On August 5 last year, the Centre cut Jammu and Kashmir in two. It evoked both gasps of horror and raucous applause. However, unlike the svelte assistant in a magician’s saw trick, the state did not come out unscathed. Now sliced into two Union territories, the former state had also lost Articles 370 and 35A, which had given it special status when it joined India. What followed was a tight lockdown, restrictions on movement, a communication blockade and mass arrests.

A year on, the sight of tourists fleeing Kashmir still haunts Feroz Ahmed Shanglu, a houseboat owner near the Dal Lake in Srinagar. “My business was good before Article 370 was revoked,” he said. “The hotels referred tourists to my houseboat for overnight stays.”

The dearth of sightseers dried up his savings; dazed and confused, he approached the Houseboat Owners Welfare Trust for help. The charity, which gives monthly aid to 600 houseboat and shikara owners, took care of him.

Later in the year, after the lockdown was eased a bit, Shanglu met owners of several hotels and guest houses, looking for work. “They used to hire me for making kahwa and noon chai (salt tea) for tourists, but none of them had any business,” he said. Since June, he has found some work at weddings and small events outside Srinagar. “I get Rs 700 a day (selling tea), but save only Rs 500 because I have to pay for travel,” he said. As fewer weddings are taking place, Shanglu has not been able to provide for his family, which includes his wife, two children and his old mother. “Without help from the charity, my family would starve,” he said.

Abdul Khaliq Shora, another houseboat owner, said, “I am 70. I cannot go out looking for work. I survive on aid from the charity.” Shora, who lives with his wife, divorced daughter and grandchild, said his houseboat had been lying vacant since August and needed repair.

Tariq Paltoo, who owns two houseboats and a guest house, and works as a volunteer for the charity, said, “Our charity is supported by our community members outside Kashmir. Our community is not used to aid and that is why every family listed with us is identified by a code number and food kits are delivered to them at night.”

Land rides have fared no better. Ghulam Nabi Pandav, chairman, Kashmir Tourist Taxi Operators Association, said 26,000 cab drivers were without work since August. “Many drivers are working as labourers away from their homes so that nobody recognises them,” he said. “We were told rivers of milk would flow in Kashmir after Article 370 [was revoked]. Where are those rivers?”

The carpet industry, one of the mainstays of business in Kashmir, is also hanging by a thread. At Pattan and Sumbal, considered the carpet belt of Kashmir, dozens of weavers have closed their looms and have taken to menial labour. “There was no raw material as everything was shut and phones were also blocked,” said Nazir Ahmed Malik, a weaver in Pattan. A half-finished carpet lay unattended as he spoke. “Even if I had completed this carpet, there would be no buyers,” he said. “My son now works as a labourer in Srinagar and that is all we are surviving on.”

The story repeats itself in neighbouring villages.

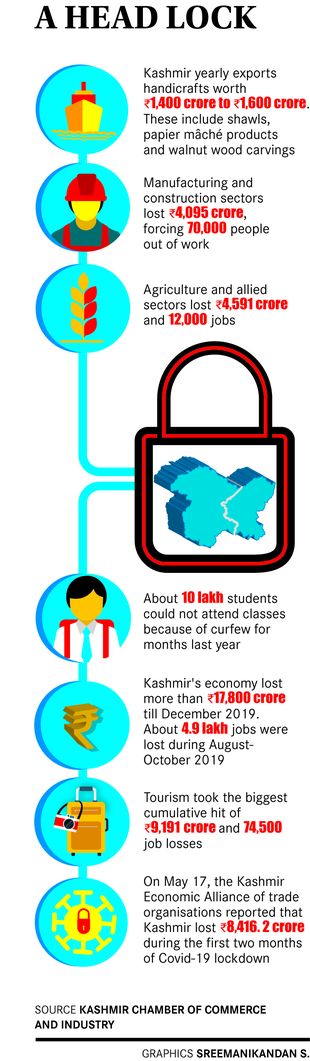

Every year, Kashmir exports about Rs 1,600 crore worth of handicrafts, which includes shawls, papier-mâché products and wood carvings. Parvez Ahmad Bhat, president of the Artisan Rehabilitation Forum, said there were more than the “official” 2.5 lakh artisans in Kashmir, and that the handicrafts department seemed unmoved by their plight.

