The irony was inescapable. December 15 was supposed to be the deadline for 98 cities selected under the smart cities project to submit their plans to the urban development ministry. A fortnight before the deadline, what India put on global display instead was exactly how unsmart its cities were. Ushering in winter, Delhi was cloaked in a smog so thick that visibility was down to 50 metres at places. Visibility, however, was the least of the worries of its 1.68 crore people, who were left gasping in a cocktail of pollutants. The particulate matter (PM 2.5) load alone was in the region of 216 micrograms per cubic metre—3.6 times the safe standard as per Indian norms.

Meanwhile, down south, Chennai was flooded and marooned in a record-breaking rainfall for over a week. The helpless city watched the clouds emptying themselves over it, bleakly aware that with its silted rivers, pathetically inadequate stormwater drainage and all those swank constructions over erstwhile aquifers, there was nowhere for the water to go, except enter homes and inundate streets. Cemented compounds, which were heat traps in summer, were as useless in the rains, preventing any percolation.

The toll of the Chennai floods stands at 270 and counting. Death by smog cannot be counted so quickly—its effects are insidious, corroding the respiratory system and triggering off respiratory diseases in the short run, and cancer in the long haul. One estimate by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) says there is one death per hour due to air pollution-related diseases and the lungs of every third child is impaired.

Only a year ago, Srinagar, situated in the Himalayas, down whose slopes water cascades with felicity, found itself flooded in over ten feet of water at places. The valley had been drenched with an unprecedented amount of rain, but that was not its tragedy. The tragedy was the sure and steady encroachment of wetlands around the city, its natural sponges that soaked up excess moisture. Add to that the choking up or diversion of water channels, and it was no wonder that the city was left to stew in the floodwaters.

It is all very fine to cry “climate change” every time nature acts capricious. It is entirely another matter for cities to compound natural climatic excesses with their own stupidity—which is what Indian cities are doing right now. The urban unravelling of India is a result of what we have not done for decades. “After Chandigarh in the 1950s and Navi Mumbai to some extent in the 70s, urban planning has never been taken seriously,” says Pratap Padode, director of the Indian chapter of Smart Cities Council, a service aggregator and adviser for smart cities. “When clouds dump 490mm rain in 24 hours, any city is bound to be inundated. But there is no reason for the water to accumulate there because it has nowhere else to flow into.”

Chennai had the bizarre scene of municipal workers pumping out flood water, but finding no place to deposit it, what with the three rivers and whatever lakes remain brimming over. Chennai’s growth as the Detroit of the east and as a software hub has come at the price of its wetlands. Newer areas of the city like Velachery and Siruseri have come up on erstwhile marshes; even its airport at Meenambakkam is on the floodplains of the Adyar river. A CSE study shows that the metropolis has 2,887km of roads but only 855km of stormwater drains.

“Chennai’s civic officials once used to boast of their stormwater drain network, saying no amount of rain could flood the city. They were right. Old Chennai had only ankle-deep water, while the post-2000 developed areas sank under several feet of water,” says Shailesh Pathak, urban planning expert and executive director, Bharatiya Urbania, a real estate development firm. “Puducherry, which is nearby, received similar rain, but it didn’t collapse, because the French laid a good infrastructure that is still adequate for the present population. In Chennai, the civic works didn’t keep pace with above-ground constructions.”

It was not as if Chennai had no warning. 2005 is remembered as the year of the Mumbai deluge, a wake-up call for the city. It was also the year of the worst rain in Chennai in sixty years, causing floods, though not as severe as the present one. While Mumbai woke up to the need to clean up its act, at least partially, Chennai let its growth story progress unhindered by interruptions like retrofitting and detailed development plans (DDP). According to Sadanandh, president of the Association of Professional Town Planners in Chennai, DDPs for newly developed areas like Velachery and Ambattur are yet to be prepared.

Changing times throw up new issues. Some of these seem negligible irritants initially, but unless authorities have foresight, the irritant could end up being the proverbial nail in the horseshoe for which the kingdom was lost. One fluttering polythene bag is an eyesore, one environmental warning that polythene can persist un-degraded for 500 years is alarmism. But when tonnes of these polythene bags choke storm water drains, it results in the city that never sleeps coming to a dismal halt, says Padode. That is what happened to Mumbai on July 26, 2005, proof of which was evident when conservancy workers raked out piles of these bags from drains.

