It is funny—the one thing that you do not expect from a Pankaj Mishra book, especially as it distills into fiction his writing as a critic of globalisation and capitalism. But his new novel Run and Hide—in which he returns to fiction after 20 years—is surprisingly (at least in parts) humorous. A word that Mishra is resolutely not. He is known for his eloquence. His measured (never flippant) responses. And his unflinching chronicling of the darker side of globalisation.

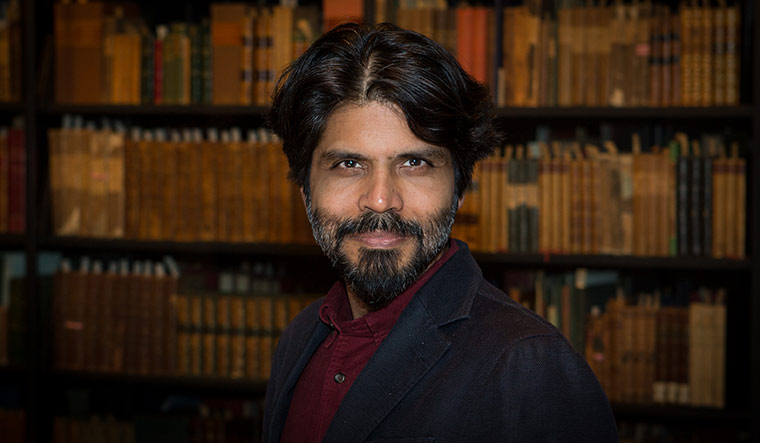

“I really wanted it to be a funny book,” says Mishra from London, over Zoom. “I am glad you spotted that.” It is the only time there is a hint of levity in the conversation. It is around 8am, and there is an issue with the camera of his laptop. His voice, however, booms across the continent, assured and articulate.

Mishra began writing fiction as a commerce graduate at the age of 17. With the dream of becoming a novelist, he sent a few pages of a novel he wrote to a publisher. They wanted more. But in 1980s India, when the Indian novelist did not exist, Mishra never pursued it. The Romantics was his later foray into fiction in 1999. “Writing non-fiction became a way of being in the world of making a living,” he says. “It was only a matter of time before I came back to fiction. I am surprised it took me so long, because in the end, creatively, writing fiction is the most fulfilling thing I can do. In other words, exploring the inner lives of people, their motivations, the things they say....”

Mishra does exactly this—take a deep dive into the inner worlds of his characters, poster boys of the India Shining story. Run and Hide is a book for contemporary times. On the surface, it is the story of three boys—Arun Dwivedi, Virendra Das and Aseem Thakur—who get into IIT, the dream that has come to symbolise the aspirations of new India and its potential to finally open the doors to success. It follows their lives, their choices and their careers, but goes deeper into the themes of ambition, greed, the system, morality, change, and the seductive and destructive aspects of an economy based on individualism and consumption.

The narrator, Arun, has more than a passing resemblance to Mishra. He lives in a small hill town like Mishra, resolutely refusing to be part of the “economy of social media” and remaining focused on work. The morally dubious Aseem, a hustler editor facing rape allegations, is easy to identify. Scattered through the pages are others—familiar and spottable. Alia— whom Arun, at 50, falls in love with—is a privileged Muslim elite battling trolls on social media who is writing a book on the three. It is very much Alia who is the catalyst for the story. “People have said this—all these characters are composite. I think the closer the reader is to the society that the novelist is writing about, the stronger the resemblance will be seen,” says Mishra. “But at the same time, I wanted to have the creative license. A lot of people share those characteristics—ambition, pushiness and the vulnerability to being corrupted and becoming more and more infatuated by fame and wealth.”

At its heart, the book tackles the dangers of the compromises one makes on the road to success. “It is only in retrospect that I can see the danger Aseem never reckoned with: that in our attempts to remake ourselves, to become ‘real men’ simply by pursuing our strongest desires and impulses, with no guidance from family, religion or philosophy, our self-awareness would narrow, the distortions in our characters would go unnoticed, until the day we awaken with horror to the people we had become,” writes Arun.

Mishra uses the vehicle of fiction to explore the theme he has spent his life chronicling—the ruthlessness of liberalisation. It is deeply political, dark, unflinching in its criticism, insightful, vividly imagined and, as always, troubling.

From Butter Chicken in Ludhiana—his travel book written in the 1990s which captures a changing country—Mishra has focused on the transformation of the country as it hurtles towards modernisation, shedding its past to embrace the more shiny. Unlike his non-fiction—sensitive, percipient, and holding up a mirror to the uglier side of the story—Mishra’s fiction focuses on the great price that progress in the current economic model brings. It is also a book that is keenly felt. There are parallels with Mishra’s life that go beyond just the obvious. There is, for example, Arun’s attempt to run away and seek shelter in spirituality. It is a theme that Mishra, too, has explored with Buddhism.

If Mishra is the voice of doom in his non-fiction, in his fiction, his anguish is palpable. While his arguments are forceful in his essays, in his fiction they are more powerful and hard-hitting. And offers a brief glimpse of why Mishra is compelled to stick to a critical voice, not only by his politics and ideology, but also something deeper—loss. “In the end, you can use a number of big words to describe what is happening in India, whether it is globalisation or liberalisation,” he says. “But what has happened in India is unprecedented. The modern world begins with uprootedness on a large scale. In the Indian experience it is very difficult to go back. When you are leaving home, it is something irrevocable. You are closing a chapter of your existence that will never be opened again. I see this personally in my own life. I go to places in Delhi I knew. I go to Varanasi or Banaras, and notice how they have been utterly transformed that I can barely recognise them. The places that held my most cherished memories are now gone, so those memories really only exist in my head. There is nothing out there that corresponds.”

For Mishra, who left home as an adult to move across the world, it is a slipping away that is harder to bear. “We all have to cope in our own ways—which is to read, think, write, create and remember,” he says. “Remember that is very important. Keep in touch with our friends and that is how we do it. I am further removed from the places I grew up in, which formed a part of my early years. I have to make a deliberate effort to keep in touch. Otherwise you feel that you are drifting through the world, further and further away from the things that made you.”

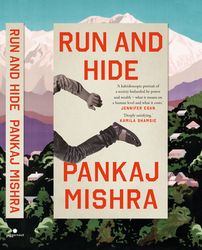

Run and Hide

By Pankaj Mishra

Published by Juggernaut

Price Rs599; pages 327