Syed Kounsar Shah, who exports papier-mâché products, said some artisans had become suicidal because of unsold stocks. “We are now arranging counselling [sessions] for them,” Shah said. “I am an award-winning exporter, but today, like most artisans, I feel desperate.”

The lockdown aside, the suspension of high-speed internet also killed many businesses. Hundreds of WhatsApp accounts, which could not be updated, were deleted. “We used to get orders online and the money through net banking,” said a female entrepreneur. “But after the internet was blocked, we could not do any business.”

Education also stalled. About 10 lakh students could not attend school and college for months last year because of curfew-like restrictions. They returned to classes in March, but the pandemic forced them back home. And though online classes have been introduced, the slow internet has played spoilsport.

The story in Kashmir’s apple orchards, too, is not rosy. In October, after militant attacks on apple traders and on truck drivers coming into Kashmir discouraged them from pursuing deals, local farmers were left without buyers. The government offered to buy the fruit, but not many growers came forward.

As the autumn leaves fell, sector after sector bled. As per a December report of the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kashmir lost between Rs 14,296.10 crore and Rs 17,800 crore, and 4.9 lakh jobs between August and December. In July 2020, it updated the figure to Rs 40,000 crore.

In Jammu, however, most of the restrictions of the post-abrogation lockdown were quickly lifted and internet connectivity was restored earlier. The region saw growth in manufacturing of plastic and steel products, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, and animal and poultry feed. The toll on imports from other states was also abolished, making goods cheaper for consumers.

Local businesses, however, are worried about their ability to compete with cheaper goods from outside. “Our cost of manufacturing is higher than neighbouring states because we import raw material from outside,” said Annil Suri, former president of the Bari Brahmana Industries Association. “We have to pay higher freight charges on raw material; skilled manpower also comes from outside.” He said that, after they paid migrant workers in March, all of them were ferried out. “Now there is labour shortage in Jammu,” he added.

For most people in Kashmir, the revocation of articles 370 and 35A was always about changing the demography of India's only Muslim-majority state. This impression only deepened after the Centre, on March 31, announced new domicile rules under the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Adaptation of State Laws) Order, 2020.

The order defined domiciles as those who have lived in Jammu and Kashmir for 15 years and those who have studied for seven years and appeared in Class 10 and Class 12 exams in schools there. It also included any Indian citizen who had been an employee of the Central government or a public-sector undertaking in Jammu and Kashmir for 10 years. And, the children of anyone who fulfilled the criteria above.

Until last August, only permanent residents were considered domiciles. Article 35A defined a permanent resident as a person who was living in Jammu and Kashmir on May 14, 1954, or had been living there for 10 years and had lawfully acquired immovable property. The state government would issue them a Permanent Resident Certificate (PRC), which was needed to apply for government jobs and to buy immovable property.

Then, on May 18, the UT administration issued the Jammu and Kashmir Grant of Domicile Certificate (Procedure) Rules, 2020. Under these, the tehsildar has to issue the domicile certificate within 15 days of application, failing which he could lose Rs 50,000 from his salary.

“This is unprecedented,” said a tehsildar who did not want to be named. “While issuing PRCs, it used to take weeks and sometimes months to verify the antecedents of the applicant.” Another tehsildar spoke of a recent procedural headache. After she had sought documents from a man who claimed to be living in Kashmir for more than 15 years, she got a call from an Army officer asking her to issue the certificate. “I told him that the man had no documentary proof or witnesses to support his claim,” she said. “I told him he would be posted elsewhere tomorrow, but I have to live here and cannot flout the rules.” She said the officer understood and did not insist.

While the government has said that permanent residents will get the domicile certificate based on their PRCs, the order has sparked fears of a National Register of Citizens in Kashmir. In fact, some revenue officials THE WEEK spoke to in Kashmir believed that it was easier for an outsider to get the domicile certificate. The rules dictate that the PRC should match with government records, but the officials feared that some records could have been lost due to a number of reasons, including floods and fires.

The immediate beneficiaries of the domicile law are the migrants living in Jammu and Kashmir. Currently, at least 17 lakh of them are eligible for a domicile certificate.

Also, with a nudge from the Centre, the underprivileged from other states could look to Jammu and Kashmir for a better life. That will not only alter the demography of the Union territory, but also reduce the societal clout of permanent residents.