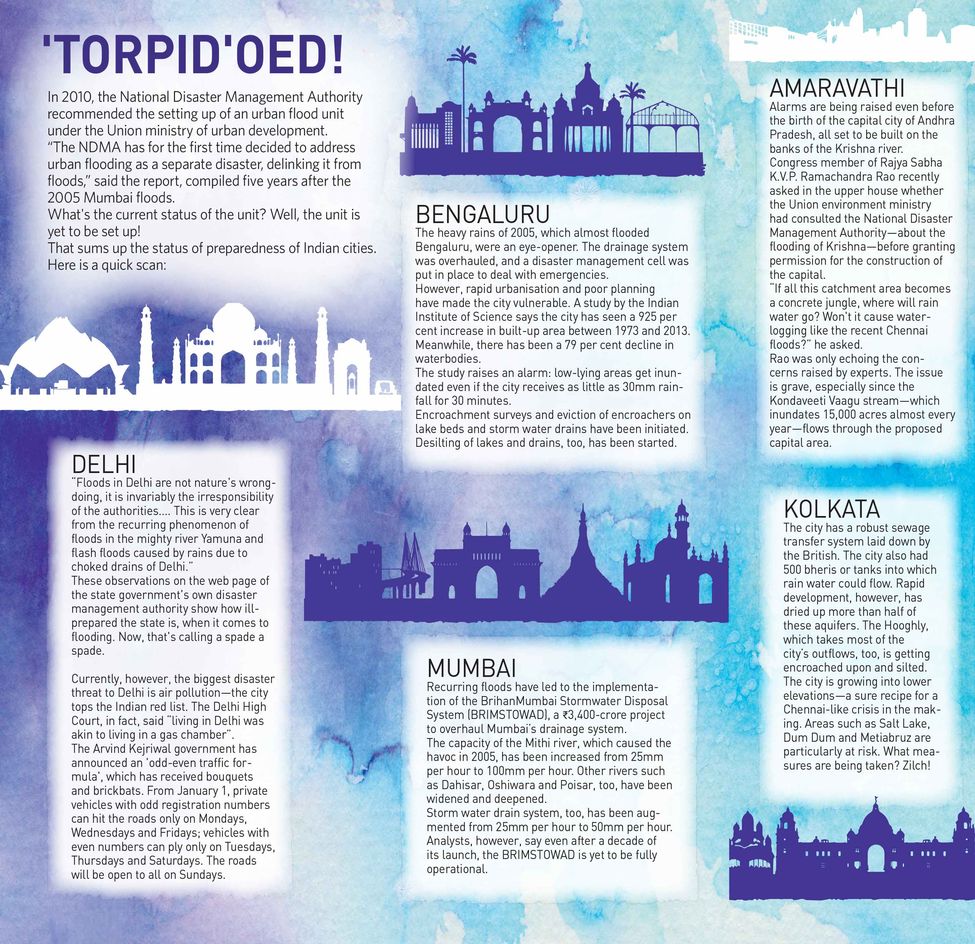

Mumbai has spent a lot on flood-proofing the city with expensive fitments and pumping stations (see box on page 65), but it still has not given enough thought to the polythene issue. Will all efforts come to naught again next time because polythene bags reign?

Bengaluru is sitting on an urban disaster, which may well be catalysed by its burgeoning garbage. Three years ago, residents of Mandur village, which has the city’s official landfill, erupted in protest against Bengaluru’s NIMBY (not in my backyard) attitude, having to live with the ugly side effects of the silicon city’s growth story. Though the agitation made international headlines with even The New York Times commenting that the capital of India’s modern economy was drowning in its own waste, neither technology nor manual effort has gone into dealing with the 5,000 tonnes of garbage the city generates daily, which is disposed of haphazardly. The Mandur landfill has closed down, and N.S. Ramakant, member of the Solid Waste Management Roundtable, says unless biomining of Mavallipura and Mandur landfills begins, the city will continue to sit on a time bomb. It took the scare of the plague to transform Surat from squalid to sparkling; what will it be for Bengaluru?

