It is a humid afternoon in the iconic red brick campus of IIM Ahmedabad. I am told that most students who are free from classes are busy with their work—reading case studies, preparing for surprise quizzes or completing assignments. Even the few lucky ones who can afford to ‘lounge’ in the cafeteria do not seem relaxed; it is only a short break from their punishing schedules. Two students from overseas are sitting opposite the cafeteria, smoking cigarettes. Behind them, across a green lawn, is the magnificent Louis Kahn Plaza, the open auditorium where the graduation ceremony takes place.

Saurabh Chandra stands out in the crowd because of his relatively formal clothes (jeans, shirt tucked in and a black blazer). He is also calm and collected. Chandra, currently an engineering leader at Amazon, has 17 years of work experience, in the US, Europe, Brazil, China, Israel and India, at various Fortune 500 companies and unicorns (privately held startups valued over $1 billion). He has authored two technology books and holds three patents. Looking at his CV, one could be forgiven for assuming that he was here to give a talk. But Chandra is a student at the institute’s new ePost Graduate Programme (PGP).

“The whole dimension of business changes every five years,” says the 36-year-old. “If you are not in touch, you are lagging behind. There were two options. One, take a break and scan all the industries. Or, come to a place where all these things come under one roof.” Chandra says the learnability goes up ten times at IIMA because the professors are world class and the students high quality.

IIMA started the online version of its flagship two-year programme in 2017. There are 85 classrooms spread across 50 cities and towns. It is exclusively for working professionals and entrepreneurs, and the applicant must have at least three years of full-time work experience (after graduation) and must be 24 years or older. Chandra’s batch (2017-2019), the first in the programme, has 52 students, whereas 64 applicants made the cut for the second batch.

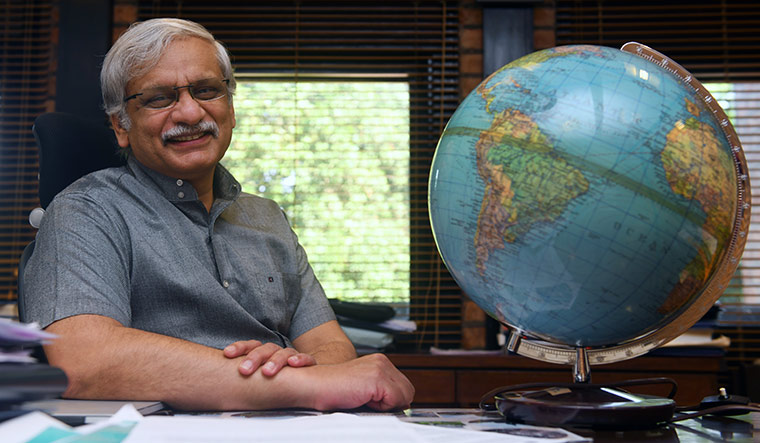

“Many people who would have liked to come to our programme may have been forced by circumstances to go to work,” says Professor Errol D’Souza, director of IIMA. “Later, they find it difficult to give it up because they are supporting a family. So this is a way for them to benefit from our expertise. Plus, it is our way to reach out. In ePGP we are teaching students in tier II and tier III cities, thereby impacting the economy much more.” He adds that as technology improves, ePGP would become more prevalent.

But, why is it offered only to applicants with experience? “Management as a discipline thrives if your students are experienced,” says D’Souza, who has been with IIMA since 2001. “When you are discussing a problem in the class, they can immediately relate to something they have lived through.” E-learning, he says, is more difficult when you do not have experience. “Here, we can teach freshers because the pedagogy allows us to bring cases which are live about the type of problems that organisations face,” says D’Souza. The pedagogy of case method, he says, is about learning through each other’s experiences. “The technology does not allow multiple people to speak to each other from different locations,” adds Prof D’Souza. “Recognising this limitation, we have kept it for people with experience.”

Would he then recommend that, in the future, b-schools accept only students who have work experience. “It will happen over time,” says D’Souza. “Whether we want it or not, at some stage corporates will reach out much more to students at their undergrad colleges.”

Chandra says ePGP is the best choice if you are in an organisation and already creating value. “But if you have just started and you feel that nothing great is happening, you may want to go back and learn. Then PGP works. So, both have strong differentiators,” he says. It is important for students opting for ePGP to understand what they are getting into. “The first three months will be a shock,” says Chandra. “Because you have to juggle your work life and the rigorous course. We have to make six to seven hours a day for studies, apart from about eight hours of work.” The programme fee is around Rs17 lakh and, according to Chandra, the travel and other expenses are around 10 per cent of the fee.