It could also affect jobs. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, the unemployment rate in Jammu and Kashmir is currently 17.9 per cent, far higher than the national average of 8 per cent. The domicile law has come at a time when, according to the Union home ministry, there are 84,000 government vacancies to be filled.

Also read

- Ladakh statehood protest: Apex body leaders signal readiness for talks amidst unrest

- J&K assembly passes Article 370 resolution amid protests

- Supreme Court to consider plea for time-bound restoration of statehood to J&K

- Article 370: Tight security in J&K; regional parties await SC verdict

- SC verdict on Article 370 today. Here is the recap of the hearing

- SC to hear pleas challenging abrogation of Article 370 from August 2

As for investment from outside, sources said the revenue department had identified around 50,000 acres, mostly in Jammu, to set up industrial units. According to sources in the State Industrial Development Corporation, several companies have shown interest in investing in a variety of sectors, including health care, hospitality, education and agriculture.

Chaitanya Sharma, manager of the Jammu and Kashmir Trade Promotion Organisation, told THE WEEK that they were in talks with companies, but the pandemic had put everything on hold.

Some local businessmen said they welcomed outside investment, but that the government should dispel fears that inviting such companies was not part of the plan to change the region’s demography. “Land could be leased to outsiders to set up business even when Article 370 was in effect,” said a businessman. He added that the government had also, on July 18, approved amendments to the law to allow marking of “strategic areas”, where the Army could carry out unhindered construction and related activities.

Syed Mujtaba, a lawyer in Kashmir, said the Centre could not make any law as the abrogation had been challenged in the Supreme Court. “The lieutenant governor does not represent the people of Jammu and Kashmir, but the Centre,” he said. “The people have no agency.” A government spokesman, however, said there were adequate safeguards in place and accused the political parties of spreading misinformation.

Unlike in Kashmir, the scrapping of the state's special status was greeted with cheer in Jammu, especially by BJP supporters. The domicile law, however, has them worried about losing jobs and business to outsiders. There has been no open dissent in Jammu for fear of strengthening what they consider “anti-national” protests in Kashmir.

Zorawar Singh Jamwal of Team Jammu, a socio-cultural group, said that though he was concerned, the new domicile law did have safeguards. “Navin Choudhary (an IAS officer from Bihar whose domicile certificate went viral) has been living in Jammu and Kashmir for 26 years,” he said. “Only then has he gotten the certificate.”

However, Sushma Singh, who lives on the outskirts of Jammu, said she was worried about the future of her daughter, who recently passed her CBSE class 12 exams. “Now outsiders will also stake a claim on seats in professional colleges here,” she said. “We are now feeling insecure.”

Harsh Dev Singh, chairperson of the Jammu-based National Panthers Party, said the domicile law was unfair to the educated youth of Jammu and Kashmir, and that the government should at least have retained the permanent resident status. “There has been no development and only retrenchment since last August; around 1,200 health workers were sacked,” he said. “Employees of the information and education departments have also been removed. No daily wager has been regularised.”

That all is not well for the BJP in Jammu was evident when the party won only 52 of 148 seats in the block development council elections in October. This when the National Conference and the Peoples Democratic Party did not contest.

Notably, most political leaders detained in early August have been reluctant to broach the topic of abrogation even after their release several months later. The silence of the senior NC leaders and former chief ministers Farooq Abdullah and his son, Omar, has fuelled speculation that the party is hoping only for the restoration of statehood. On July 27, Omar wrote in a national daily that he would not contest assembly elections as long as Jammu and Kashmir remained a Union territory.

The party's workers, some of whom have spent their whole lives with the NC, are not pleased. “We fought separatists only because we had autonomy, our own flag and laws that protected our identity,” said a leader in Srinagar. “Now we have nothing and our party is saying it will fight in court.”

The reason the burden of fighting is on the NC is that it is the only party whose leadership and support base are still largely intact. And the BJP knows this. The party is now banking on the delimitation process, which would be completed in May. As part of this, Jammu is expected to gain twice the number of seats as Kashmir. Before last August, the state assembly had 87 seats, including four from Ladakh. Kashmir had 46, Jammu 37.