When Kolkata was first built, the site chosen was an elevated land. So, even though the city is close to the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, it never got flooded. But Kolkata is growing—alarmingly fast and rather blindly. It has a robust sewage transfer system laid down by the British, which is able to manage the present 980 million litres generated daily. Kolkata traditionally also had 500 bheris, or tanks, into which rain water could flow. New development is drying up these aquifers; only half the original number are left. The Hooghly, which accepts most of the city’s outflows, too, is getting encroached upon and silted.

Worse, the city is spreading towards the lower elevations, a sure recipe for a Chennai-like crisis. Areas like Salt Lake, Dum Dum and Metiabruz are particularly at risk. Kolkata is a city of activists. Its mayor Sovan Chatterjee says the people will never let the city lose its greenery, which is both a sponge for extra rainwater and a filter for the increasing pollution. He has also initiated a modern drainage sewage system for the city, though funds are always an issue. As a city that has already been listed as vulnerable to climate change and rise in sea levels, will Kolkata’s little initiatives be enough to deal with its massive growth pangs?

Activists and urban planners believe the time for cosmetic changes is long past. Desperate times call for desperate measures. The Delhi government’s plan to reduce car load by half through the odd-even licence plate formula for alternate days may throw up several implementation issues, but many believe it is a step in the right direction. Delhi and neighbouring Gurgaon’s recent experiments with car-free days, though localised and limited in scope, have already proved how much cleaner the air can become with fewer cars on the road.

But why did the city allow itself to reach this cataclysmic stage? The efforts to change all buses to the relatively cleaner compressed natural gas (CNG) in the early 2000s came to a naught with the increase in personal cars, many of them diesel-run. “Building more roads and flyovers is only encouraging more cars. Anyway, it is a traffic management issue, not an environmental one. Only a slim per cent of office-goers use cars, around which the entire city infrastructure is built,” says Pathak.

Public transport has been given second preference, with neither last mile connectivity being addressed, nor any incentive being given to give up cars. One report actually says that several bus routes in Delhi were discontinued due to traffic congestion (read private cars).

What is a problem in Delhi today could become the crisis in another city tomorrow. Mumbai, despite being a seaside city, is seeing a rise in air pollution, especially in winter. Bengaluru, with its five million cars, is on its way to the choking stage. Rather than wait for the worst-case scenario, these cities should have started cleaning up their act while they still had time, say experts.

Urban vulnerability, however, is not linked to one factor alone. If clean air is Delhi’s most critical issue right now, extreme cold and extreme heat are equally urgent issues. “It is established that there will be more extreme weather events because of climate change. While we cannot avoid them, we need to make our cities more resilient to them. In fact, disaster management should be at the core of any smart city plan,” says Padode.

At a recent event, Ahmedabad Municipal Commissioner D. Tara said the city had a tie-up with an American weather agency to predict extreme heat days. The municipal corporation ensures that public water fountains work on those days, warns offices in advance about the heat wave and even identifies cool spots and parks where people could go to. “This reduces cases of heat stroke and even death. But since there are no figures for mitigation, the efforts don’t get the attention that a tragedy gets,” she said.

There have been other positive changes. Improved cyclone warning by the meteorological department and effective coordination among authorities reduced death toll in recent cyclones like Phailin and Hudhud. The latter battered Vishakhapatnam, but the toll was only 26. Activists, however, point out that the Rs8,000 crore economic loss, too, could have been mitigated had the casuarina tree breaks, planted after the 2004 tsunami, been maintained and not fallen prey to land sharks.

Again, just as cities on the eastern coast are vulnerable to cyclones, Delhi and Mumbai are prone to earthquakes. The big Himalayan temblor is still waiting to happen. “What have we done to retrofit our cities for quake resilience?” asks Pathak. “Nothing.”

Not every retrofitting is an expensive exercise. Several buildings that were constructed before the present seismic norms came into effect can be retrofitted by wrapping the walls in wire mesh and adding another layer of plaster to them. These initiatives, however, require a smartness that has not been woven into the urban fabric yet.

WITH DNYANESH JATHAR, TARIQ BHAT, PRATHIMA NANDAKUMAR, LAKSHMI SUBRAMANIAN, LALITA IYER AND RABI BANERJEE