T.N. Raghunatha, the secretary of a large housing society in Thane near Mumbai, is a relieved man now. The society’s bank account was in the New India Cooperative Bank. In February, the Reserve Bank of India superseded the board of the urban cooperative bank (UCB) and established a withdrawal limit of Rs25,000.

With the bank now being acquired by rival Saraswat Cooperative Bank, the freeze has been lifted. The depositors can now access their deposits, including term deposits.

“From day one, Saraswat bank has given access to funds,” said Raghunatha. “There have been no haircuts, no loss of depositors’ money.”

The reason behind New India bank’s troubles was alleged mismanagement. The Mumbai Police has registered a case against the former general manager of the bank for allegedly siphoning off Rs122 crore. Its economic offences wing (EOW) is probing the case and has filed a charge-sheet. The UCB’s former chairman Hiren Bhanu, his wife Gauri Bhanu, and another former chairman, Satish Chander, are among those named.

Among various allegations, the EOW has alleged that the bank sanctioned loans to the tune of Rs77 crore to a company without due diligence. The loan accounts were later declared as non-performing assets.

For depositors, the withdrawal limit enforced by the RBI was a problem. Raghunatha’s society had significant deposits in the bank. Luckily for him, his society had moved its maintenance account to Saraswat bank more than a year ago.

Saraswat is India’s largest urban cooperative bank with a total business of Rs91,814 crore, as of March 31, 2025. The bank’s chairman, Gautam Thakur, is confident it will cross Rs1 lakh crore in the current financial year.

“We are the largest in the [urban] cooperative banking space and it is incumbent upon us as the leader to step up whenever we feel it is necessary,” said Thakur. “We took interest as there are many synergies we see with New India bank.”

The crisis at New India bank has got to a favourable resolution for the depositors, but, not all cases have such happy endings.

Since 2020, the RBI has cancelled the licences of 58 UCBs. Between 2014-2024, this number stood at 78. Notably, examples from recent years include the 110-year-old Rupee Cooperative Bank in Pune—its licence was cancelled in 2022 because it did not have adequate capital and earnings prospects. Vijayawada-based Durga Urban Cooperative Bank was shuttered in November 2024 after bad loans and unpaid interest reportedly rose to Rs200 crore—the RBI stated that, in its financial position, it would be unable to pay depositors in full. In April, Ajantha Urban Cooperative Bank, Aurangabad, and Imperial Urban Cooperative Bank, Jalandhar, suffered the same fate. In May, the RBI imposed restrictions on the Yashwant Cooperative Bank in Maharashtra’s Phaltan, as a result of its liquidity condition and a “lack of concrete efforts” to address concerns.

When a bank fails, depositors get paid through the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation. That amount, capped at Rs1 lakh for decades, was raised to Rs5 lakh in 2020, after the crisis at the Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank. So, anyone with deposits up to Rs5 lakh in the failed bank would recover all their money. But, for deposits above that amount, there is no recourse. In the case of Rupee bank, 99 per cent of depositors recovered their money. However, in the case of Durga bank, only 95.8 per cent depositors are entitled to full compensation; for Ajantha bank, this is 91.55 per cent.

The failure of so many cooperative banks raises questions like whether your money is safe in a cooperative bank.

Critics say monetary and penal action is taken from time to time against commercial banks, too, but the sheer number of UCBs (1,463 and 448 in Maharashtra alone, as opposed to 135 scheduled commercial banks) makes things look distorted. Nevertheless, experts agree that corporate governance and compliance are among the major issues that have hurt the urban cooperative banking sector.

“Look at Yashwant bank or New India bank,” said Chaitanya Vaijapurkar, a retired banker and adviser to several cooperative banks. “Corporate governance is a big issue in both. Basically, alleged frauds by certain executives and board members led to the crisis. The smaller the bank, chances are, the weaker the governance. In large banks, the expectation is that corporate governance will be strong, but if that is not the case, we get crises like at New India and PMC bank.” He also said that the RBI, being a regulator, “to a certain extent, should have known about the issues”.

In 2019, the PMC bank crisis sent shock waves across the sector. The UCB had lent money to a bankrupt developer and it was alleged at the time that dummy accounts were used to hide the exposure. The crisis led to the Banking Regulation Act being amended in 2020 to grant the RBI more regulatory powers over urban cooperative banks. The major amendments were in areas like management, audit, capital, reconstruction and amalgamation.

