Lee Kuan Yew ran Singapore like a corporation. When the prime minister stepped down in 1990, the mosquito-infested marshy piece of land he got 25 years earlier from the British had become a gleaming city with a thriving port. With the meagre means his country had to offer, he could have done it in only one way—foreign investment. Lee ardently wooed it, and he tolerated nothing that hampered economic progress.

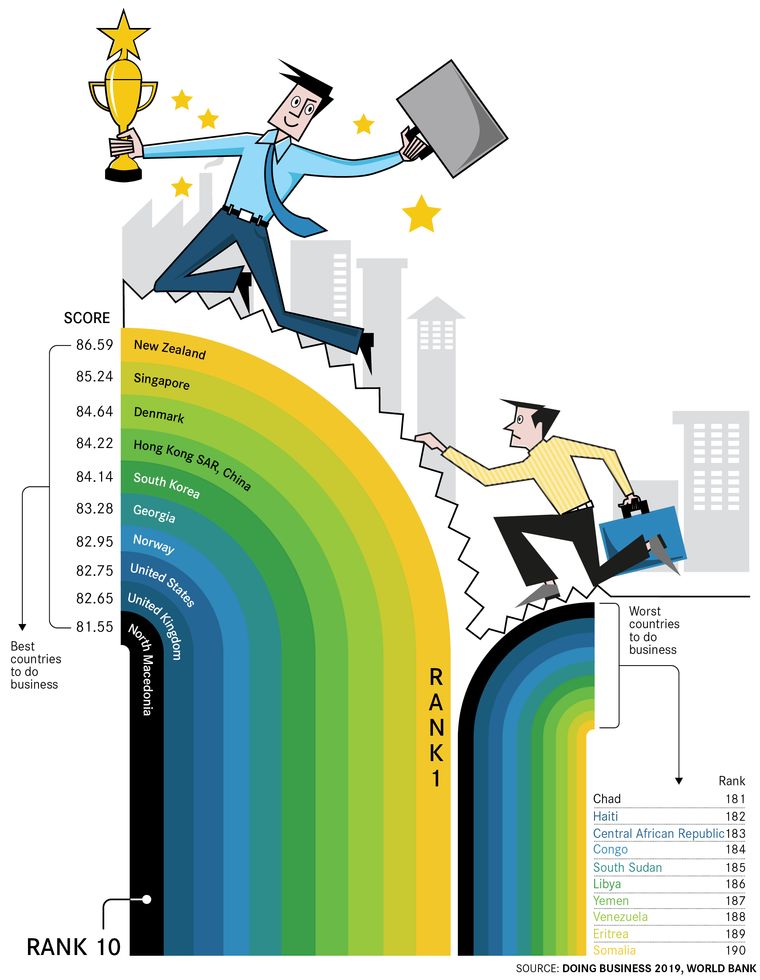

Singapore tripled its per capita income in nine years after independence. Currently, its per capita gross domestic product is among the top three in the world, just behind the oil-rich Qatar and the high-income Luxembourg. And it topped the World Bank’s Doing Business Index rankings ten times since 2004, when the annual ranking started.

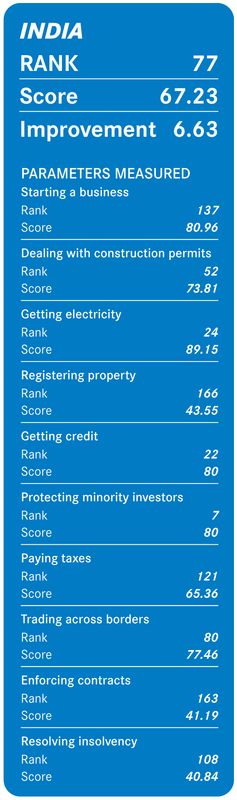

Strictly speaking, there is no close relationship between ease of doing business and economic prosperity. In fact, in a liberal economy, further deregulation can lead to cronyism. But in India, which had long been a state-regulated economy, businesses doing well can be good for everyone. In the latest ease of doing business ranking, India is in the 77th spot, behind countries like Mongolia and Peru. That is a shame for an economy which aspires to touch the $5-trillion mark in 2024.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has reduced the time needed to register a new business to 30 days. But it is just six days in the US. A year ago, Modi even launched an ‘Ease of Doing Business Grand Challenge’ and said India was just a few steps away from breaking into the top 50. That was a noble intention. India’s per capita GDP, which is an indicator of affluence, is lower than that of Iraq, Namibia and Bhutan. It is just half of Sri Lanka’s and about a quarter of China’s. To fill this gap India needs to grow really fast.

If India grows at a rate of around 7 per cent a year, it will take more than two decades to reach China’s current per capita GDP. If it is to become a $5 trillion economy by 2024, it has to grow at around 8 per cent. If it achieves that, the per capita GDP may double from the current figures.

That kind of growth will not come with the current bottlenecks. The latest Indian budget seeks to attract big foreign investment without doing enough to make the economy attractive. Several of India’s neighbouring countries, for instance, have corporate tax rates of 15-20 per cent. In India, it is 25-30 per cent. India has higher rates than many Asian countries for electricity, air freight and income tax as well.

Investors consider all these, not just the business prospects, before investing their money. They balk at tax terrorism and despise bottlenecks. And the huge business opportunities that India’s enormous middle class offers may not be good enough to compensate for an unfavourable business environment.