair signed up with George W. Bush to invade Afghanistan yet again. What followed was a textbook case of Aldous Huxley’s adage that the only thing you learn from history is that no one learns from history.

For Britain’s fourth Afghan war was to an extraordinary extent a replay of the first. The parallels between the two invasions were not just anecdotal, they were substantive. The same tribal rivalries and the same battles were fought out in the same places 160 years later under the guise of new flags, new ideologies and new political puppeteers. The same cities were garrisoned by troops speaking the same languages, and they were attacked again from the same high passes. In both cases, the invaders thought they could walk in, perform regime change, and be out in a couple of years. In both cases they were unable to prevent themselves getting sucked into a much wider conflict.

The First Afghan War was waged on the basis of doctored intelligence about a virtually non-existent threat: information about a single Russian envoy to Kabul was exaggerated and manipulated by a group of ambitious and ideologically-driven hawks to create a scare—in this case, about a phantom Russian invasion. As John MacNeill, the Russophobe British ambassador wrote from Teheran: “We should declare that he who is not with us is against us... We must secure Afghanistan.” Thus was brought about a disastrous, expensive and entirely avoidable war which had astonishing echoes with our situation today.

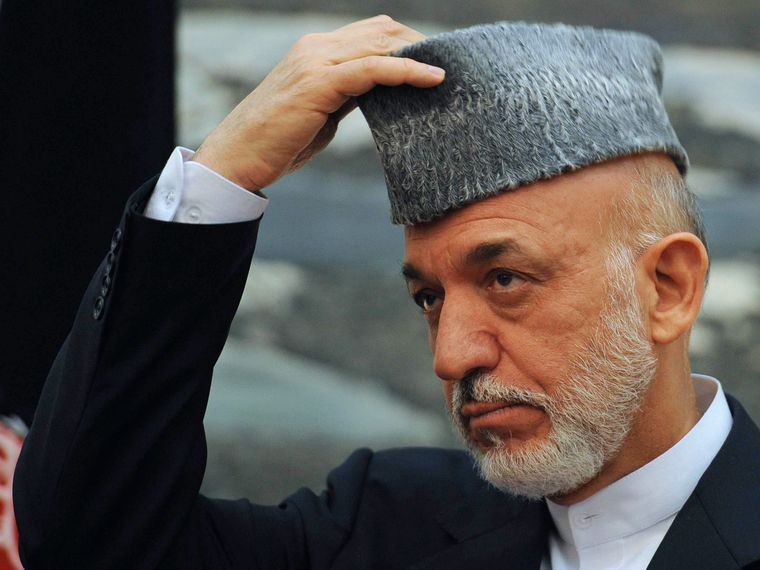

Not only was the puppet ruler the British tried to install in 1839, Shah Shuja ul-Mulk, from the same Popalzai sub-tribe as Hamid Karzai, his principal opponents were Ghilzais, who today make up the bulk of the Taliban’s foot soldiers. Mullah Omar was the chief of the Hotaki Ghilzai, just like Mohammad Shah Khan, the resistance fighter who supervised the slaughter of the British army in 1841.

These parallels are frequently pointed out by the Taliban themselves: “Everyone knows how Karzai was brought to Kabul and how he was seated on the defenceless throne of Shah Shuja,” they announced in a press release soon after he came to power.

The west may have forgotten the details of this history that did so much to mould the Afghans’ hatred of foreign rule, but the Afghans have not. In particular, Shah Shuja remains a symbol of quisling treachery in Afghanistan: in 2001, the Taliban asked their young men, “Do you want to be remembered as a son of Shah Shuja or as a son of Dost Mohammad?”

As he rose to power, Mullah Omar deliberately modelled himself on the deposed emir Dost Mohammad, and like him removed the Holy Cloak of the Prophet Mohammad from its shrine in Kandahar and wrapped himself in it, declaring himself, like his model, Amir al-Muminin, the Leader of the Faithful, a deliberate and direct re-enactment of the events of First Afghan War, whose resonance was immediately understood by all Afghans.

Then as now, the poverty of Afghanistan has meant that it has been impossible to tax the Afghans into financing their own occupation. Instead, the cost of policing such inaccessible territory has exhausted the occupier’s resources. For the last 20 years, the US spent more than $100 billion a year in Afghanistan: it cost more to keep Marine battalions in two districts of Helmand than what the US provided to the entire nation of Egypt in annual military and development assistance. In both wars, the decision to withdraw troops has turned on factors with little relevance to Afghanistan, namely the state of the economy and the vagaries of politics back home.

No one was more aware of these strange parallels than Hamid Karzai himself. When I first published my book on the First Anglo-Afghan war, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, he called me to Kabul, quizzed me on the details over several dinners at his palace about the lessons this history can teach us.

His view was that the US were doing to him what the British had done to Shah Shuja 160 years ago: “The lies Lord Auckland told Dost Mohammad Khan, that we don’t want to interfere with your country, that’s exactly what they tell us today, the Americans and all the others,” he told me. “Our so-called current allies behave [with] us just as the British did [with] Shah Shuja. They have squandered the opportunity given to them by the Afghan people. They tried to do exactly as they did in the 19th century.”

Karzai made it clear that he thought Shah Shuja did not stress his independence enough, and said he was never going to allow himself to be remembered as anyone’s puppet. Having carefully read Return of a King, he substantially altered his policies to make sure he never repeated Shah Shuja’s mistakes. In a leaked email published in The New York Times after Wikileaks, Hillary Clinton blamed his reading of the book for a chilling of relations between Kabul and the White House during the Obama years.

