Recollections of the partition have always been intensely personal, with Indian and Pakistani victims reliving their traumatic memories. Partition Voices by Kavita Puri is not entirely different. What sets the book apart is that it focuses on the victims of the partition who are now British citizens. Denys Wild from Croydon, Surrey, was an officer in the Punjab Frontier Force. His love for his adopted homeland was so enduring that he chose to return to India in 1949 and spent the next 25 years at a tea plantation in Assam. “Mountbatten was a pretty ruthless man,” said Wild, and he “made sure it did go through quickly. If everybody had taken another six months or so, a lot more could have been sorted out.”

In the summer of 1944, nineteen-year-old Denys Wild boarded a scruffy steam train heading north towards Dehradun, in the foothills of the Himalayas – home to India’s Military Academy (IMA), where officers were trained for the British Indian Army. At around four in the morning word came round that everyone had to get off. The engine was struggling, and the passengers, including Denys, were made to push the train up to the top of the hill. Then they all jumped back on and went on their way. This is Denys’s first memory of India.

Denys arrived at Dehradun, in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, in June. Since the early 1930s the IMA had trained a handful of Indians to be officers. Denys was among the first group of British officer cadets to be trained with them. At the entrance to the building is an engraved plaque, reminding cadets of their duty:

The safety, welfare and honour of your country comes first – always and every time.

The safety and welfare of the men you command comes next – always and every time. Your own welfare and safety comes last – always and every time.

Training lasted six months. Denys learned to swim, drive, use a weapon, plan for battle, and how to speak Urdu, the lingua franca of the Indian Army. He trained, ate and lived alongside the Indian cadets: ‘We got along very well.’ Every Saturday morning there was a parade: ‘It was all very pukka, with a band.’ Denys was a colour bearer, carrying the regimental standard, alongside another cadet who held the Viceroy’s colour. ‘We thought it was very grand because as we stood in the middle of the parade there is a certain stage when whoever the inspecting officer was had to stop and salute us. Well, he wasn’t saluting us, of course, he was saluting the flag, but it was quite nice to think he was saluting us. And when Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, who was the Commander-in-Chief in India came along, he then stood there and saluted us. I think we were quite proud of ourselves.’

Following his training, Denys had a choice: to be with the British Army, the British service attached to the Indian Army, or with the Indian Army. Denys chose the latter. His Urdu, thanks to his munshi’s (teacher’s) tutelage, was fluent. The Indian Army paid more, was prestigious and frankly quite ‘exotic’. But there was something deeper too. Denys had grown up near Addiscombe, in Croydon, Surrey, which was once home to the British military academy that trained the private army of the East India Company. The streets near his childhood home had names such as Outram, Havelock, Elgin, Clyde and Canning – after soldiers and politicians prominent on the British side during the 1857 Indian uprising (or ‘Mutiny’). Growing up, hearing this history, Denys believes rubbed off on him, and influenced his decision to join the Indian Army, a decision which resulted in a lifelong relationship with India.

On 10 December 1944, Denys joined the 13th Frontier Force Rifles, which was part of the Punjab Frontier Force. He proudly has his regimental tie on when we meet. He was first sent to the command centre in Abbottabad, seventy-five miles north of Islamabad, where he was responsible for training new recruits. There were four main separate companies of Indians: the Pathans; Muslims from the Punjab known as ‘PMs’ – Punjabi Musalmans; the Sikhs; and the high-caste Dogras who were nearly all Hindu. Denys recalls that on inspections you could never allow your shadow to fall on the Dogras’ cooking pots otherwise they would have to throw the food away.

Denys stayed at the command centre for just a few months before being sent on jungle training, and was then finally sent on active duty, first to Burma, along with the PMs and the Sikhs of his regiment, then on to Singapore, Sumatra and back to Burma again. When the war ended Denys held the rank of captain, with three pips on his shoulder.

In July 1945, in Britain’s first general election for ten years, Clem Attlee’s Labour Party came to power with a mandate to withdraw from the subcontinent at the earliest opportunity. End of colonial rule in India also spelled the end of the existing British Indian Army and its administration. Field Marshal Auchinleck oversaw the division of this force. Around 260,000 soldiers, mainly Hindus and Sikhs, went to India. And around 140,000 soldiers, nearly all Muslims, went to the Pakistan Army. The Brigade of Gurkhas, recruited in Nepal, was split between India and Britain. Denys and his good friend Major George Bowyer offered to take the troops in their regiment back to their families in the Punjab and make sure they were all properly paid and pensioned. For their part, the sepoys invited Denys and George – the sahibs – to visit their villages in the Punjab. Over a period of twenty-eight days on the eve of independence, Denys and his friend travelled across the Punjab to bid their men farewell.

