As advocate Chandru reads the newspaper, back straight, legs crossed, a tentative Alli reaches for another newspaper to mimic his actions. Seeing the little girl do this, Chandru shakes his head and smiles. Alli smiles back. They both get back to their papers.

This is one of the most widely shared images of the recently released Jai Bhim, but it holds a deeper meaning for Dr C. Sasikala, a senior assistant professor of anatomy at a government medical college in Tamil Nadu.

In 1994, Sasikala, then a young student from a backward village in Pappireddipatti town panchayat in Dharmapuri district, had gone to Chennai to study medicine. She got admission in a private college through the government quota. However, when she and her father reached the college to join the course, the administration backtracked and asked her to pay a huge fee.

Helpless, Sasikala reached out to Chandru through members of the Students’ Federation of India, and he approached the Madras High Court on her behalf. There was no immediate reprieve, and he asked her to write an improvement exam for class 12 and try again next year. She wrote both the school and medical entrance exam the following year and joined Chengalpattu Medical College.

Chandru eventually won the case and the court ordered the private college to pay Rs40,000 in compensation to Sasikala. The college released the money, but it did not reach her. (She did not want to reveal why). Chandru stepped in and covered her expenses till she became a doctor. His house was her second home, and he was like a father to her. After completing her MBBS, Sasikala earned a diploma in clinical pathology and an MD in anatomy. On watching Jai Bhim, she was reminded of her days in Chandru’s home; she sent him the Chandru-Alli image from the film, saying: “This is you and me in the picture, sir.”

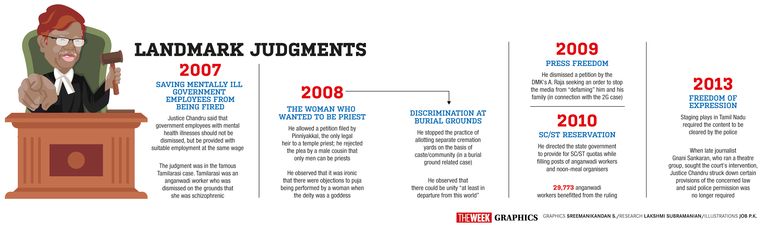

Chandru Krishnaswamy, on whom the Suriya-starrer is based, later become a popular judge in the Madras High Court and passed several landmark judgments. These include allowing women to be priests in temples, removing caste considerations from burial grounds and protecting government employees with mental health illnesses from being dismissed. He would hear at least 75 cases a day, and cleared 96,000 cases in six and a half years.

Contrary to what some might think of the legal profession today, Justice Chandru was always simple and modest. On his day of retirement from the Madras High Court, he submitted a final declaration of his assets to acting chief justice R.K. Agrawal (now president, National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission), returned the key of his official car and walked out clad in a traditional dhoti and shirt. He crossed the road to visit his old office, headed to the railway station, bought a season ticket and took a local train home. He had politely refused a formal farewell ceremony, but visited his fellow judges in their chambers to say goodbye.

He had also vowed that he would neither practise in the Supreme Court nor head tribunals. Upon retirement, he immediately vacated his official residence, moved into a two-bedroom apartment in nearby Mylapore, and took up teaching.

Chandru’s modest office, in Alwarpet, Chennai, welcomes visitors with a sign: “Don’t remove your footwear.” Next to the sign is a seated stone Buddha with two yellow flowers on his shoulders. Inside, the walls are lined with books and mementos, among them a dry peepal leaf and a brick wrapped in polythene. “It is the Uthapuram brick. And the leaf is from Jallianwala Bagh,” said Chandru.

In 2008, when the state government demolished the Uthapuram wall in Madurai—created to separate the living areas of caste Hindus and dalits—Chandru had observed in a judgment: “Uthapuram wall is no Berlin Wall. When the Berlin Wall crumbled, no one wept for the fall of the wall.” He was referring to the caste Hindus’ resentment over the wall being demolished.

