IN THE WOMB of adversity lie the seeds of resurrection. This is the only hope for Boris Johnson after he suffered a string of defeats in the very first week he faced parliament as prime minister. “Take back control” is the rallying cry of Brexiteers who want Britain to leave the European Union. But Brexit champion Johnson lost control of parliament, the nation’s decision-making process and the Brexit agenda. “He has no authority, no majority, no morality,” said opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn of the Labour, who appears to have outwitted the prime minister for now.

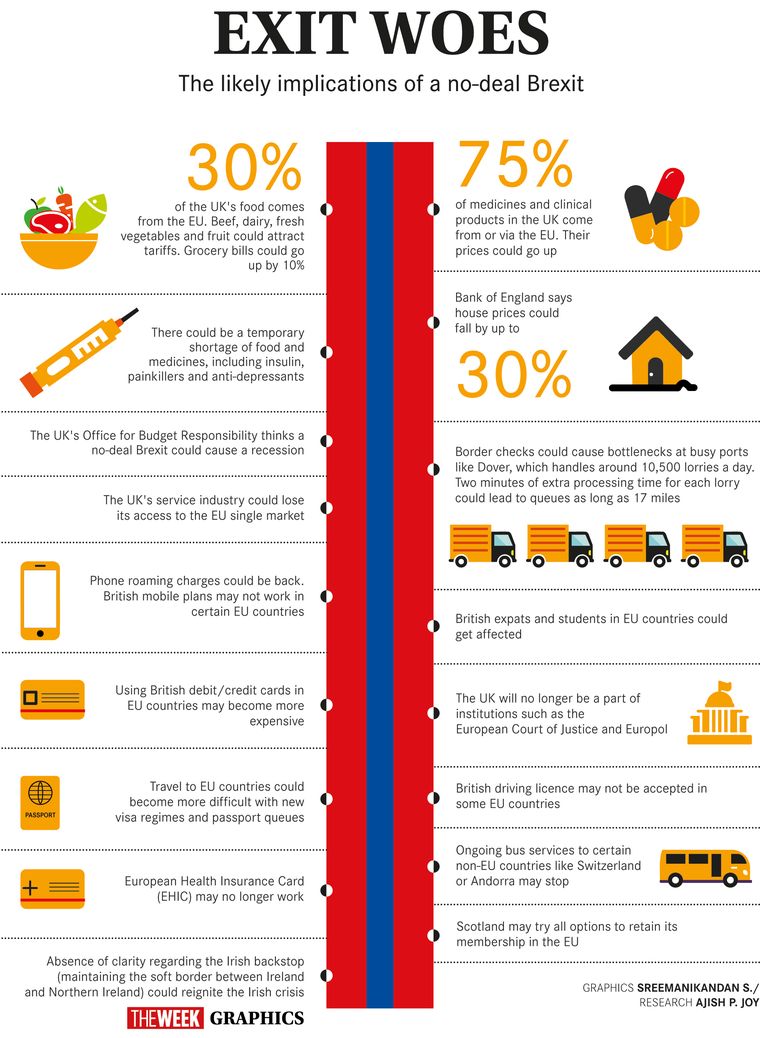

Johnson underestimated the fierce resistance to his “do or die” war cry to take Britain out of the EU by October 31, “with or without a deal”. Many Britishers believe that a no-deal Brexit is “reckless, irresponsible and unconscionable” because of the predicted disruptions, chaos and food and medicine shortages. Said Stephen Phipson, CEO of manufacturers’ organisation Make UK, “Investment is grinding to a halt. We need an orderly Brexit. We need a deal with the EU.”

That sentiment sparked resignations and stunning defections in Johnson’s own Conservative Party, enabling parliament to outlaw no-deal Brexit. Sacrificing their long, distinguished careers, 21 Tory MPs defied Johnson, choosing “country over party”. The illustrious list includes Philip Hammond, who was finance minister till two months ago, Winston Churchill’s grandson Nicholas Soames and Kenneth Clarke, currently the “Father of the House” who entered parliament almost 50 years ago, when Johnson was just six.

The “Greek twist,” reminiscent of classical drama, was his younger brother Jo Johnson, minister and MP, resigning in protest against a no-deal Brexit saying he was “torn between family loyalty and national interest”. People wondered: “How can we support Boris when even his brother does not”. Lord Richard Newby, leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords, said, “Jo leaving is a grim and damaging blow. Boris has lost his majority in parliament. He has lost all six votes. He does not have majority even in his own family.”

Though he himself had defied party whip on Brexit votes when Theresa May was prime minister, Johnson expelled the rebels, denying them a Tory ticket in future elections. Scottish Prime Minister Nicola Sturgeon called Johnson “a tin-pot dictator” for prematurely proroguing parliament, sacking dissenting officials and for punishing party leaders.

Expelled former minister Rory Stewart said Johnson was panicking. “Taking on parliament is not the way to deliver Brexit,” he said. Johnson also faces a welter of law suits, including the one filed against him by former Tory prime minister John Major.