In 2024, the RBI issued a master direction on fraud management for urban cooperative banks, which contain comprehensive guidelines related to reporting of fraud, following of principles of natural justice, governance mechanism, implementation of early warning mechanism, staff accountability, fixation of responsibility of third parties and role of external and internal auditors.

“The RBI has taken steps to bring UCBs [to the] mainstream step-by-step, whether it is a format for the balance sheet or disclosure norms,” said Satish Marathe, founder member of Sahakar Bharti, an NGO in the cooperative sector, and also a member on the board of RBI. “Earlier, circulars used to come for all scheduled commercial banks, small finance banks and payment banks. UCBs were never added. Now, a common circular comes and in many cases, what is applied to commercial banks gets applied to UCBs, too. That is a major change.”

He further noted that at all banks, including UCBs, asset recognition and provisioning is now systems driven and therefore divergences have reduced to a large extent. Also, he said, each bank is now assigned a senior supervisory manager and any digression is looked at seriously. This, insisted Marathe, has led to strengthening of many banks. According to the Financial Stability Report released by the RBI on June 30, 2025, the capital position of UCBs has continued to strengthen with their CRAR (capital to risk weighted assets ratio) touching 18 per cent as of March 2025, from 16.5 per cent in March 2023. The gross NPAs of UCBs have come down to 6.1 per cent as of March 2025, from 8.9 per cent in December 2024 and 8.7 per cent in March 2023.

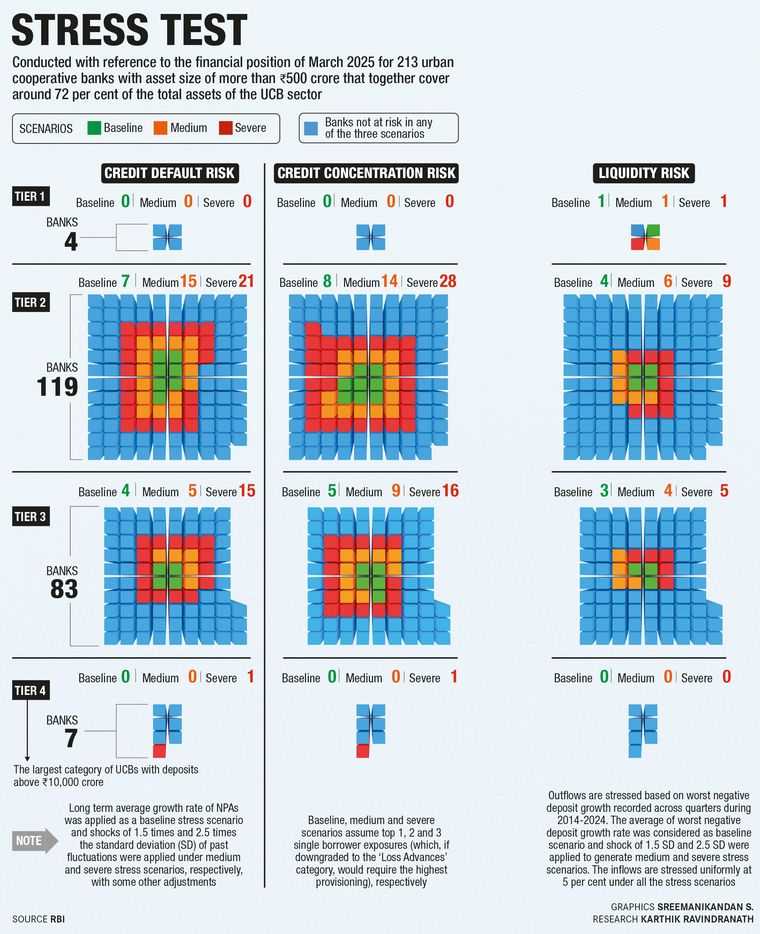

Stress tests were conducted on 213 UCBs with assets size of more than Rs500 crore to assess credit risk, interest rate risk and liquidity risk based on their financial positions as of March 2025. It was found that one bank in Tier 4 (the largest category of UCBs with deposits above Rs10,000 crore) would not be able to meet minimum regulatory requirement of 11 per cent CRAR under severe stress for credit default risk and for credit concentration risk. But, for Tier 2 and Tier 3 UCBs, the impact of credit risk and credit concentration risk under severe stress would be significant.