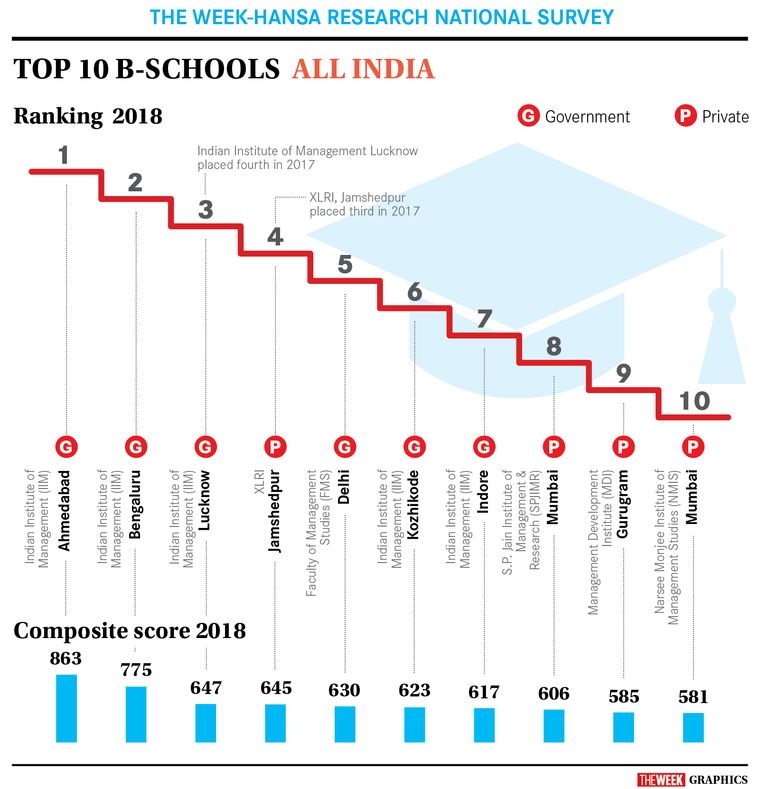

While the future may well be virtual, IIMA’s PGP is going strong and continues to be one of the most coveted programmes in the world. IIMA is ranked first in THE WEEK-Hansa Research Best B-Schools Survey this year, followed by IIM Bangalore. (For other top-ranked institutes, see story starting on page number 96.) In the 2018-2020 PGP batch at IIMA, out of 1,87,683 aspirants who applied for the programme, 399, or 0.21 per cent, were admitted. The minimum CAT percentile for the students who joined was 89.22 (general category). This is a sharp decline from the 2015-2017 batch when it was 97.97. But this might be because of the fact that CAT is a relative exam.

IIMA and IIMB along with IIM Calcutta—the ABC of management education in India—were the only three Indian institutes in the Financial Times Masters in Management rankings 2018 (19th, 23rd and 26th, respectively). IIMC is not in our list because it opted out and preferred not to be named (see methodology).

IIMA was ranked first in four criteria—’salary today’, ‘weightage salary’, ‘employed at three months’ and ‘faculty with doctorates’.

D’Souza says that IIMA usually calls the top 1,500 from CAT for personal interviews. But the candidates’ past achievements are also given a certain weightage. “We look at the percentage obtained in the tenth, twelfth and bachelor degree, and convert that into an application rating. Or whether you are in the top 5 per cent in your discipline. So it is possible that someone who was 3,000 in CAT could be called for the interview,” says D’Souza.

The first year of PGP is a core course, which all students have to take. It covers the basic subdisciplines of management. There are also a set of courses to round off these basic courses, such as communication and ethics. In the second year, after summer internships, students are given electives. In a given year, IIMA offers around 130 electives, the largest number available in India, according to D’Souza. The students are supposed to choose 18.

The institute does not offer specialisations. D’Souza says this is because it is a pre-experience course. “There are some students who come in with work experience,” he says. “But by and large it is a course for students who have not worked in the real world. So, it does not make sense to say that I am going to get you specialised in a particular area. We prefer that the students are given a broad foundation.”

For specialisations, he says, students can come in for executive education programmes. “We believe that it is a lifelong learning process,” he says.

A crucial aspect of the PGP is the summer internship after the first year. With the kind of internships that IIMA gets for its students, this is no cakewalk. Vikas Chauhan, 22, from Chandigarh, who had not travelled by air till he joined IIMA, went to Cebu in the Philippines for his internship. “For namesake, it was a consulting firm,” says Chauhan. “But, I did HR work, I did operations work, I did finance work, I went on field visits because it was an infrastructure project in one of the biggest international airports in the Philippines. It was an amazing experience.”