Experts agree that Johnson and his backroom boys miscalculated, mainly because his team is full of hard-core Brexiteers and lobbyists lacking parliamentary experience. They did not expect the rebels to forfeit their parliamentary careers. In the crosshairs of condemnation is Johnson’s chief strategist, Dominic Cummings, seen as a shadowy, sinister Machiavelli, the “Rottweiler of 10 Downing street”. He was chief Brexit campaigner in 2016. But governing is not campaigning and parliament cannot be “managed” through social media and data analytics.

Johnson’s “messaging” failed to impress parliamentarians because they do not trust him. Detractors accuse Johnson of “lying” on important issues and using EU negotiations as a fig leaf to conceal his real intention of triggering a no-deal Brexit. EU negotiators said they were yet to see Johnson’s proposals and charged Britain with not acting in good faith. Corbyn said Johnson’s Brexit proposal was “cloaked in mystery like the emperor’s new clothes”. After parliament asked Johnson to delay Brexit till January 31 in the absence of a deal, the prime minister responded that he would “rather die in a ditch”.

But he would rather live at the stumps. Though risky, a snap election that capitalises on Brexit fatigue is Johnson’s escape hatch. People are so sick of Brexit that they just want it out of the way and get on with their lives. But the Conservative Party is in a meltdown. Progressives are purged and tribes are warring. It is becoming a right-wing Brexit party, “shrunken to an English nationalist rump”, editorialised the Financial Times. Johnson’s attempts to force a snap election, however, have so far been rebuffed by parliament.

Brexit was always a “Middle England project,” championed by non-urban, insular, middle and lower class, conservative inhabitants in the British midlands and southern countryside who could not care less about Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Their worldview is powered by colonial nostalgia, English pride and aversion to foreigners. “We paddled alone for 1,000 years. We can paddle along for another 1,000 years,” is their motto. Johnson is their hero.

But the swell of uniting adversaries who see Johnson as a villain aggravates his adversity. “Break Brexit Boris,” said Welsh parliamentarian Liz Saville-Roberts. “We have an opportunity to take down Boris and we should take that.” Leading the charge is the re-energised Corbyn. His Labour Party did well in the 2017 elections, drawing support from people crushed by austerity programmes imposed after the financial crisis.

But Corbyn is a polarising, controversial figure. He is vilified as a “Commie relic” for his radical economic policies that favour tenants over landlords, workers over owners, taxing the rich, nationalising public utilities and redistributing income, assets, ownership and power from the elite to the masses. Johnson has cleverly fuelled capitalist Britain’s allergy to socialists by demonising Corbyn. The Johnson-Corbyn battle is seen as the match between “Lefty crank and Righty clown”.

Corbyn’s Achilles heel is his vague Brexit policy. His evasive answers have been more slippery than the Loch Ness monster, now presumed to be a giant eel. He is hamstrung because his party is split, mirroring the country. Recent opinion polls show that 44 per cent of voters oppose no-deal Brexit, while 38 per cent support it.

Labour’s confusion over Brexit has hugely benefitted the Liberal Democrats who emphatically want to remain in the EU. Said party supporter Alastair Campbell, “In the 1970s, Britain was the sick man of Europe with markets only in poor, far-flung colonies. Joining the EU was the best thing for our economy.” Also altering the political landscape is the rise of Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party that won the highest number of votes in the European parliament elections held in May. One crucial question is whether Farage will collaborate with Johnson to prevent splitting their common vote bank.

Johnson has been “cash-bombing” districts to keep vote banks happy, promising giant infrastructure projects like high-speed rail, motorways and bridges to transform “Left Behind” England. He borrows a leaf from Augustus Caesar who supposedly said on his deathbed: “I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.” But Johnson’s building history so far is not exactly Augustan. As mayor of London, his expensive “vanity projects” included overheated, overpriced buses, seldom used cable cars and the “Boris Island” airport project that failed to take off. Just like his Brexit proposals.

Critics wonder whether Johnson really wants a deal or if he is fundamentally averse to the EU like US President Donald Trump. Johnson seems to be going by the Trump playbook: courting his base, treating policy like war, going at it with all guns blazing. But in Britain, neither this strategy nor the tactics appear to be working. Unlike Republicans in the US, senior Tories stood up to Johnson and unlike the US Congress, Westminster cornered him. British parliamentarians see Eton-educated Johnson’s self-inflicted drama as dormitory escapades and schoolboy theatre, with Clarke chiding him, “Stop treating Brexit as a game.”

Trump’s controversial national security adviser John Bolton called on Johnson last month with a promise to start trade negotiations from November 1—literally the morning after the Brexit deadline. But Britain’s fate on that day is still uncertain. Parliament has banned no-deal Brexit. So will Johnson resign, break the law or break his promise? Will it be a new deal or another delay? Johnson is in office, but not in power. Governing without a majority presents an inevitable denouement—elections. Johnson could go down in history as the shortest serving prime minister. Brexit could topple Britain’s third leader in a row.

In the womb of adversity also lie the seeds of destruction. Rejuvenation or disintegration—these are the two sides of the Brexit coin. As it is for Britain, so it is for Johnson.