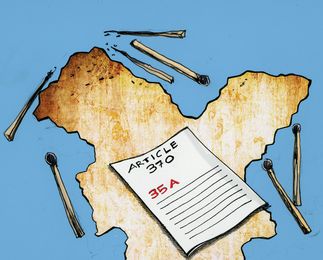

I was in Kashmir and Ladakh last week. The whole state is simmering; not just the Muslims and the separatists, but literally everyone—the Kashmiri Pandits, the Ladakhi Buddhists, the Jammu Dogras and other Hindus. There is not a section of society that is not agitated. It is not any specific political move or newly introduced draft legislation, nor even a court judgment that bothers them. It is the mere act of the Supreme Court determining a date for hearing a petition brought to the court by a little-known NGO in May 2014, in the immediate aftermath of the Narendra Modi government being sworn into office. The issue is the constitutional validity of Article 35A.

The story goes back to 1889. In that year, the durbar (Kashmir government) decided to change the language of administration from Persian to Urdu. The result was a mass influx of Urdu-speaking Punjabis into the riyasat (principality), ousting the elite Kashmiri Pandits and Jammu Dogras from their monopoly of government posts. This led to strong, organised protests from the Kashmiri Pandit Sabha and the Dogra Sabha demanding that “outsiders” not be permitted to permanently reside in the state, take government jobs, buy or sell properties, or avail of government scholarships and other welfare facilities. Initially, the Maharaja did not lend his ears to such demands, but started becoming concerned when it appeared that British settlers were seeking to put large investments into buying land, to avail of what Jawaharlal Nehru was later to describe in the Parliament as the “delectable” climate of the valley.

So, in 1927, the Maharaja issued an order in which he defined the term “hereditary state subject” and made it illegal for any “non-state subject” to be a property owner or avail of special privileges reserved only for state subjects. Meanwhile, the equally alarmed Muslim majority community threw itself into the agitation, with Sheikh Abdullah emerging as their leader.

The demand that this protection be retained indefinitely figured largely in the negotiations between Sheikh and Nehru, that led to the Delhi Agreement of 1952. A key point of the Agreement was Nehru’s solemn undertaking to not interfere in the arrangements on state subjects operating since 1927. In 1954, this undertaking was granted constitutional status through a presidential order issued under Article 370 numbered 35A and annexed.

That position has been sustained for the better part of seven decades. Now, with the valley sitting on a powder keg, is the worst possible time to take up the highly contested, extremely complicated legal issues involved in even considering, let alone decreeing, a judgment on this matter.

The information divulged in an address by Satinder K. Lambah—former High Commissioner of India to Pakistan—at the Annamalai University, last month, showed that the fears in the state are entirely justified. Lambah demonstrated that in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pak-occupied Kashmir, the removal of protection over land rights of state subjects by former Pakistan president Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq resulted in transmogrifying the demography. In 1948, 85 per cent of Gilgit-Baltistan’s population comprised local Shias and Ismailis. But, as a result of Zia removing such protection, Pashto- and Punjabi-speaking Sunni non-state subjects now constitute over half the region’s population.

This is the fate that awaits state subjects of Jammu and Kashmir of whatever religious persuasion, should our saffron Zias have their way.

Aiyar is a former Union minister and social commentator.