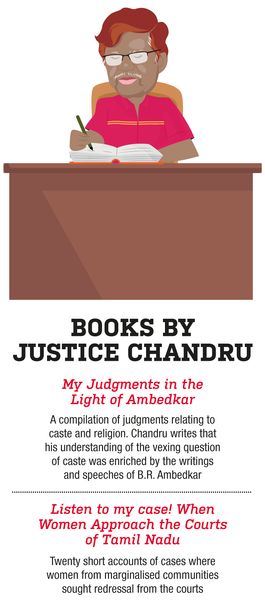

For Chandru, who turned 70 this May, the law is a weapon for people to ensure that their social rights are protected. He has, in particular, taken up several cases for women, including the Parvathi case shown in Jai Bhim. His book, Listen to My Case! When Women Approach the Courts of Tamil Nadu, outlines the stories of 20 women from marginalised communities and their fight for justice. Even now, in 2021, he feels that the gates of the judiciary are yet to open up for women.

EARLY LIFE

Chandru was born in a middle class orthodox family in Srirangam, Tiruchirappalli, on May 8, 1951. He has an elder sister, and is the third of four brothers. His father, an Indian Railways employee, moved the family to Chennai when Chandru was a schoolboy; soon after, he lost his mother. He was put in a Ramakrishna Mission school in T. Nagar.

When they were in Chennai, there was extreme scarcity of food, and the siblings would wake up at 4am to join the long queue at the ration shop. Chandru still wakes up at 4am.

After his father refused to remarry, Chandru and his younger brother started helping with household chores. In time his elder brothers moved abroad, his sister got married and his father died; by then Chandru had learnt to live on his own. He sent his younger brother to live with his sister and moved into a hostel in Chennai.

Growing up, he was spellbound by the speeches of Dravidian leaders. There were days when he had to starve and sleep at the doorstep. “If we returned home late, we would not get food,” he recalled. “But then, the discourse was more important.” Though his family was religious, Chandru started questioning their beliefs after being exposed to Periyar Ramasamy and the Dravidar Kazhagam.

When he joined Loyola College in Chennai for a BSc in botany, the DMK was in power. The city was a hotbed of student agitations, mostly in support of the DMK. But, Chandru had moved on. He wanted a wider worldview. He started reading more about global politics and soon organised rallies against the Vietnam War.

Another hot issue was the Keezhvenmani massacre of 1968—44 Dalits were locked in a hut and burnt, allegedly by landlords over a wage dispute. “This was really shocking. What crime did these innocent people commit?” said Chandru. “I wanted to begin a new movement. This is when I came across leftist leaders. I joined the CPI(M) for two reasons: I liked their ideology and they were staunchly anti-Congress at the time.”

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) was more attractive to him as he had grown up on anti-Congress slogans. Plus, it was part of a global movement. This was when Chandru became a student leader and founded the Chennai wing of the Students’ Federation of India.

His activism cost him, though. He was thrown out of Loyola College in his second year for organising student agitations. This was when future editor N. Ram and future economic adviser to the E.M.S. Namboodiripad government in Kerala, Dr Mathew Kurian, took him to the Madras Christian College. He completed his degree there, but got even more involved in politics.

As he was single, he travelled statewide for the next two years, addressing meetings and mobilising students. “I call these two years my open university,” he said. The SFI grew stronger, too.

This was when the Annamalai University in Chidambaram conferred upon Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi an honorary doctorate. The students’ movement protested, asking why the leader was being given a doctorate when the graduates were without jobs. The police cracked down on the students and Udhayakumar, a student of BSc mathematics, was killed.

The government set up the Justice N.S. Ramasamy commission to look into the incident. When the inquiry began, Chandru visited Ramasamy and asked him to quit because he was too junior. “He asked me on what grounds I was asking him to step down,” said Chandru. “I did not know the provisions of the law then.”

Because he was a thorn in the government’s flesh, lodge owners in Chidambaram were apparently told to not give him a room. Chandru shuttled by bus between Pondicherry (where he had found a room) and Chidambaram—around 60km—to depose before the commission. This was when Chandru asked his friend, future Union minister P. Chidambaram, to help him with his argument. The commission finally concluded that the body was that of Udhayakumar, but ruled out police excesses. Impressed by Chandru’s work, Ramasamy encouraged him to pursue law.

