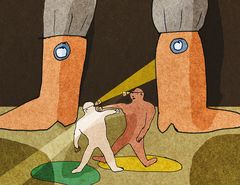

Union Home Minister Amit Shah thunders at the Chinese that India will not yield them “an inch” of Indian territory. His acolyte, Himanta Biswa Sarma, the spanking new chief minister of Assam, echoes him: “Not an inch of Assam will be conceded…. People have sacrificed their lives, but boundary has been protected, which we will continue to do at any cost.” No, he is not warning the Chinese. He is threatening his neighbouring state of Mizoram. This is his version of faithfully implementing Amit Shah’s impassioned call on July 25, at a meeting of northeast chief ministers in Shillong, to “amicably” resolve their border issues before the 75th anniversary of India’s independence.

The border dispute has nothing to do with India’s independence. Under the British rule, the Lushai Hills that now constitute Mizoram, were demarcated five times in the 19th century; but only once, in 1873, in consultation with recognised tribal leaders. Two years later, the Inner-Line Forest Reserve demarcation was gazetted. In 1952, the Lushai Hills were rightfully granted their Autonomous District Council under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. Then, under the wise leadership of Indira Gandhi, the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971, reconstituted the Lushai Hills district as the Union territory of Mizoram which, in terms of Section 6 of the Act, provided that “thereupon, the said territories shall cease to form part of the existing areas of the state of Assam”. Clear enough, one would have thought.

But that would be to reckon without Shah’s unique politics of “sowing hatred and distrust”, as Rahul Gandhi has reacted to the ghastly events on the Mizoram-Assam border that broke within 48 hours of the Union home minister fishing in troubled waters.

According to Mizoram Home Secretary Lalbiaksangi’s report to the Union home ministry, the Assam Police arrived with a cavalcade of about 20 cars and ambulances at the Kawngthar Veng autorickshaw stand in Mizoram’s northernmost city of Vairengte, and while the CRPF stood mutely by, fired tear gas shells and smoke bombs at the Mizo police detail, and then brought in further reinforcements leading to the exchange of fire in which several police personnel and civilians were injured and even killed.

The Assam Police also brought with them tents and building materials to set up a camp in the nearby reserve forest area. Is this an “amicable” manner of settling disputes whether over land or, as Sarma has alleged, over protecting reserve forest land from encroachment? Remember, Sarma is a Shah favourite and, despite being a defector from the Congress, has ardently embraced the BJP doctrine of “divide and rule”.

As the northeast’s most distinguished journalist, Patricia Mukhim, has put it, “statesmanship of a high order” is needed (The Shillong Times, July 29). It was statesmanship of that order that resulted in Rajiv Gandhi’s Mizo Accord of 1986, which ended the 20-year-old insurgency and brought sustained peace in Mizoram. The chief ministers who have maintained that record include the current second-term chief minister, Zoramthanga. He was once the No.2 in the insurgency and knows a thing or two about sustained armed rebellion that seems to have escaped his Assam counterpart’s attention.

Informed statesmanship would have required Shah to let sleeping dogs lie. By setting an arbitrary deadline to bring Assam’s border issues with six of its neighbouring states to finality, he was only provoking the kind of armed clash that occurred on the Mizoram-Assam border on July 26. The borders have been where they are for the last half-century. “Statesmanship” would require leaving it at that.

The writer is a former Union minister for the development of the north-eastern region.