There is nothing unusual about gesturing while talking or using fingers to tear a sheet of paper. But when Manu T.R. does it, it is a step forward for medicine in general and transplantation medicine in particular. Manu's are the first pair of hands to be transplanted just above the wrist in India.

The man from Thodupuzha, Kerala, underwent double hand transplantation at Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences in Kochi in January last year. Words may fail to describe his agony after he lost his hands in a train accident a few years ago. Coming to terms with a new set of hands was not easy either, but he did not want sympathy. His straight posture exudes a confidence he has gained over the last one and a half years. Manu, 32, now works as counselling assistant at the hospital. Who better to motivate those in pain than someone who has suffered loss and found new life?

Manu as recipient of a cadaver organ has had to wrestle with haunting doubts about the supernatural. "The hands belonged to Benoy," says Manu, recounting those painful times and how he banished the demons. "But after he died, his body belonged to his mother. And his mother has willingly given the hands to me. So now these are mine."

Saji with occupational therapist Arun N. Nair | Sanjoy Ghosh

Saji with occupational therapist Arun N. Nair | Sanjoy Ghosh

Jith Kumar Saji, too, had similar anxieties, says Manu. Twenty-one-year-old Jith of Iritty near Kannur, Kerala, lost his arms below the elbow after he sustained electric burns three years ago. Life came to a standstill and he stopped going to school. News of Manu's new hands gave hope to Jith's family. They came to AIMS and he was registered with the Kerala Network for Organ Sharing after several rounds of counselling.

"Before a patient is registered for transplantation, they go through several rounds of discussions with doctors and counsellors. Because patient motivation is important," says Dr Subramania Iyer, head of the centre for plastic and reconstructive surgery at AIMS, who led the team that conducted the transplantation. "They should have enough motivation to work on their hands for a year or two following the transplantation. They also need to know that they will be on immunosuppressants lifelong. There should be social support, too."

Meanwhile, another double hand transplantation took place at the hospital in April. The recipient was Abdul Rahim from Afghanistan.

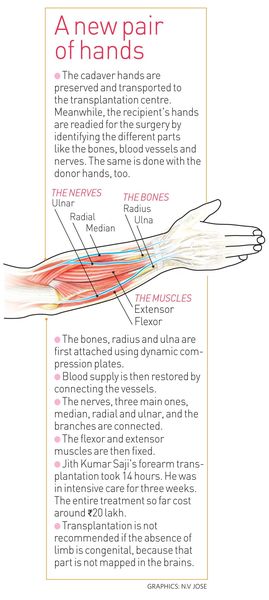

Jith's wait for almost a year for donor hands ended on May 23 when Raison Sunny was declared brain dead at Little Flower Hospital in Angamaly after an accident. Within hours, Jith underwent a double forearm transplantation, the first in the country, at AIMS.

"The current one [double hand transplantation] is the first from the forearm level and this has not been done much around the world also," says Iyer. Even double hand transplantation like Manu's is not common; only about 50 people have received new hands at the wrist level globally.

Manu T.R. plays jenga, which is used in rehab, with a patient at the hospital | Sanjoy Ghosh

Manu T.R. plays jenga, which is used in rehab, with a patient at the hospital | Sanjoy Ghosh

Iyer says that AIMS has received around 200 hand transplantation requests so far, including requests for transplantation of single hands and fingers. "The hospital is not considering single hand transplantation at the moment," he says.

For one, the patient would be required to take immunosuppressants all life even if the transplantation is of a single hand. Most people with a missing hand somehow get on with life independently, unlike people who have lost both hands. "The principle of transplantation is, if you have alternate methods of reconstruction available, those should be preferred," says Iyer.

In hand transplantation, besides checking the blood group and antibodies to minimise chances of rejection, the size is matched. Because of this reason, a donor of the same gender is preferred. "Less than 10 per cent mismatch is best acceptable," says Iyer. "That happened in Jith's case."

Once the donor is identified, the next challenge is to ensure the hands reach the recipient in time without damage. "The muscle mass from Raison's hand can change with time because of lack of blood supply," says Iyer. "At wrist level, since there are no big muscles, they withstand the lack of blood supply longer. Because of muscle mass, the forearm does not withstand the lack of blood supply for long. So we have to be quicker. If a wrist can withstand for six to eight hours, it is four to six hours in forearm transplantation." Manu's and Rahim's donors were at AIMS only.

The success of a hand transplantation surgery depends a lot on rehabilitation. "They have to work under supervision for at least a year to regain movements. Manu worked for more than a year, Abdul worked for a year, Jith will need to work more because of all the muscles," says Iyer.

"Jith's muscles will start working only when they are innervated," says Dr Mohit Sharma, clinical professor, centre for plastic and reconstructive surgery at AIMS and part of Jith's hand transplantation team. "It may take three to five months before even small flickering movements start." When the transplantation is closer to the wrist, the fingers start moving within 10 days.

"In Manu's case, sensation was achieved in about nine months," says Iyer. "In Jith's case the same may take about one and a half years. And the full sensory function may not be as brilliant as in Manu's case."

Jith's exercises in the Occupational Therapy and Virtual Rehab room include playing tennis on Xbox. Does he like it? This is the only relief, Jith smiles shyly. Standing in front of the camera, all he has to do is swing his arms to tackle the serves.

"This is also used for patients with spinal cord and brain injuries," says Dr Ravi Sankaran, clinical assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at AIMS. He then moves his shoulders and head sideways to show what the patients do to make the player on the screen swing the racket.

"Until we get muscle power we have to keep the tissue supple, which means flexing, stretching, mobilising," explains Sankaran. "Since he has no actual hand function we have been using video games. This makes the brain perceive the hands which is always the first step. When Jith finally gets some hand function then we can start strengthening." After the nerves reach the muscles, their contraction through electrical stimulation of the hand provides a feedback to the brain.

In a video on Sankaran's computer, Manu is seen doing commonplace activities like unscrewing the cap of a bottle and pouring water from a bottle as part of his rehab. To restore sensory function, objects with a rough surface like sandpaper are used, informs Jith's occupational therapist Arun N. Nair.

The rehab room is alive with light banter and the camaraderie between Manu and Jith is evident. Outside, Manu instinctively pulls up the sleeves of his kurta to push a wheelchair.

Later he helps Jith with the buttons of his full-sleeve shirt, which he wears over one with short sleeves. He then ties Jith's surgical mask, slowly and patiently but tying it nevertheless.