LAWYER AND JUDGE

Advocate K.K. Venugopal (now Attorney General of India) was instrumental in Chandru taking up law. There were two connections—Venugopal and Chandru’s elder brother, Dr K. Rajagopal, were friends; Chidambaram was Venugopal’s junior. When Venugopal visited Rajagopal in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, he asked the elder brother to persuade Chandru to take up law. Chandru agreed, thinking that law college was the best place to continue with his politics. Venugopal helped him join the Government Law College in Chennai.

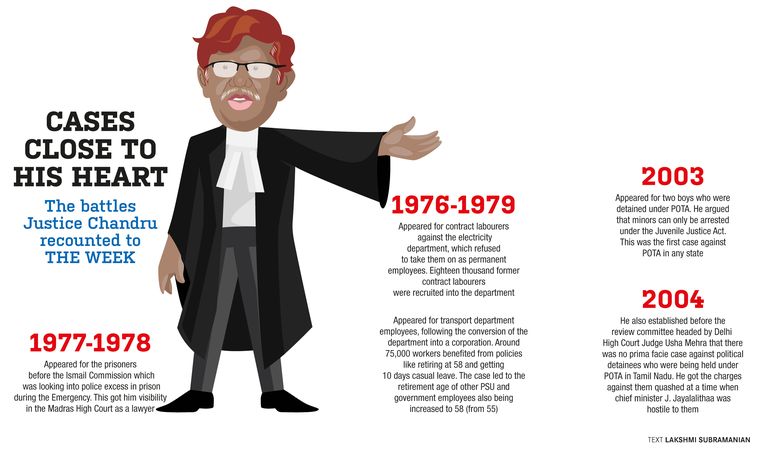

By the time Chandru was into his third year there, Emergency was declared. “Prime minister Indira Gandhi called Gujarat and Tamil Nadu the islands of indiscipline,” said Chandru. “The Karunanidhi government was dismissed. I accompanied E.K. Nayanar and others on their way back to Kerala. I then moved out of my hostel and went on strike.” This is when Chandru resolved to graduate in law and practise it. The Emergency gave him the experience of going to police stations and filing bail applications.

After graduating, Chandru joined a law firm called Row and Reddy. They were barristers who had returned from the UK to work for the poor. Soon, CPI leader Mohan Kumaramangalam and others joined Row and Reddy, and it became a leading law firm in Chennai.

The agitator in Chandru was still active. He led a protest in the Madras High Court, soon after joining Row and Reddy. “For the first time, we organised a procession from the High Court, demanding free elections after the Emergency. More than 200 robed lawyers marched down the street,” he said.

He quit Row and Reddy after eight years, when the firm started taking up cases for companies. In 1983, he set up his own chambers and expanded his practice beyond labour matters.

His tryst with the CPI(M), too, ended a few years later. When the Indian Peacekeeping Force was deployed in Sri Lanka, he criticised the CPI(M)’s support for it. “In 1988, the CPI(M) expelled me,” he said. “The party supported the Indo-Sri Lanka accord. But I opposed it saying, how could a third party, in this case India, sign an agreement?”

Once, when Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer met Namboodiripad on a flight, he asked the latter to bring Chandru back into the party. The chief minister told the jurist that Chandru must appeal to the party’s control commission. A disappointed Krishna Iyer later told Chandru: “We are not red enough for them. Let us start a pink party.”

Since then, Chandru concentrated a lot more on the courtroom. Though he led several protests involving lawyers, he became convinced that boycotting courts was not the answer. The courts are for litigants, not lawyers, he declared. For this, one of the lawyers’ associations he once headed expelled him.

In Jai Bhim, a scene depicts this change of heart. Suriya, mid-protest, jumps the police barricade and heads back to court to argue a case. It showed his transformation from an agitator to a defender of rights.

Chandru also got married around the same time. “I was 32 and he was 41 when we fell in love and got married,” said Bharathi, a former professor at Pachaiyappa’s College, Chennai. “We were two old adults.” It was a simple marriage at a registrar’s office.

