The right to be alone is indeed the beginning of all freedom,” said the American jurist William O. Douglas.

That precious little thing called privacy, which the Constituent Assembly did not include in the Constitution, which on many occasions knocked at the doors of the legal conscience of the nation, managing just a little toe in, has finally found its rightful place among the fundamental rights of the Indian citizen.

When a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court pronounced its verdict on August 24, proclaiming unanimously that privacy was a fundamental right, it marked the culmination of the evolution of the right to privacy in Indian jurisprudence. It had been a long journey—from the Constituent Assembly not including it among the fundamental rights, to the Supreme Court ruling that such a right did not exist in the Constitution, to acknowledging that it was integral to the right to life and liberty, to finally upholding it as a fundamental right.

While privacy has been upheld as a fundamental right, arising out of Article 21, the court has concluded that it is linked to all the other rights. This will profoundly change how fundamental rights are interpreted.

Defining privacy, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, who was a member of the Supreme Court bench, wrote that it was founded on the autonomy of the individual. “It enables individuals to preserve their beliefs, thoughts, expressions, ideas, ideologies, preferences and choices against societal demands of homogeneity,” read the judgment.

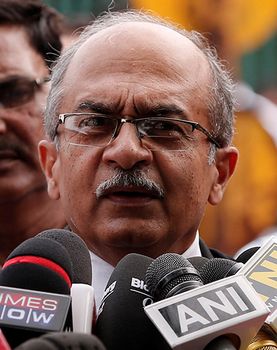

Prashant Bhushan | Reuters

Prashant Bhushan | Reuters

The judges did not catalogue the various aspects of privacy, leaving the concept open for future interpretation. Justice J. Chelameswar wrote that people would not like to be told by the state as to what they should eat or how they should dress or whom they should be associated with in their personal, social or political life. Justice Rohinton Nariman stated that apart from the privacy of one’s home and protection from unreasonable searches and seizures, privacy was now extended to protecting an individual’s interests in making vital personal choices such as the right to abort a foetus, rights of same sex couples, and rights to procreation, contraception, general family relationships, child rearing, education and data protection.

“The rights of the common man will undergo a dramatic shift after this judgment,” said senior lawyer Sajan Poovayya. “Any state action on a citizen will be tested on the touchstone of privacy.”

The court, however, said that just like the other fundamental rights, the right to privacy was not absolute. Any restriction on it would require the existence of a law, a legitimate need, and a proportionality between the aim and the means, said the Chandrachud judgment. The other judges stated that any breach of privacy would have to be justified by giving a reason that was just, fair and reasonable. Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul wrote that national security would be an obvious restriction, and public interest would be another.

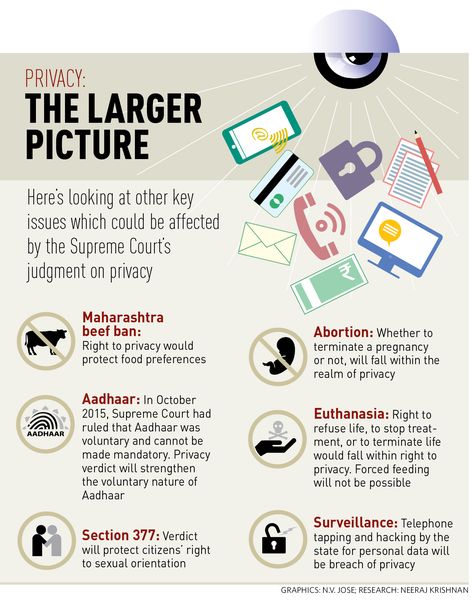

The judgment will have an impact on existing laws. The Aadhaar Act, providing for collation of data on citizens, including their biometrics, has already been challenged in court. A three-member bench of the Supreme Court is hearing the case, and the law will now be tested against the touchstone of the privacy judgment.

The government is taking heart in the court’s rider that there can be limitations to the right to privacy. “The government has been consistently of the view, particularly with regard to Aadhaar, that the right to privacy should be a fundamental right flowing from Article 21 and it should be subject to reasonable restrictions,” said Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad.

Nariman wrote that all laws that dealt with aspects of privacy would now be vulnerable. “Statutory provisions that deal with aspects of privacy would continue to be tested on the ground that they would violate the fundamental right to privacy, and would not be struck down, if it is found on a balancing test that the social or public interest and the reasonableness of the restrictions would outweigh the particular aspect of privacy claimed,” he wrote.

There will be implications on surveillance, phone tapping, the right of celebrities to not have their private lives intruded upon and even investigative journalism. “The government did not want privacy to be declared a fundamental right,” said activist-lawyer Prashant Bhushan. “An important ramification of the order is that the government will have to be careful while bringing laws that impose restrictions on citizens as it can violate privacy as a fundamental right.” For instance, the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, which does not allow unmarried persons to have surrogate children, could be challenged. The DNA Profiling Bill, which aims at setting up a DNA databank to be used as evidence during trials and to identify missing or unidentified persons, has been criticised for not meeting the required standards of privacy.

Social issues awaiting legal resolution, like the demand to decriminalise gay sex, are likely to be decided in the light of the judgment. “The right to privacy and the protection of sexual orientation lie at the core of the fundamental rights,” read Chandrachud’s judgment.

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises gay sex, was read down by the Delhi High Court in 2009. The court’s decision came on a petition filed by the NGO Naz Foundation. Section 377 pertains to sexual intercourse “against the order of nature”. The Delhi High Court, however, did clarify that it would continue to govern non-consensual sex involving minors. It was seen as a major victory for the LGBTQ community. But, on December 11, 2013, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court overruled the high court’s verdict.

The latest judgment found fault with this order. “Five out of nine judges spoke about Section 377, and found fault with the Supreme Court’s overruling of the Delhi High Court’s decision. They agree that sexual orientation is a private matter of the individual, and it is protected by his or her right to privacy,” said Anjali Gopalan of Naz Foundation.

Chelameswar cited the examples of force-feeding of certain persons by the state and keeping a critically ill person alive against his or her wishes as issues of privacy. “An individual’s rights to refuse life prolonging medical treatment or terminate his life is another freedom which falls within the zone of the right of privacy,” he said.

In what could have repercussions on the beef ban, which has been legally challenged, the court said food habits of citizens lie in the zone of their right to privacy. “...liberty enables the individual to have a choice of preferences on various facets of life including what and how one will eat, the way one will dress, the faith one will espouse...,” the judgment said.

A two-judge bench of the Supreme Court, hearing cross-appeals against the Bombay High Court’s order decriminalising possession of beef in case the animal was slaughtered outside Maharashtra, said the judgment would have “some bearing on these cases”.

Flagging the threat to privacy in an increasingly digitalised world, the court has emphasised the need for a regime for data protection. The government has set up an expert committee chaired by Justice B.N. Srikrishna to draft a data protection law.

Kaul’s judgment referred to the disclosures of Edward Snowden, a CIA whistleblower, to drive home the point that the growth and development of technology had created new instruments for the possible invasion of privacy by the state, including through surveillance, profiling, data collection and processing. He also wrote about the capacity of non-state actors to invade home and privacy. He warned against both the state and non-state actors using big data to control people and said there was an unprecedented need for regulation regarding the extent to which such information could be stored, processed and used by non-state actors. There was also a need for protection of such information from the state, he added.

The judgment could have a bearing on the case over the social messaging service WhatsApp sharing subscriber data with parent company Facebook. “The private players as well as the state will have to establish that privacy is not being breached, and if it is being done, on what exceptional grounds,” said Supreme Court lawyer Aishwarya Bhati.

The onus is now on the government to create a legal framework that protects privacy.