There are defining moments in the lives of nations—like wars, famine and revolutions. There are similar moments in the lives of individuals and families—like the birth of a child, a wedding or moving to a small house after retirement. For the missus and me, the last shift to a modest three-bedroom apartment was indeed a reality check.

While calculating the blessings of living in a compact home, we had sadly overlooked one important aspect. Our books! Books we have lugged around for decades across the country on different postings. Books of fiction, science, science fiction and verse. Books on cookery, crockery, crookery and worse. Books we have read or intended to read. Books we thought we should read but never did. Books we have kept only because they were nice titles to flaunt—like the eight volumes of the Mahatma by Tendulkar (Dinanath Gopal, not Sachin Ramesh).

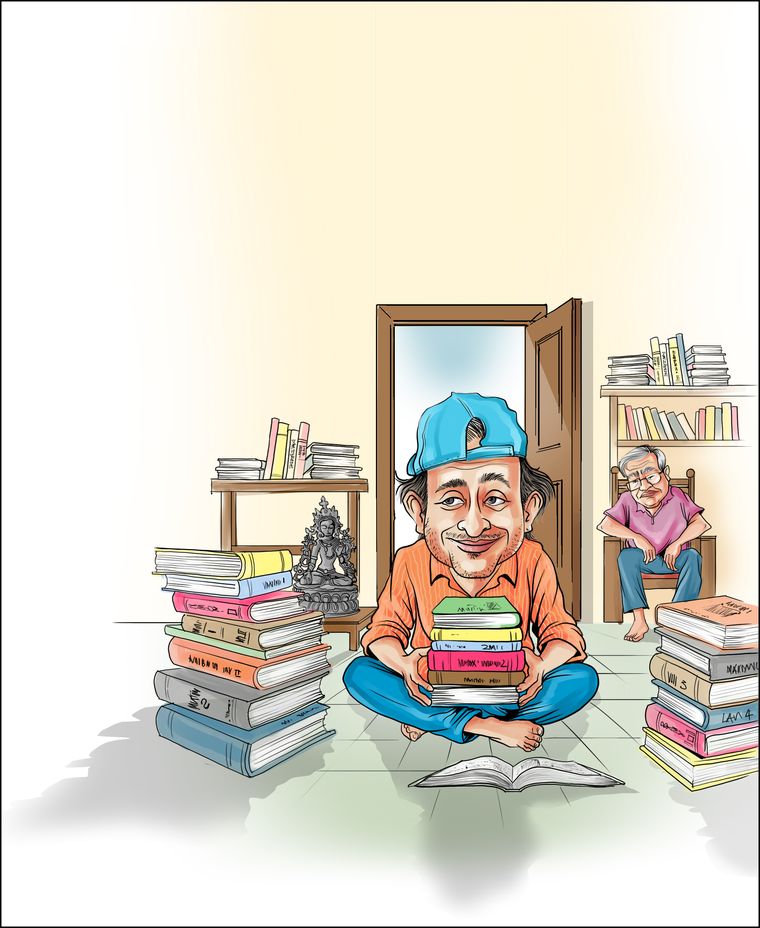

Therefore, when we moved to the cramped quarters, our books overflowed from the shelves onto tables and chairs and to the floor. We had to place books on the bed and the dresser and even atop the fridge. But we still couldn’t reach a satisfactory arrangement for all the books—books written by Washington Irving and Irving Wallace; by K.M. Munshi and Munshi Prem Chand; by Agatha Christie and Emile Zola. Sadly, we concluded that we would have to drastically reduce the number of books if we were to have moving space in our home.

I asked our neighbours if any of them would like to take any books. None replied, except the taciturn weirdo from next door. He whispered through the wire screen that he would gladly take any Marx. I apologetically informed him that I had only The Communist Manifesto, which I offered to give immediately. He burst out laughing. “Surely you jest, brother. I didn’t mean Karl Marx. I meant Ted Marks!” His merriment confused my wife, while I pretended that I had never heard of the literary giant named Ted Marks.

Months passed and we still needed to shuffle books around before we sat down for dinner or lay down to sleep. In desperation, I took all the popular fiction to a nearby school. The prim headmistress happily accepted the Enid Blytons, the Jane Austens, the H.G. Wells, the Conan Doyles and the Ayn Rands. Unfortunately, I failed to warn her that The Arabian Nights collection in six volumes was the unexpurgated version. A week later, the lady indignantly summoned me to school and berated me for half an hour for trying to corrupt the unblemished souls of her wards. I couldn’t blame her. After all, the poetic lasciviousness of The Arabian Nights will enchant any adolescent!

We then tried to leave the bestsellers on a bench in the park, with a note inviting residents of our condo to help themselves. While not a single Chase or Wodehouse was taken, the maintenance staff complained to the Residents Welfare Association that we were leaving trash across the countryside. The association warned us against littering or clogging the garbage chutes and bins with our ‘junk’. Suddenly I realised that our books were proving to be more difficult to get rid of than Siward’s corpse in Macbeth!

As a last resort, the missus decided to call Nawab, the raddiwala (also referred to as the kabadi), who buys scrap and waste for pennies in our colony and sells them for gold mohurs somewhere else to make his fortune. We segregated the books, retaining our favourites, the rare ones and others of sentimental value. With a heavy heart, we stacked the rest near the front door for the kabadi to take away.

Nawab arrived and inspected the books. He also examined an idol of Tara that we keep near the entrance. I had purchased this exquisite piece on an impulse years ago, at a price that I could barely afford. But recently an expert in such matters had told me that the idol could now be worth a fancy amount.

Tentatively, Nawab asked, “What is this made of?” and I proudly informed him that the idol was made of ashtadhatu, the alloy of eight metals.

“Oh!” said Nawab, “Had it been plain brass, it would have fetched you a good price. It must be about 20 kilos, so at Rs300 per kilo, I could have offered you Rs6,000. But ashtadhatu…,” and he shook his head disapprovingly.

He then picked up a few books and declared that they were useless. “The page size is too small—I can offer only Rs2 per kilo,” he said. He took another book and, while I cringed, he tore off a page and scrunched it in his fist. “See,” he said, “This paper is too old. It is unusable for making thongas—the paper bags for loose merchandise.” Quite ruthlessly, he also wrenched off the hard covers of the library editions, declaring that he did not need cardboard.

Much after Nawab had left, I remained sitting in a chair near Tara, with the leftover books and a few torn hard covers strewn on the floor.

“It seems what we consider priceless is actually worthless!” I said tearfully.

The missus, sitting beside me, said softly, “Don’t feel downhearted, dear. The value of the same thing can be vastly different in different universes.”

K.C. Verma is former chief of R&AW. kcverma345@gmail.com