Chandru became a senior advocate in 1996 and started taking up more criminal cases, especially those under the Prevention of Terrorism Act and Terrorism and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act. He took up several human rights cases, and found himself fighting the then J. Jayalalithaa government on many occasions.

It was around this time that he took up tribal woman Parvathi Rasakannu’s case, which inspired Jai Bhim. Said Chandru: “When Parvathi’s case came up, I was handling a lot of women’s cases and education-related matters.” He had gone to Neyveli to address some teachers, when Parvathi came to him with her daughter. A young volunteer had brought her to meet him. She said her husband was missing. He asked her to meet him at his office, as it was getting late for his bus trip back to Chennai.

The following weekend, Parvathi showed up at his office and narrated her story. She had seen her husband being tortured in custody before he “went missing”. Chandru filed a habeas corpus in the Madras High Court.

“The Cuddalore SP and other officers were summoned,” he said. “They told the court that her story was not true and that Rasakannu had escaped from custody. The judges said that Parvathi should search for her husband, so I quoted the Rajan case in Kerala (where a missing engineering student’s father had filed a habeas corpus). Then the court adjourned for vacation. I told Parvathi that we should look for Rasakannu’s nephews, who were also missing. When the court reopened, there was a change of bench. Justices P.S. Mishra and Shivaraj V. Patil took over.”

Chandru knew that Justice Mishra was strictly against police brutality. He had earlier held four policemen guilty in the 1992 Padmini rape case, so there was hope for Parvathi. “Mishra and Patil told the advocate general that they could not believe the defence,” said Chandru, “And so, the case took a turn.”

Though Jayalalithaa had opposed his judgeship, calling him a “terrorist lawyer”, Chandru fought many such cases en route to becoming a judge in the Madras High Court in 2006. There, too, he tried to be an agent of change. “I used to reach 15 minutes before and leave one hour after court proceedings were over. I tried to increase court hours,” he said.

At a time when many judges spent the first quarter of the day in admission matters, Justice Chandru would not hear lawyers until he wanted to dismiss the matter. He would finish off admission matters between 10:15am and 10:30am and then take up the final hearing cases. He would also classify cases and take them up accordingly.

If Jayalalithaa did not approve of him, what did Karunanidhi think of his judgeship? “When my book, My Judgments in the Light of Ambedkar was released, he wrote a long piece in the DMK’s mouthpiece Murasoli celebrating it,” he said with a smile.

Chandru’s acquaintance with Karunanidhi began during the Emergency, when he visited the jail where M.K. Stalin and others were detained. He had moved High Court saying that political detainees were entitled to visitors like any other prisoner. Chandru also appeared before the Ismail commission set up to investigate jail brutality during the Emergency. Later, he also appeared for Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leader Vaiko, when he was arrested under POTA in 2002.

Cases apart, it was his work ethic and the way he carried himself that impressed many of his peers. Chandru, who was made a permanent judge in 2009, would ask lawyers to not address him as ‘My Lord’ in court. He did not want a mace bearer to announce his arrival in court and refused a personal security officer (PSO) because he thought it had become “more of a status symbol rather than being based on any actual threat perception”.

When a police officer asked him to reconsider, he said: “We have 60 judges with four constables on rotation at the house. That means 240 people. Then each judge has one PSO. That means there are 300 people at the disposal of judges. The whole of south Madras can be defended with 300 constables.”

He never accepted gifts from his clients or colleagues. A board in front of his office said: “There are no deities here, no flowers should be brought; no one is hungry, no fruits; and no one is shivering, no shawls.”

One of his standout judgments came in October 2007, when he overturned the dismissal of anganwadi worker A. Tamilarasi. The Tuticorin district administration had removed her because she was “in insane medical condition”. She had paranoid schizophrenia. Tamilarasi’s father had died in November 2002, her brothers had moved out after getting married and she was the only one supporting her mother.

Chandru came down hard on the administration for using the phrase “insane medical condition” to justify her dismissal, saying it did not find any place in relevant statutes. The judgment shielded government officials from being dismissed for having a mental condition.

