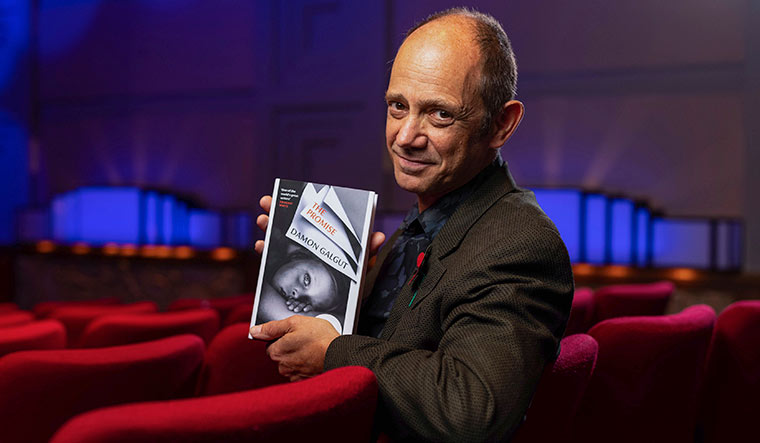

With Damon Galgut being awarded the Booker Prize on November 3, Africa is once again the focus of international literary attention. Abdulrazak Gurnah had won the 2021 Nobel Prize for his novels highlighting the problems in his East African homeland, Tanzania. But, South Africa, which went through the harrowing experience of apartheid, differs vastly from East Africa. And Galgut, whose two previous novels—The Good Doctor and In a Strange Room—were short-listed for the Booker, has brilliantly evoked the complex problems of his country in The Promise.

The story, set in Pretoria, begins in 1986—when apartheid was slowly drifting towards an end. But the residual effects of the abhorred system are still felt in the novel. The eponymous promise occurs on page number 19:

“Do you promise me, Manie?”

Holding on to him, skeleton hands grabbing, like in a horror film.

“Ja, I’ll do it.”

“Because I really want her to have something. After everything she’s done.”

“I understand,” he says.

“Promise me you’ll do it. Say the words.”

“I promise,”

Pa says, choked-sounding.

Manie is the head of the family. His wife, Rachel, is in her death throes; she extracts a promise that a small house her black maid has been occupying would go to her as a reward for her selfless devotion to their family. Of course, Manie could make short shrift of this unwritten promise, but the youngest of his offspring, 13-year-old Amor, was a witness. Like her mother, she sympathises with the maid, Salome, who had also nursed Rachel. Amor feels that the promise should be honoured at any cost.

After Rachel’s death, Manie and their other children—Anton and married daughter Astrid—refuse to commit to the issue. Manie goes to the extent of denying the promise. Disgusted, Amor distances herself and, later, trains to be a nurse in the HIV section of a Durban hospital.

Meanwhile, her family disintegrates. Manie dies, after being bitten by a cobra. An adulterous Astrid is murdered. Anton—plagued by guilt, for acts committed as a conscript—kills himself with the family shotgun.

Finally, after 30 years, when middle-aged Amor is in a position to fulfil the promise, there is an unexpected turn of events. Apartheid has become a thing of the past and the black, who previously had no right to own landed property, are eager to assert their dignity. The final confrontation between Amor, Salome, and her son, Lukas, demonstrates this:

“It isn’t much,” she (Amor) says. “I know that. Three rooms and a broken roof. On a tough piece of land. Yes. But for the first time, it’ll belong to your mother... That isn’t nothing.”

“Yes,” Salome agrees, speaking Setswana. “It isn’t nothing.”

“It is nothing,” Lukas says. Smiling again, in that cold, furious way. “It’s what you don’t need any more, it’s what you don’t mind throwing away. Your leftovers. That’s what you’re giving my mother, thirty years too late. As good as nothing.”

Despite Amor’s sustained efforts, the promise could not be kept.

From the literary point of view, The Promise is a well-crafted novel with four almost equal parts, each focusing on the death of a member of Amor’s family. Manie dies in the second part, set in the late 1990s; Astrid in the third (set in 2004) and Anton in the fourth (2018). A mythical/ethical interpretation is possible—an unfulfilled promise is bound to have grave consequences. From the unexpected deaths, it looks as though a curse had befallen the family because of a promise not honoured.

But, the word promise in the title seems to have broader political connotations. Any new political set up which promises happiness and wealth to the people will fail when corruption and moral bankruptcy find their way into day-to-day affairs.

All in all, while his two illustrious predecessors—Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee—had dwelt on the political and social complexities during apartheid, Galgut steers clear of them. He concentrates on the equally troubled post-apartheid period, endowing his novel with qualities that lead to a multi-layered interpretation. There, indeed, lies his originality.

Kichenamourty is former dean, School of Humanities, Pondicherry University

The Promise

By Damon Galgut

Published by Chatto & Windus

Pages 304, Price Rs699