Sadly Karzai’s successor, Ashraf Ghani, learned nothing from the lessons of history, despite being an anthropologist of note. He had none of Karzai’s diplomatic skills and must bear a large share of the responsibility for the collapse of his own regime:

Ghani’s impatience, rudeness and arrogance alienated many tribal leaders and he entirely lacked the charm and politeness that made Karzai a much more popular and acceptable figure. He would tell tribal leaders who had trekked across Afghanistan to see him that they had “10 minutes” and he would take off his shoes, put his feet up on a stool and point them at petitioners—an act of huge rudeness in Afghan as in Indian society. As we have seen, in the end, very few were willing to die to keep Ghani in power.

For the Afghans, the First Afghan War changed their state for ever: on his return in 1842, Emir Dost Mohammad inherited the reforms made by the British and these helped him consolidate an Afghanistan that was much more clearly defined than it was before the war. Indeed, Shuja and most of his contemporaries never used the word ‘Afghanistan’—for him, there was a Kingdom of Kabul, which was the last surviving fragment of the Durrani Empire and which lay on the edge of a geographical space he described as Khurasan. Yet within a generation, the phrase Afghanistan existed widely on maps both in and outside the country and the people within that space were beginning to describe themselves as Afghans.

The return of Shah Shuja and the failed colonial expedition which was mounted to reinstate him finally destroyed the power of the Sadozai dynasty and ended the last memories of the Durrani Empire that they had founded. In this way the war did much to define the modern boundaries of the Afghan state, and consolidated once and for all the idea of a country called Afghanistan.

If the First Afghan War helped consolidate the Afghan State, the question now is whether our current failed western intervention will contribute to its demise. Afghanistan has changed beyond all recognition in the last 20 years. The cities have grown, people travel much more widely, thousands of women have been educated. Television, the internet and an ebullient media have opened many minds.

It is impossible in such circumstances to predict the fate of the divided state of Afghanistan under renewed Taliban rule, even as the resistance begins to organise itself in the Panjshir Valley under the leadership of my old friend Amrullah Saleh, formerly the head of the National Directorate of Security. But what Afghan historian Mirza ‘Ata wrote after 1842 remains equally true today: “It is certainly no easy thing to invade or govern the Kingdom of Khurasan.”

For the truth is that in the last millennia there had been only very brief moments of strong central control when the different Afghan tribes have acknowledged the authority of a single ruler, and still briefer moments of anything approaching a unified political system. Afghanistan has always been less a state than a kaleidoscope of competing tribal principalities governed through maliks or vakils, in each of which allegiance was entirely personal, to be negotiated and won over rather than taken for granted.

The tribes’ traditions have always been egalitarian and independent, and they have only ever submitted to authority on their own terms. Financial rewards might bring about cooperation, but rarely ensured loyalty. The individual Afghan soldier owed his allegiance first to the local chieftain who raised and paid him, not to the shahs or kings or presidents in faraway Kabul.

Yet even the tribal leaders had frequently been unable to guarantee obedience, for tribal authority was itself so elusive. As the saying went: Behind every hillock there sits an emperor—pusht-e-har teppe, yek padishah neshast (or alternatively: Every man is a khan—har saray khan deh). In such a world, the state never had a monopoly on power, but was just one among a number of competing claimants on allegiance. “An Afghan emir sleeps upon an ant heap,” went the proverb.

Also read

- Potential axis of Taliban, China and Pakistan could be a cause for worry for India

- Navtej Sarna: Taliban’s return is the next act of an unending Afghan tragedy

- 'The president fleeing destroyed us': Roya Heydari

- China eyes Afghanistan's trillion-dollar mineral deposits

- Afghan pop star Aryana Sayeed: We’re still in a society of backward-thinking individuals

The first British historian of Afghanistan, Mountstuart Elphinstone, grasped this as he watched Shah Shuja’s rule disintegrate around him. “The internal government of the tribes answers its ends so well,” he wrote, “that the utmost disorders of the royal government never derange its operations, nor disturb the lives of its people.” No wonder that Afghans proudly thought of their mountains as Yaghistan—the Land of Rebellion.

This is now the problem facing the Taliban. As the Taliban transforms its military command into a government for Afghanistan, alliances and tribal configurations that kept two rival Taliban factions together in recent years are already being tested. Factional divisions began to emerge between the Quetta Shura and militant commanders farther east on the ground after the death of Mullah Omar in 2013. The result was a realignment of Taliban factions, particularly between hard-line groups like the Haqqani network that wanted to escalate fighting and more moderate Taliban leaders who sought accommodation with Kabul and Islamabad.

It is too early to see if and how the different Taliban commanders from east and west Afghanistan, the Quetta shura and the Taliban political wing, formerly in Doha, manage to settle their differences and succeed in controlling Afghanistan’s naturally centrifugal polity. Certainly, the recent campaign appears to have had a far more disciplined and coherent coordination than most observers expected. Only time will tell if the movement remains united or splinters into regional Taliban fiefdoms.

Meanwhile, the longer-term strategic picture is grim. Few will now trust American or NATO promises, and we have handed a major propaganda victory to our enemies everywhere. India has lost a leading regional ally and Pakistan’s ISI believe they have won a major victory—Imran Khan went as far as saying that the Taliban victory meant the freeing of the Afghans from the shackles of slavery. Meanwhile, China has announced it will do business with the Taliban regime, and reopen the Mes Aynak copper mine which lies beneath a major Buddhist Silk Road archaeological site.

In 2009, I met some tribal elders from the village of Gandamak, where the British troops made their last stand in 1842. Already then, a decade before this weekend’s debacle, they could see the way the winds were blowing. “All the Americans here know their game is over,” said one elder. “It is just their politicians who deny this.” Said his friend: “These are the last days of the Americans. Next it will be China.”

Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan 1839-42, part three of William Dalrymple’s Company Quartet, is published by Bloomsbury.