The Central bank has revised some lending norms for UCBs. They are required to follow the prescribed glide path to have at least 50 per cent of their aggregate loans and advances comprising of small values—not more than Rs25 lakh or 0.4 per cent of their core capital, whichever is higher, subject to a Rs3 crore per borrower limit. Also, aggregate exposure of UCBs to residential mortgages, other than those eligible to be classified as priority sector, shall not exceed 25 per cent and aggregate exposure to real estate sector, excluding housing loans, shall not exceed 5 per cent of total loans and advances.

Marathe feels there is also a need for UCBs to reconsider lending practices. “Lending based on collateral is a folly,” he said. “You need to study revenue streams of potential borrowers, whether they will be able to service instalments and interest over a period of time.”

Prabhat Chaturvedi, the CEO of the National Urban Cooperative Finance and Development Corporation (NUCFDC), felt UCBs need to focus on smaller-ticket loans. “Look at commercial loans below Rs1 crore,” he said. “There, delinquencies are far lower.…”

The NUCFDC is an umbrella organisation, set up based on the recommendations of former RBI deputy governor N.S. Vishwanathan-led expert committee, for examining issues at UCBs. An NBFC, it has a paid up capital of Rs270 crore and plans to raise Rs300 crore in total in the first phase.

Chaturvedi said turnaround time—time taken to process loan applications—was much higher in UCBs compared with commercial banks and non-banking financial companies, which was also hampering growth and competitiveness.

UCBs also face issues raising capital, which impacts their ability to expand credit. With banking deposit interest rates falling and people increasingly moving towards investing in mutual funds, it is becoming difficult for commercial banks, as well as UCBs, to garner low cost deposits.

The RBI has recently released a discussion paper exploring new avenues for UCBs to raise capital. One additional area being explored for UCBs with deposits of more than Rs10,000 crore is issuance of special share certificates to their members. While these shares will carry the same face value as member shares, they will be without voting rights and will not offer membership rights to investors.

The NUCFDC is looking to address multiple issues in UCBs like getting qualified and trained personnel, compliance, governance and technology.

“In technology, in compliance, in governance and legal all banks don’t have the kind of manpower [required] and many smaller UCBs don’t have the financial muscle to afford the kind of talent they need,” said Chaturvedi. “Also, even if they raise their budget, people may not be keen to go and work in small and mid banks in interior locations. How are we solving this two-way problem? We can recruit that resource and it can be available to banks on a shared basis.”

Marathe agreed that manpower issues hamper UCBs. “Look at some of the top Tier 2 and Tier 3 UCBs,” he said. “Many were formed 30-35 years ago and many employees have risen through the ranks. The skill sets they have are not sufficient for today’s banking, which is much more complex than it was even five years ago. They also lack exposure and all these are challenges.”

The NUCFDC has recently launched a Sahakar PaathShaala, a national level training and capacity building initiative for UCB employees across levels.

Technology upgradation at UCBs is a major priority for the NUCFDC. “Setting up centralised IT infrastructure can lead to cost efficiencies,” said Chaturvedi. “Look at UPI payments. If technical declines are more than 3-5 per cent of total transactions, there is a penalty by the NPCI (National Payments Corporation of India). Improving on technology [can avoid] the penalty. Similarly, if IT posture improves, compliance, governance and transparency will also improve.”

Meanwhile, after issues at various banks, whether at UCBs or commercial banks, the RBI is increasing scrutiny of board meetings at banks, which some experts said was the need of the hour. “Lot of discussions in board meetings may not get minutised,” said Vaijapurkar.

“Unless minutised, for the RBI it becomes an analysis after things have happened. In cooperatives, many times decisions are unanimous, essentially taken by one person. All this needs a drastic change.”

The number of UCBs reduced from around 1,926 in 2004 to under 1,500 in 2024. Marathe says closure of some “bad eggs” is good. But, we must clearly distinguish banks facing issues because of bona fide reasons, where there is scope for course correction, from ones that are stuck owing to malafide reasons, he said.

“A few bad apples with lack of integrity spoil the name of the sector,” said Saraswat’s Thakur. He also stressed that the bank, which has acquired seven smaller UCBs in the past, will ensure that those involved in the New India bank fraud are brought to book and that justice is done.