A Bengalurian loses 234 hours a year idling in the city’s congested roads—that is nearly ten days lost to traffic. It is not much different in India’s other metropolises. The daily commute is often an ordeal, as cities groan under the weight of overpopulation and inadequate infrastructure. But a futuristic solution is approaching at take-off speed—flying taxis and electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft.

With zero tailpipe emissions, low noise levels (around 55 decibels—similar to casual conversation) and the ability to move above the chaos on the ground, they offer a compelling alternative to ground-based travel. They are no longer a far-fetched idea, and are seen as a realistic and scalable solution for short-distance urban journeys.

The global eVTOL market is poised to hit $87.6 billion by 2026, growing annually at 37 per cent. The UAE, the US and Japan are fast-tracking air mobility policies, infrastructure and certification processes. Urban planners are already incorporating vertiport designs into development plans, highlighting a paradigm shift in city planning.

In India, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) has taken steps to enable this transformation. In 2024, it established six internal working groups focused on airworthiness, flight operations, vertiport design and navigation procedures. In September, it released comprehensive guidelines for constructing and operating vertiports—including charging infrastructure, safety systems, and visual landing aids.

At the forefront of India’s eVTOL evolution is Sarla Aviation, a Bengaluru-based company co-founded by German entrepreneur Adrian Schmidt. The firm plans to roll out its services in India’s tech capital by 2027 or 2028, starting with airport transfers.

“Think about routes like Airport to Electronic City—currently a two-and-a-half-hour drive, but less than 20 minutes by air,” says Schmidt. “We believe the next generation of mobility won’t be bound by roads.”

Despite only about 8 per cent of Indians owning a car, in urban centres like Bengaluru, mobility has become a test of patience. “Flying taxis will go the same way mobile phones did—initially costly, eventually ubiquitous,” he says. “This isn’t a luxury product; it’s infrastructure for the future.”

Sarla’s first eVTOL aircraft is designed to carry six passengers and a pilot. It uses distributed electric propulsion—six propellers with dual-motor redundancy to ensure safety. Even in the rare case of total motor failure, fixed wings allow for glide landings. The aircraft is optimised for trips between 20–30km but is capable of covering 160km at speeds of up to 250km an hour.

Sarla is designing its fleet specifically for Indian conditions—both geographical and economic. “We’re building this here, for here,” says Schmidt. The company has developed a full-scale prototype and a half-scale technology demonstrator, and is gearing up for flight testing.

Its phase 1 strategy focuses on predictable, high-demand routes—airports, IT parks, hospitals and luxury hotels. A rapid-response medical transport service is also in the pipeline and, says Schmidt, it will be offered free of charge. Over time, as miniaturisation and automation improve, Schmidt envisions door-to-door air mobility, where two-seater eVTOLs could take off from rooftop pads—“something like an autorickshaw of the sky.”

Sarla is currently collaborating with the DGCA on a phased certification plan. The regulator has developed a multi-tier framework for eVTOLs, targeting readiness by 2026. Initially, commercial pilots—primarily those with helicopter licences—will operate the aircraft after undergoing four to six weeks of additional training. In the long run, autonomous flight will likely become the norm.

The company is also working with Bengaluru International Airport to identify air corridors and develop centralised, high-speed charging hubs, ensuring aircraft are charged in sync with daily operations.

On the international front, California-based Joby Aviation is emerging as a powerhouse in the eVTOL space. In June 2025, Joby successfully conducted a series of piloted flights in Dubai. The company began working on Federal Aviation Administration certification in 2018, and is currently progressing through the fourth of five stages in the US regulatory process.

“Dubai is not just a test bed—it’s a proving ground for operational logistics, maintenance and certification readiness,” says Anthony Khoury, general manager, UAE, Joby Aviation.

Joby has also introduced the Global Electric Aviation Charging System (GEACS), an open-source, ultra-fast charging protocol that supports a wide range of electric aircraft, from urban air taxis to regional electric planes. Its infrastructure partnerships include Skyports in Dubai, where vertiport construction is already underway, and Delta Air Lines in the US, which is helping identify key landing spots across cities such as New York and Los Angeles.

