If the brain were a grand Indian household, the cortex would be the talkative uncle with opinions on everything, the lobes would be the siblings arguing over territory, and the brainstem would be the old, silent grandmother sitting in the corner—saying nothing, doing everything.

And if the brainstem is the old grandmother of the nervous system, then the midbrain is her sharp-eyed middle-aged son: quiet, alert, always watching, rarely speaking, but missing nothing.

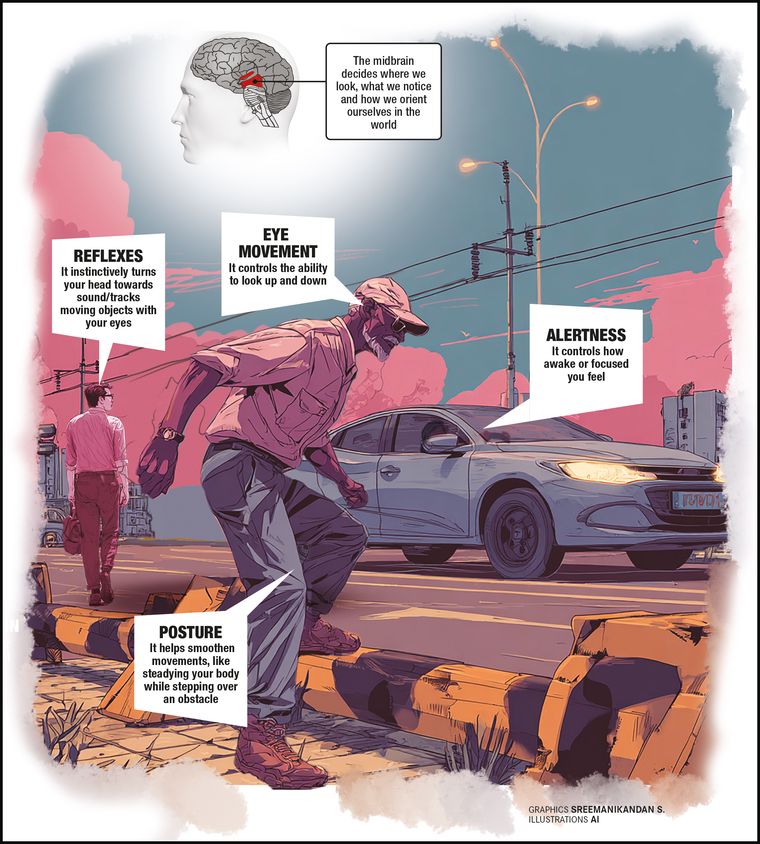

The midbrain occupies a precarious position as the top floor of the brainstem. It is small, central and unforgiving. It sits between thought and survival, linking the higher brain above to the ancient machinery below. It governs eye movements, posture, reflexes, alertness. It decides where we look, what we notice, and how we orient ourselves in the world. It is not interested in drama, only efficiency.

Patients with midbrain problems rarely arrive with complaints that sound serious. They come with oddities. “Doctor, my eyes don’t move the way they used to.” “I feel awake but strangely detached.” “I keep bumping into things I can see.” The symptoms feel vague until anatomy gives them meaning.

A retired schoolteacher came to see me with his wife, both immaculately dressed, both slightly irritated with each other in that way only long marriages manage. His hair was neatly oiled, his spectacles spotless. He sat upright, composed, and mildly offended by his own body. “I can read perfectly,” he said, “but I cannot look up to meet my wife’s eyes when she scolds me.” His vertical gaze was restricted, his eyelids heavy, his reflexes subtly altered.

His MRI showed a small brain tumour nestled deep within the midbrain—a glioma. In neurosurgery, there are few words that instantly quiet a room like that one. Not because it is always aggressive, but because of where it lives. A midbrain glioma is not something you chase. It is something you respect.

This is not a place for heroic resections or dramatic gestures. The midbrain does not tolerate enthusiasm. The safest surgery here is often the smallest one—a navigation-guided biopsy, planned meticulously, executed gently, and stopped early.

On the day of surgery, the atmosphere in the operating room was noticeably different. No rush. No bravado. The navigation system became our compass, mapping a precise, minimally disruptive path through safe corridors. Each movement was deliberate, each decision weighed. We burred a small hole in the skull and cut the dura. The biopsy needle advanced millimetre by millimetre, guided by coordinates registered before we started. The tissue was sampled, haemostasis secured, and we withdrew. The surgery was brief; the responsibility wasn’t.

Postoperatively, the schoolteacher woke up unchanged—which, in this part of the brain, is the best possible outcome. His gaze limitation persisted. His dignity remained intact. His wife smiled with visible relief. “At least he can still hear me,” she said. He rolled his eyes sideways—a small victory for neurology and marriage.

The biopsy gave us clarity. Treatment followed. Life adjusted. He received radiation and then chemotherapy, which shrank the tumour substantially. His gaze improved over a few months. Now he could see right through her, and she wasn’t too happy with that.

The midbrain teaches surgeons a lesson early in their careers: That doing less can sometimes mean doing it right. That intervention does not always mean removal. That courage occasionally lies in knowing when to stop.

Evolutionarily ancient, the midbrain predates language and logic. It reacts before thought. It turns the head before fear registers. It is the reason we flinch, orient and attend. It reminds us that much of what keeps us functional operates beyond our awareness. And perhaps that is its quiet wisdom: That control is often subconscious. That survival does not require insight. That not all battles are meant to be fought head-on. The midbrain does not demand attention; it simply keeps you oriented, alert and alive. And sometimes, the best thing a surgeon can do is listen to that silence—and leave it undisturbed.

The author is consultant neurosurgeon at Wockhardt Hospital, Mumbai.

mazdaturel@gmail.com @mazdaturel