Chauhan says that his internship was so strenuous that he used to leave for work at 7am and return at 1am the next morning. “And I did that for 56 days straight,” he says. “We were working on a deadline. My internship ended on May 31 and the inauguration for that segment of the airport was on June 5, and that was to be done by the president of the Philippines.” Chauhan wants the same thing for his career. “The job should be strenous enough,” he says. “I am happy to do a 14- to 16-hours-a-day job and still be paid less than a nine-to-five job. But, the work should be enriching. That is where I will be able to test my skills.”

The pressure the students are under is mind-boggling. “Classes are one thing you cannot miss,” says Chauhan. “Academics are one thing you cannot ignore. And quizzes are one thing that will make your life hell.” Right from day one, the students are kept busy with classes day in, day out (an average of 13 courses a term in the first year against eight to ten in other b-schools), pop quizzes, assignments, projects, field trips and group activities. The grading gives weightage for all of the above, and for class participation and the exams. But the fact remains that those who make the cut are more than equipped to handle it. “I knew it was going to be a pressure cooker,” says Sandeep Ramachandran, 23, from Chennai. “I was mentally and physically prepared for it. I have friends who have passed out of here and they had prepared me for this. They had told me that first year was going to be really tough, especially the first couple of terms.”

For parents who may complain about the pressure the students have to face, the director’s message is clear. “Once they have entered here, be very clear that your children are going to be treated like adults,” says D’Souza. “They are going to be forced to make decisions. They will be pushed a lot. Much more than they actually would have thought they are capable of. It is a tough life. Many of our students crib that they are sleeping four to five hours a day.”

IIMA is not allowed to accept students from overseas in a way it would deny opportunity to Indians. However, 10 per cent extra seats are reserved for foreigners. It also has foreign exchange programmes. Having students from abroad as part of study groups is an advantage for Indian students. Sreenidhi S., 21, from Chennai gives an example of how they help broaden the perspective of the Indian students. “Once when we were discussing a case study about McDonald’s, a French student who was in our study group told us how the company had gone into healthy food in France,” she says. “It helped us appreciate how MNCs change their offerings based on consumer preferences.” The French student, Mathis Degroote, 22, from EDHEC Business School, Lille, says that the classes at IIMA were more of an exchange between the teacher and student. “We have a scholastic method of learning based on lectures and theory,” he says. “Here, they discuss more and it is based on case studies. It is something we don’t have in France.”

The institute has been committed to the agri-business sector since its inception in 1961. A special programme in agriculture was started in 1974. This has today evolved into the PGP in Food and Agri-Business Management (PGP-FABM), which has been consistently ranked first in the world by Eduniversal, Paris. Umang Agarwal, 31, from Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, has a PhD in animal sciences from the University of Maryland, US. He joined PGP-FABM in 2017 and sees it as an opportunity to change gears and get into the business of food and agriculture. “It is a meticulously designed course,” says Agarwal. “They take you on a ride in the whole first year. Finance, marketing, HR, all these verticals of business administration are taught to you in small packets. Courses keep changing. There are moments you don’t realise what is happening. But when you come out of the first year, it would have changed you. It is an enlightening experience.”

The institute also offers a one-year programme for executives, the PGPX, started in 2006. It has been ranked 31st in the world by Financial Times in 2018. It was ranked second in ‘career progress’. Since the focus is on preparing for top management, the programme only accepts candidates with at least four years of full-time work experience after graduation and 25 years of age. The current batch has an average GMAT score of 700 and work experience of 8.5 years. (GMAT scores range from 200 to 800.) After a rigorous grounding in the fundamentals of management and a segment to prepare them for “visionary leadership”, the students are sent for International Immersion Programmes (IIPs). This is a two-week stint at an international university, which allows students to understand the economic environment in a foreign country. Neha Arora, 30, a former Infosys employee, has just returned from her IIP at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She says that the rigour at the Chinese institute pales in comparison to what they are used to at IIMA. “We are used to working, discussing case studies, till 3am or 4am, and we have classes at 8am again,” says Arora. “There, we didn’t have to study that much.”

IIMA offers more than 100 short-run courses. Popular programmes other than the PGPs include a fellowship in management, a faculty development programme to help faculty of other b-schools imbibe the methods at IIMA, and a six-month programme for armed forces veterans, where they are trained for another life in the corporate sector.