In My Judgments in the Light of Ambedkar, Chandru shares a note on the judgments he passed while on the Madurai Bench. In one case, he had ordered the state transport corporation to revoke its decision to not halt government buses near a dalit colony before entering Sivanandipatti village in Tirunelveli district. The district police chief had feared a law and order issue if dalits occupied all the seats before caste Hindus could even board the bus. It is a regular bus stop now.

MAKING OF JAI BHIM

“I have read Chandru sir’s books and he is a man who used the law as a weapon to protect the rights of the common man,” actor Suriya told THE WEEK. He first heard of Chandru a few years ago, when he was looking for trustees to guide his NGO Agaram—which helps the underprivileged get educated. “I understood that he was a person who, once, would write God’s name several times, and then later he discovered Periyar and Ambedkar. I was amazed to see a person like him,” said Suriya.

Jai Bhim director Tha. Se. Gnanavel knew Chandru even earlier. When he was a journalist, Gnanavel wrote several articles on Chandru’s judgments and the cases he fought as a lawyer. He had always wanted to turn Chandru’s life into a movie, perhaps even a documentary.

Once, when the two were on a train to Neyveli—after Chandru’s retirement—the jurist told him about the Parvathi case. He took Gnanavel to Kammapuram village near Virudhachalam, showed him the police station and explained how Rasakannu’s body was disposed near the Tiruchirappalli district border.

When Chandru retired in 2013, his close friends thought that there would definitely be a documentary on him and his judgments. Chandru initially dismissed the idea, saying, “I only did my job.”

But after the train ride, when Gnanavel wrote a script and showed it to him, Chandru greenlit the concept. He also helped in detailing the movie. For instance, the courtroom in Jai Bhim, a copy of the one in the Madras High Court (shooting is not allowed in the higher courts), was designed based on Chandru’s inputs. The scene where Sengeni (Parvathi in real life) sits on the court steps as the rain lashes was shot at The American College in Madurai; it is a colonial building and resembles a court. The corridors of the court were those of the Public Works Department office in Chennai.

Chandru also added his own twist: When Suriya argues in the court, photos of Justices Krishna Iyer and Sathyadev—two of Chandru’s role models—hang on the walls.

While Gnanavel had got Chandru on board, he was worried about the budget. Also, he did not want it to be a hero-centric movie. “The story and screenplay are the heroes in this movie,” he said. He was looking for an actor who was willing to do a role with “no romance and no fight scenes”. He knew Suriya through Agaram, and approached him to produce the movie. The actor was impressed with the script and offered to play Chandru.

Gnanavel, though, had one condition; the script would not be tampered with to make Suriya look like a superhero. Suriya agreed. “It automatically became a big budget film,” said Gnanavel. “We roped in big artistes, including Prakash Raj.”

Said professor Kalyani, who is associated with Suriya and Agaram, and was one of the witnesses in the Parvathi case: “I am very happy about the film. Suriya was able to capture the nuances in Chandru’s character (like Chandru, he rarely smiled). The film has brought to the limelight the crucial issue of not just custodial violence, but also false cases foisted on the tribal communities, which continues even today.”

Several youngsters, who felt that the legal profession had lost its dignity in recent years, reached out to Gnanavel after watching the movie. “Many students are asking me for guidance to take up law,” he said.

Praise has poured in from not only critics and viewers, but also Chandru’s associates, including Chief Justice of the Andhra Pradesh High Court P.K. Mishra. Bar Council of Tamil Nadu Chairman P.S. Amalraj wrote to Gnanavel saying: “The movie has brought to light not only the struggle for justice by a poor victim, but also highlighted the strength of the legal profession and the greatness of courts of justice to come to the aid of victims whose rights get trampled due to abuse of power.”

There were several messages from family and friends, too. Chandru’s grandnephew called him up from Brazil and told him that he wants to be a lawyer. The most touching message, however, was from his dentist daughter, Sakthi. She had once told him that she would never become a lawyer. Her reason: If she made it, people would say it was because of her father; if she failed, they would say she failed him.

After watching Jai Bhim, Sakthi told him that she should have taken up law and asked him if she could still do it.