The homes of the sepoys, Denys remembers, were mostly mud houses built of wattle and cane. They had thick walls and were cool inside. Family members would splash water on the outside walls to keep them fresh. He remembers these mixed communities where the village well was a meeting place, just as post offices were in English villages. He vividly recalls a modern canal system – gesturing as he describes to me how each village well had a sophisticated system of buckets in a circle and how a camel or bullock would walk around as the buckets entered the well and came up with water. It was a simple life. And that life was good. It appeared that everyone got on. He and George visited the mixed village of his Sikh naik (corporal), who was getting married. It was a boisterous affair, as many of the Sikh males ‘had been on the booze’ and got on horses and rampaged through the village past the Muslims while they were observing Ramadan. Denys felt their Muslim neighbours may have been offended, but no offence was expressed. He reflects that it is hard to believe that in just a few weeks’ time these lands of Punjab were to become execution grounds.

It is the visit to his batman, or orderly, Mohammed Sarwar, however that Denys particularly cherishes. In early August 1945, Denys travelled by rail from Lahore a hundred miles west to the village of Pindi Hashim to visit him. As the train passed through the stations he noticed huge crowds. After making some enquiries he discovered that Mahatma Gandhi was on his train. Denys says he thought he may have been travelling through the Punjab appealing for calm in the weeks ahead of partition. When the train stopped Denys got out to see what all the fuss was about, and there he saw the Mahatma standing on the steps of his carriage. Denys was in his jungle-green uniform – the only Britisher around. ‘I swear he [Gandhi] looked up and saw me and winked. But I may be quite wrong. I have always had that feeling that he winked at me.’

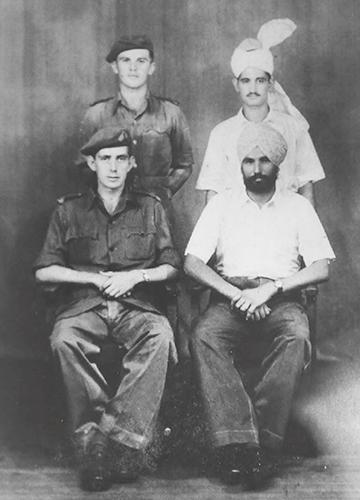

Mohammed Sarwar had spent two years as Denys’s batman, travelling everywhere with him. ‘He made sure my uniform was in order, that I had a cup of tea in the morning; he was the chap who kept me on the straight and narrow.’ Every officer had a batman. Denys communicated with Mohammed in fluent Urdu. He describes Mohammed as ‘quiet, unprepossessing, gentle. Just very respectful.’ Denys stills keeps a photograph of himself, Mohammed, George and Nihal Singh, his Sikh batman. The black and white image of the four men in their uniforms – Mohammed in a crisp white shirt, his head covered in a white headdress – hangs proudly in his study today.

Denys insists on getting all his photographs out from the loft to show me. He climbs up a rickety old ladder, and I am worried this ninety-two-year-old will hurt himself. I needn’t have been concerned. He returns with a cardboard box full of pictures: the officers playing cricket, a class photo of the Sandhurst cadets and the 1st Battalion, the Burma Regiment. Sitting in the centre is Captain Wild. Mohammed Sarwar is in the back row, standing on the far right in his regimental uniform.

Denys says he spent some of the most memorable days of his time in British India in Mohammed’s village. Pindi Hashim was surrounded by the lush Punjabi plains: ‘It was magic, actually.’ Each evening Denys would carry up a charpoy, a light bedstead, onto the flat roof where he would sleep under the stars. ‘It was lovely. It was nice and warm.’ Mohammed showed him around. Denys had never ridden a horse before, but went, carefully, alongside the more experienced rider, Mohammed, with people waving to him on his way. In the evening the two men sat side by side on the earth, a former British officer and his batman, eating a simple meal with their fingers of local vegetables and fresh chapattis, made by Mohammed’s wife.

When Denys and Mohammed parted, they both knew it was for the last time. ‘I don’t remember discussing it at all, but I’m sure we all knew in our heart of hearts that we wouldn’t see each other again,’ says Denys. ‘I couldn’t put my hand on my heart saying I remember being in tears or near to it saying goodbye, but I’m sure I was. Everything seemed to be happening so quickly at that stage. India was part of the British Empire. Then it suddenly became independent and everything sort of happened bang bang bang on top of the other. And I think there was probably very little time for emotion.’

After they said their goodbyes, Denys started his long journey back to England. On Independence Day he and George found themselves stuck in Lahore. Two days later it was announced that Lahore was to become part of Pakistan. The two men stayed at the prestigious Faletti’s Hotel on Egerton Road, just off the city’s famous and historical boulevard, ‘The Mall’. The hotel boasted electric lights and fans in every room. Out on the streets, Denys saw how the locals they came across ‘were full of joy at being independent’. He recalls people coming to shake his hand, saying to him: ‘Thank you for making us independent.’ But mostly Denys stayed in the hotel. They were not able to leave the city as the train station ‘was knee deep in bodies. Nobody could move.’ He was told: ‘Sit tight until it clears.’