The BJP hopes for votes of the West Pakistan refugees, Gorkhas and Valmikis, who have gained certain rights because of the abrogation. The party is also banking on the new domiciles, especially in the Muslim-majority areas of the Chenab valley and the Pir Panjal region of Jammu.

Only Mehbooba Mufti, PDP president and former chief minister, who is still detained under the Public Safety Act at her home in Srinagar, continues to be defiant. Analysts said she wants to salvage her image, which was sullied by her alliance with the BJP in 2014. The party, though, seems to be in disarray as many of its leaders have joined the Jammu and Kashmir Apni Party, which PDP minister Altaf Bukhari floated with the BJP's backing last year.

As for the separatists, the abrogation has left them in tatters. On June 29, Syed Ali Shah Geelani resigned from the chairmanship of the Hurriyat Conference (G) and accused its constituents of shying away from accountability.

The separatists had lost traction long before August 5 because of internal feuds and the inability to get public support. The Centre's crackdown on separatists through the National Investigation Agency hit both factions of the Hurriyat Conference, headed by Geelani and Mirwaiz Umar Farooq.

As expected, the abrogation has affected the security of the region. Since January, security forces have killed at least 133 militants in Pulwama, Shopian, Kulgam and Anantnag districts of south Kashmir. After last August, the state police came under direct control of the Centre. That freed it from political interference and increased synergy with the Army and the CRPF.

In 2019, security forces had killed 133 militants before August 5, and only 25 in the remaining months. “We resumed operations after two weeks [of the abrogation],” said a senior police officer. “The priority was to prevent 2010- and 2016-like agitations in which many civilians were killed.”

The restraint, however, led to several militants infiltrating from Pakistan. Minister of State for Home G. Kishan Reddy, last December, told Parliament that there were 84 infiltration attempts and 59 militants could have slipped in.

Last October, a new militant group, The Resistance Front (TRF), announced its presence with a grenade attack on security forces at Hari Singh High Street in Srinagar; seven people were injured. That the group had been active on Telegram while internet was suspended in Kashmir led to suggestions that its handlers were in Pakistan. The police said that Pakistan had formed the TRF to mislead the Financial Action Task Force, which had threatened to blacklist the country for supporting terrorism. “Lashkar floated the TRF with some members of the Hizbul Mujahideen,” said Vijay Kumar, inspector general, Jammu and Kashmir Police.

The group gained notoriety after five of its militants and five Army men were killed in an encounter on April 4 near the Line of Control in Kupwara. After that, security forces intensified operations.

In April, 23 militants were killed in the first 24 days. But, on May 3 and 5, eight security forces personnel and two militants were killed in two engagements with the TRF at Handwara in Kupwara.

On May 6, the security forces killed Riyaz Naikoo, Hizbul Mujahideen chief operations commander, and his associate at Beighpora in Pulwama. “While on his trail, we managed to bust six of his hideouts,” said Kumar. “We interrogated some of his over-ground workers and got vital information.”

On May 19, Junaid Sehrai, the Hizbul Mujahideen’s divisional commander for central Kashmir, and his associate Tariq Ahmed of Pulwama, were killed in Srinagar. “In the past two months, there have been attempts by the JeM (Jaish-e-Mohammed) to carry out a Pulwama-type attack, but we have foiled them,” said a senior police officer. Security forces are on the trail of other listed militants, including Naikoo’s successor Saifullah Mir alias Ghazi Haider and JeM IED expert Adnan Bhai.

There have been political casualties, too. On July 8, militants shot dead BJP state executive member Sheikh Waseem Bari, his father Sheikh Bashir Ahmad and brother Sheikh Umar, who were also office-bearers of the party, outside their Bandipora home. The attack happened a month after Ajay Pandita, a Congress sarpanch, was shot dead by militants in his village of Larkipora in Anantnag. Deputy General of Police Dilbag Singh said the attack was the handiwork of a hybrid group of local and foreign militants working together to confuse security forces.

In another significant move, security forces have stopped handing over the bodies of local militants to their families to prevent emotional funerals, which they said motivated the youth to join militancy. Though police have cited the pandemic as the official reason, police sources said the policy was first discussed in 2018, but could not be implemented due to objections by local politicians.

Kashmir has seen many such changes in the past one year. And now, another autumn beckons. The chinar leaves must fall again; hope, though, can cling on.