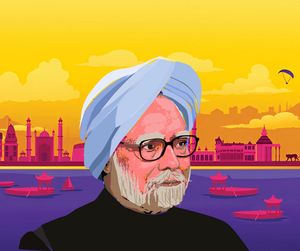

No prime minister of India made a more constructive contribution towards establishing an equilibrium between India and Pakistan than Dr Manmohan Singh. Building on the Islamabad Declaration of January 2004, proclaimed jointly by prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and president Pervez Musharraf, Singh initiated with his counterpart a process of sustained dialogue which yielded the most positive results, specifically with regard to the issue of Jammu and Kashmir that, but for the perversity of destiny, might have opened the path to lasting peace and harmony.

In initiating the process, Singh fully recognised that finding a via media to the vexed question of J&K would be the optimal way of settling other issues. It was further agreed that a quiet backchannel was essential to a result-oriented dialogue. Second, the interlocutors chosen by both leaders were not chosen because of their position in the bureaucratic hierarchy but because of the immense trust Musharraf had in a friend, Tariq Aziz, and Singh had in a retired former high commissioner to Pakistan, Satinder Kumar Lambah. They reported only to their respective principals.

Foreign ministers and others were kept in the loop on a “need-to-know” basis at the discretion of the two leaders, but directions on how to proceed came only from the respective heads. Over a period of about a thousand days, meeting at various locations outside the subcontinent, the two special envoys hammered out an agreement that built on two key bipartisan statements by Vajpayee and Singh: “insaniyat, kashmiriyat, jamhuriyat” (humanity, the Kashmiri way of life, and democracy) by Vajpayee, and bringing about a situation “where one could have breakfast in Amritsar, lunch in Islamabad, and dinner in Kabul” by Singh.

Although Musharraf summarised the agreement as a “four-point” programme, foreign minister Khurshid Kasuri’s detailed account of the negotiations (see his tome, Neither a Hawk Nor a Dove, backed in all relevant specifics by Lambah’s In Pursuit of Peace: India-Pakistan Relations Under Six Prime Ministers) shows that the number of points on which agreement was reached was close to 16 after taking the fine print into account.

The essence of what both sides accepted was that there would be no exchange of people or territories but that the Line of Control would be rendered “irrelevant” by freely allowing Kashmiris to cross the LoC in both directions to foster family relations, encourage fraternal friendships, promote trade and investment, and set up an inter-governmental mechanism to try to ensure similar levels of prosperity and democratic freedoms for all Kashmiris on both sides of the LoC. This was undergirded by the common understanding that there could be no independent, sovereign Kashmir.

This draft agreement, except for one issue to be ironed out by the two heads—whether to describe it as a “joint management” or “joint cooperative” mechanism—was readied to be signed when Singh visited Islamabad at the end of February 2007.

However, the Pakistan president got involved in a fracas over domestic issues with the chief justice of Pakistan (nothing to do with India or the draft), leading to the bar in all Pakistani courts striking in support of the chief justice who had embarked on a country-wide protest tour. This resulted in Singh’s visit being postponed by a month and then dropped indefinitely.

But signed or not, the backchannel agreement definitively established that sincere, sustained dialogue, even with a Pakistani military government, could generate positive outcomes—which surgical strikes and armed attacks deep into Pakistani territory never could achieve.

Instead of building on this enlightened initiative, Singh’s successor has shown how unenlightened he is by failing for over a decade to summon the wisdom and the courage to engage with Pakistan.

As this is his last column, the author thanks his readers for their patronage over a decade and more, and wishes them all a happy new year.

Aiyar is a former Union minister and social commentator.