One day a man charged into the hotel. It was Sir John Bennet, ‘Inspector General Police in Punjab, big wheel’. He had with him his Hindu driver; ‘probably hid him under the bed or something like that’ to keep him away from the mobs, Denys presumes. During this time, he and the other army officers, who were mostly the occupants of the hotel, kept out of sight as much as possible: ‘One just laid very low. Not for fear of any sort of reprisals or antipathy towards us, but the opposite, really. I don’t think we felt any fear of what had become Pakistani people attacking us or being nasty to us or anything like that. I think we just laid low because there was so much of a problem going on elsewhere.’

After a few days the officers received the all-clear to leave for the train station, and Denys and George began their journey back to Britain. They travelled through some of the places which had experienced some of the worst bloodshed of partition, through not only Lahore, but also Delhi and Calcutta. But Denys has little recollection of witnessing the horrors. ‘I think people of our age in those days were not exactly overburdened with thoughts about what was happening elsewhere in the country of India or what had become Pakistan. I think we were, it sounds self-centred to say so, almost ignorant of what was really happening on the nasty side.’

There was no question of Denys going out to help the disorder. He and George were on their own, using up the last days of their leave, his regiment about to be disbanded. ‘We were fairly thin on the ground by that time. Certainly British troops would have left India. British officers would have been in the process of being taken over by their counterparts of India (and Pakistan). Maybe they could have done more.’

With Indian independence, some British Army regiments were already on their way back to Britain. The alternative British initiative to quell the growing unrest, in July 1947, was a limited military force operational from 1 August 1947. The Punjab Boundary Force was at its peak a 25,000-strong contingent, led by British officers. The majority of the troops on the ground were from the polarised Punjabi Muslim and Sikh communities. It was a ‘toothless and dreadfully inadequate response to Partition’s violence’. They policed a 37,500 square-mile area with a population of 14.5 million across the twelve districts of the central Punjab. It was led by Major General Rees who had spent his entire career up until that point with the British Indian Army, and was described by one of his colleagues as a ‘Pocket Napoleon’. However, by 25 August he felt the Boundary Force was fatigued and their mood explosive. The British officers, he said, had done their best and the situation was beyond salvation. The force was disbanded just two weeks after partition, and had been active a mere thirty-two days. The two new dominions took responsibility for the security of refugees on their respective sides of the border. By 1948 all the British military units had left.

‘I think we all, sort of people like myself and other British officers, felt that partition was a huge mistake, but I think we also felt that the whole thing was too quick,’ says Denys. ‘It was speeded through. They should have taken a bit more time. The whole thing was not thought through. I think the British government of the day were anxious to get it done quickly and Mountbatten was a pretty ruthless man. And he backed that and made sure it did go through quickly. And it was a great mistake. If everybody had taken another six months or so, a lot more could have been sorted out. That’s my – that was the view we all held.’

Denys returned to the ‘dreary’ port of Liverpool, demobbed, with a longing for India, and no idea what to do with the rest of his life. He spent most of his £50 war gratuity on going to the 1948 Summer Olympics in Wembley every day. It was four guineas a day to enter: ‘It was the best money I ever spent.’ Yet all he wanted to do was return to India. His dear friend George from his regiment suggested a job at a tea plantation, and so in 1949 Denys returned to India, and spent the next twenty-five years in Assam.

Denys is ninety-two when we meet, a very sprightly ninety-two. He lives in Dorset, in a picture-perfect English cottage. It is touching to hear of his deep affection for India, the place he spent his formative years, where he saw active service, made his career, met his wife Elizabeth and raised their four children. The only time he gets to try out his Urdu and Hindi now is when he is speaking to an operator at an Indian call centre, to complain that his broadband is not working. Denys is a vanishing generation, an old-school British gentleman. If you passed him on the street you would not know part of him belongs to a foreign land, a land he still holds dear. ‘India means a lot. I would love to go back, actually, I’m getting too old to do it now. I have a great sort of feeling for India.’

Denys Wild OBE was born in 1925 in Addiscombe, Surrey. He served as a captain with the British Indian Army during the Second World War. From 1949 he worked in tea plantations in Assam, becoming a general manager. On his return to the UK in the 1970s he worked in the Foreign Office, specialising in Indian affairs. He was awarded an OBE for his work as chair of the Assam Branch of UK Citizens Association and for helping evacuate UK citizens during the secession of East Pakistan from Pakistan in 1971. He died in July 2018, aged ninety-three.

PARTITION VOICES

UNTOLD BRITISH STORIES

Author: Kavita Puri

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Pages: 320; price: Rs499