The firm’s commercial strategy is threefold: direct operations in major cities; aircraft sales for defence and business applications (including a $1 billion MoU with Abdul Latif Jameel for 200 units in Saudi Arabia); and regional partnerships with global players such as Uber, Virgin Atlantic, Toyota and ANA.

Meanwhile, Chinese eVTOL giant EHang made history in March 2025 when its subsidiary received the first air operator certificates for human-carrying, pilotless aircraft from China’s civil aviation authority. Its EH216-S has since completed its first unmanned, passenger-carrying flight in Indonesia with support from local aviation authorities.

The company is starting with short-haul, low-altitude flights for tourism and urban sightseeing in Guangzhou and Hefei, but it intends to scale up into commuter services as regulations evolve.

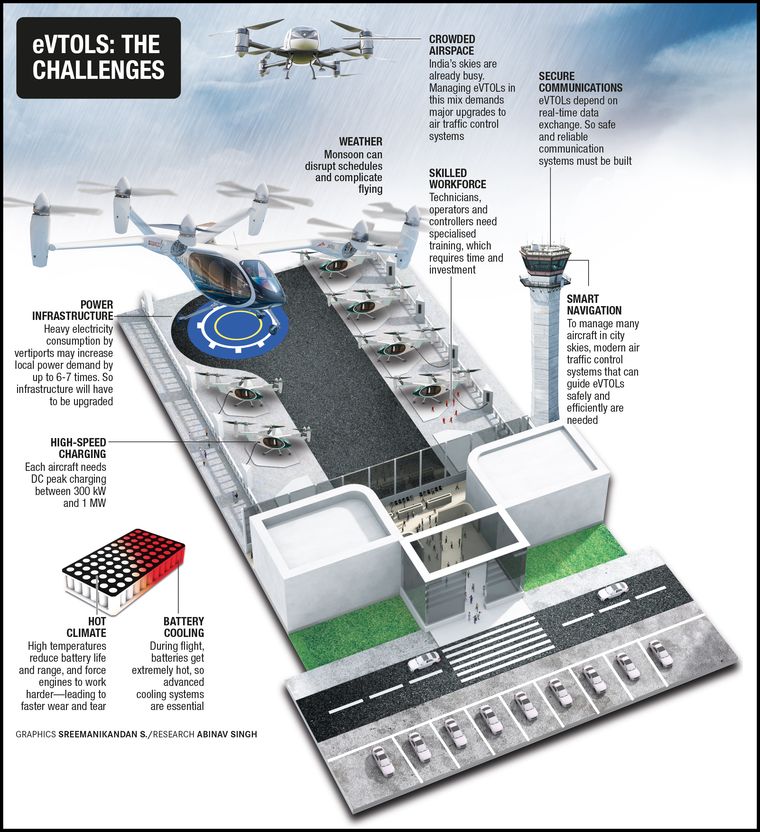

Despite the buzz, flying taxis remain a regulatory challenge. eVTOLs operate like hybrids—taking off vertically like helicopters, cruising like aeroplanes—and thus defy traditional aircraft classifications. This makes pilot training, flight rules and air traffic management far more complex.

In October 2024, the FAA introduced a new aircraft category—powered-lift—for such vehicles, its first in 80 years. The rules are designed to accommodate unique flight patterns while maintaining safety benchmarks, including requirements like black-box installation and emergency water-landing protocols.

The FAA and Europe’s EASA are also working to harmonise global certification standards. A coalition of five countries—the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—has launched a shared roadmap for the certification of Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) vehicles.

India, too, has made commendable progress. The DGCA’s guidelines now specify everything from structural design standards to cockpit instrumentation, emergency procedures, and even battery charging station placement at vertiports. State governments are being roped in to identify potential vertiport locations and safe intra-city routes.

Experts believe that point-to-point flying taxi services could begin within the next three years, with broader commercial rollout in five. But much depends on the pace at which governments develop regulations, build infrastructure and support local innovation.

India, with its overburdened roads, tech-savvy population and ambitious urban goals, is a natural candidate for this leap. And if all goes to plan, a decade from now, the humming above your office or apartment might be a flying taxi, ferrying passengers through the skies, far above the gridlock below.