The course fee for applications under domestic category for the PGP and PGP-FABM is around Rs22 lakh. For PGPX, it is around Rs27 lakh plus the cost of IIP. D’Souza says that the scholarship structure ensures that no deserving student misses out because of financial constraints. “It is a graded scholarship scheme,” he says. “So someone who comes from a family with income less than a certain amount, say Rs6 lakh annually, is given a full scholarship, Rs6 to Rs12 lakh is given 80 per cent.” The reason the institute does it that way, says Prof D’Souza, is because it believes that the strength of the education will get the students a job that will pay it back. “You should actually work towards earning the returns from your education. Most of our students get back their money within the first one and a half years of their work life. It is hard to think of a business which has that sort of a payback period,” he says.

In fact, the placement data speaks for itself. In 2018, for the 372 students who accepted domestic offers, the average salary (total earning potential) was about Rs24.5 lakh a year. The lowest was Rs13.7 lakh and the highest Rs72 lakh. For the 16 students who accepted international offers, the average total earning potential was about $73,000 (about Rs53 lakh)—the lowest was $38,274 (about Rs28 lakh) and the highest $99,172 (about Rs73 lakh). Professor Amit Karna, 41, professor in strategy and chairperson of placements for IIMA, says that recruitment decisions should not be driven solely by salary. The focus, he says, should be towards making a career choice, rather than maximum salary of the job offered. “We focus on getting the right fit between recruiter and student. This has led to a consistent increase in attracting better opportunities for our students and better employees for our recruiters” says Karna.

The institute did away with the day-based system of placements eight years ago. This involved companies offering the highest pay coming for recruitment on the first day of placements. Karna says this put unnecessary pressure on students and that was why IIMA switched to a cluster system. “Companies offering similar profiles are grouped together and invited to campus as a cohort, and several cohorts form a cluster” says Karna. “Recruiters are classified based on the sectors they belong to and roles they offer rather than the salary they offer. This helps students to make decisions in a more comfortable way.”

At IIMA, students can make “dream” applications to a firm even with an offer in hand. Moreover, pre-placement offers (PPOs) that students may receive from their summer internships are not binding. Students can hold these offers and continue to try for jobs with firms coming to later clusters if they prefer those firms. However, if students get offers from their dream company, they have to accept it. “This gives students the flexibility and choice to build careers in sectors that fit with their aspirations,” says Karna. “Recruiters also benefit greatly because they are hiring someone who makes a choice after looking at all possible options.”

Another prominent feature of placements at IIMA is the “Placement Holiday Programme”. Students are allowed a two-year leave to try out their ventures under the programme. It works as a safety net in case they want to return and sit for placements. Wouldn’t that be unfair to the next batch who have to face competition from these returning seniors? “Majority do not exercise this option as their ventures flourish,” says Karna. “Usually five to ten students take placement holiday.” He adds that students do not find it unfair because the numbers are low and all of them get the same option.

The alumni have an important role in the placements. They not only act as brand ambassadors, but also share the latest trends and their own achievements with the students, which teach the students a great deal about the industry. This fits in with the motto of IIMA: Vidyaviniyogadvikasah (development through the distribution or application of knowledge).

IIMA makes students involved in all aspects through about 40 clubs and committees—from the placement committee to the media cell, and sports and cultural activities. I am sceptical about how the students find time for sports and cultural activities till I run into Umang Agarwal, again, near the famous window on the outer wall of IIMA’s old campus. (Outside the window sits Rambhai Kori, 60, a street vendor who sells tea, snacks and cigarettes. He was the subject of an IIMA case study on entrepreneurship ten years ago.) Agarwal, who was a member of the music club last year, tells me that he can arrange a jamming session if I am interested to see the music club in action. And so we head to the Harvard Steps, a tribute to the American business school which helped set up IIMA.

As members of the music club sing their hearts out on the front steps of the institute, D’Souza passes by discreetly. He is least bothered by the racket. Perhaps because he has more important things on his mind. “As per the IIM Act, the government was supposed to formulate a set of rules to determine its interaction with the institute,” he tells me. “They were supposed to do it by January end, but we are still waiting as of September end.” The act says that the pay scales of the faculty will be determined as per the government of India. D’Souza tells me it is difficult to retain the faculty because of the opportunities they have abroad. “We were hoping that the government does not put a restriction on us in terms of the salaries being linked to the bureaucracy,” he says. “That is the real constraint.”

If the government really wants IIMA to spread wings, it should give it the freedom to operate globally, says D’Souza. “We are very clear that we have a mandate to serve India,” he says. “That we know. But we also believe that India is best served if we are global. We were hoping and we still hope the government gives us that freedom to operate.”